Livestrong

The Lance Armstrong Foundation is not on the toney west side of Austin. I left my hotel for a 9am meeting with the Foundation's CEO, Doug Ulman, and at 8am I Google-mapped Starbucks in downtown Austin. Ping, ping, ping, a half-dozen red dots appeared on my iPhone. But, nothing at all within miles of the Foundation's headquarters, and nothing east of Highway 35—a firm line separating chic and fashionable downtown Austin from several square miles of one-story Hispanic.

I took a tour of the Livestrong digs and it's impressive—not because what it cost, but for what it didn't cost. The building was formerly a paper distribution center. To ready Livestrong's headquarters for action, half the roof was torn down and replaced with rows of skylights, so that workers could enjoy natural light. The beefy glue-lam beams that held up the roof were retasked as framing wood for the interior build-out, such as the free-standing offices.

These offices feature a lot of glass, because transparency is a theme that runs through the organization. You'll have to look hard to find an office with a closed door.

Many or most of the 80 or 90 employees are cancer survivors—I asked each person I met—including CEO Doug Ulman, a three-time winner over cancer.

Why here? While this organization is routinely listed among Best Places to Work by Outside Magazine and The NonProfit Times, why would its management stick this corporation in a place where the employees have no hope of a nearby Panera, or anything like it, and are probably going to have to paper sack their lunches? A line, spoken from Jeremiah Johnson, where Del Gue quotes his mother, came to mind: Make your life go here, son. Here's where the people is.

The Foundation sits in the Hispanic quarter of Austin because here's where the people is. Here's where the need is.

And what is the need?

It's about reducing the stigma of cancer, according to Ulman; helping people navigate their ways through available clinical trials, medical bills, and doctors who were naïve to the latest information on particular cancers. It's about connecting people who have cancer to the care and the services they need.

Okay. But pretty ethereal. Hard to measure outcomes, or efficacy. We're unanimous in this, aren't we? A charity is best judged by how much of its money flows straight to physical, palpable good. If I give money to the Red Cross I want to see bags of blood in Haiti that my money bought. Most of us are skeptical of intangible missions that promote education or awareness.

Nevertheless I listened as the mission, and its execution, was explained to me, as I sat through tours and interviews hosted by Livestrong's staff.

But I was distracted by somebody who was visiting the Foundation at the same time I was, who I wanted to meet. Those of us who knew and were close to Armstrong in his triathlon days followed the news of his downward spiral. Testicular cancer. Metastasis. In his lungs. In his brain. We were waiting for Lance to die.

Who's Lance's Hero?

Everybody has heroes. There is someone Brad Pitt, Barack Obama and David Beckham all badly want to meet. I don't know who that person is in each case, just, no matter who you admire or idolize, that person has his own mentor, hero, target of admiration. Who's Lance's?

One candidate may be the man with whom he made contact, when he was near his lowest—a specialist in his rather rare form of cancer: Dr. Craig Nichols, then working and residing in Indiana. Armstrong made the pilgrimage, and the big ship that was Armstrong's cancer slowly started to turn.

He and colleagues were visiting the Foundation at the same time I was, as Livestrong programs parallel some of their own interests. Dr. Nichols is also on Livestrong's Board of Directors.

I met Dr. Nichols, and then spent an hour-and-a-half talking to him and his wife, in the Foundation's foyer. Hearing him express his own challenges brought home what those who work at the Foundation were trying to tell me. The problem, according to Dr. Nichols, is the inability of any general oncologist to stay abreast of the protocols in every cancer that yield the best outcomes. Armstrong was floundering in his own treatment because he and his Austin-based oncologists were not plugged into testicular cancer best practices.

What Do They Call the Man Who Finishes Last…?

The delta in outcomes for something uncommonly seen by oncologists, like cancer of the testis, may be 30 points, that is, if general oncologists had access to the best data, then Dr. Nichols believes that successful treatment—high quality lives lasting 40 years and more post-cancer—would raise from 70-ish percent to near 100 percent. Dr. Nichols maintains that cancer of the testis is, as cancers go, an easily treatable disease, if knowledge and behavior is optimized, starting from the patient, continuing along the chain of care. That's important when you're talking about a cancer striking males who are, on average, around age-25 when they contract it.

I was listening on NPR, several weeks ago, to a doctor working on public health's front lines, and this was during the Susan G. Komen fracas. She voiced an astounding statement: When her office sends notices to their patients of potentially troublesome pap smear results, about three in ten patients do not respond or return. They just never come back. As I spoke to the doctors I met at the Foundation, I was told story after story that spoke to stigma or shame or denial. Very treatable cancers. But, families who did not have historic access to medical care saw their loved ones die; did not therefore trust that cures were available; so repeated the cycle of not seeking care for themselves, their spouses, their children.

It did not occur to me that a mission centered around information and navigation had much heft to it. Nevertheless, it's undeniable that the very quickest way to increase high-quality survival rates is to appeal, constrain, argue, educate—to bring a patient to care; and then empower his or her doctor with knowledge and resources.

Accordingly, the unsexy jobs of digitizing medical records; of grabbing keyword search technologies that cause us all to see the ads "appropriate" to us, leveraging such technologies to cause a doctor to "see" therapies appropriate to rare cancers; multi-level marketing patient best practices through the finding and training of volunteer ambassadors who'll empower and enlighten those with the least access to best practices; these are the most efficient ways to increase outcomes immediately.

What do they call the least mentally equipped guy in a F.I.S.T. Workshop? Certified. This is a variation on a morbid joke that ends with the words, "doctor," or "esquire," and it sure seems to me that the businesses of doctoring and lawyering mirror that of bike fitting. Contemplating the delta that exists between good doctoring and average (or worse)—through the prism of the delta between good bike fitters and bad—is terrifying. Still, as I contemplate my own experiences with the medical community, it explains a lot.

There is a liberating aspect to this, when you realize you can inject your own energy into how you interface with the medical community. My wife and I, for example, often step into the "patient advocate" roles in our respective families. I thought I was the terror of the medical community… until I saw my wife in action. Because hospitals are not like restaurants, and you're not likely to get spit in your soup as a result of your complaints, the bottom-up approach to getting the care you or your loved one needs is not just a luxury, but an imperative.

This is, in broad strokes, the approach championed by Dr. Nichols, though he might not put it the way I just did. There are two prongs to his program. First, appeal to the "end user," as we say in the bike biz. The "end user" in Dr. Nichols' case is the cancer-encumbered patient. Not every patient has the wherewithal to do what Armstrong did: fly himself to one of the four testis-specific cancer centers around the country. Dr. Nichols advocates for the next best thing: Bring the knowledge of the cancer center to the doctor.

But, just as in bike fit, the doctor must sometimes be prodded into action by a patient who has just enough information to generate a spark. "The internet is the mediocre doctor's worst nightmare," it is said.

But Dr. Nichols' interest is not in making life miserable for his colleagues, rather, it is just not possible—he says—for even an oncologist to stay current on what's most efficacious for cancers he might see once a year. Would you trust a general bike fitter to fit you, if you're his one tri bike fit that year? So, the second prong of his outreach is to maintain an informational database, and match the information on testis cancer to the oncologist who needs it, at the time he needs it.

It's a higher-tech, and more hands-on, version of the databases we maintain here on Slowtwitch, matching those who need a coach, a bike shop, a fitter, a tri club, a race, to an athlete who has no idea what services are out there. Just, Dr. Nichols' mission has more urgency attached to it.

A Little Education Goes a Long Way

Dr. Nichols mission largely parallels that of the Lance Armstrong Foundation. The therapies are there. The protocols are there. The knowledge is there. There's just gum in the works. Even in the richest nation on earth. Even with the most expensive per-patient care in the world. There's gum in the works, and that gum is the lack of information and education.

If you parse the Foundation's financials, you'll find that it spends about 7 or 8 percent of its fundraising totals on administration. Another 12 percent goes to fundraising, which means $4 out of every $5 dollars go to programs, the point of which are not to fund cancer research, rather to grease the skids, and mate cancer patients to fruit of that research. And, to help them with all the tangential challenges: navigating the bills, managing life while undergoing cancer treatment, and the like.

Just under 20 percent of the money Livestrong invests into programs goes to legislative advocacy. This is a variable number, and has recently been as much as double this percentage. I would imagine that this ebbs and flows based on election years, or specific legislative or statutory projects.

About $4 out of every $10 that goes to programs goes to home-grown, endemic, Livestrong-developed, programs. Another $4 out of $10 is paid out in grants to organizations that can administer a program better than Livestrong could.

For example, Livestrong partners with the Patient Advocate Foundation (PAF) which, simply put, provides the same services to families that my wife and I provide for our families. Except the PAF are experts.

EmergingMed, another Livestrong partner, is an organization that matches people with clinical trials.

Imerman Angels provides one-on-one support for cancer survivors and caregivers.

One of Livestrong's missions is to serve as a clearinghouse, putting people in touch with organizations like the three above. It reckons it personally imports into its individualized navigational services about 12,000 cancer patients, or their caregivers, annually.

Livestrong has deeply penetrated the Hispanic community. Its Promotores program has trained community leaders to, in turn, train Promotores in each of more than 30 cities. These are the fighters on the front lines who, intuitively, seem the best-equipped to draw a straight line between those that have, or might contract, cancer and the services available to them.

Livestrong has outreach programs to several African countries, most notably South Africa. This is an example of the fortunate nexus between Armstrong the athlete and the cancer fight advocate. His visit to South Africa in March of 2010 was an occasion both to compete in a pro bike race, and for the launch of Livestrong's Global Cancer Campaign in that country. Africa's countries share a problem common to third-world and emerging countries worldwide: the stigma attached to diseases that are historically considered unbeatable.

But in this country, the admirable penetration of the Foundation into the Hispanic community—about 23 percent of all Livestrong's 12,000 one-on-one "touches" is to Hispanics—is not matched by a deep encroachment into America's Black community. The incidence of cancer, and its bad outcomes, disproportionately affects the Black population. And, Blacks are precisely those who could be best served by plugging into Livestrong's resources. To me, 6 percent seems low by a large amount.

Sports-Based Fundraising

If you've been a Leukemia Team in Training member, you understand the paradigm. Two years ago Livestrong was not in the top-20 in terms of dollars raised through mass participation sports. Now, they're sitting about fifth among U.S. non-profits. With Armstrong's deal with World Triathlon Corporation, lord only knows what the fundraising amount will look like for 2012.

Leveraging the triathlon community—especially the Ironman community—is a natural. By rough calc it seems to me $3 million in incremental funds ought to be raised straightaway through the WTC deal. But it could be the tip of the iceberg. How many incremental sign-ups into the sport could the Armstrong-triathlon nexus provide? I don't know and no one does.

One missed opportunity in this foundation's efforts is the lack of preparedness to accept and absorb incremental—especially the unathletic incremental—entrants into triathlon. It's axiomatic that newbies aren't participating in, and shouldn't enter, the races that WTC owns (with the possible exception of St. Anthony's Triathlon).

Yes, it's a missed opportunity, but, not every wave needs to be surfed. Livestrong is determined to stay nimble, and to remain in one office, no chapters, and to have fewer than 100 employees. So I don't know that Livestrong would ever be structurally able to leverage for fundraising the influx of tens or hundreds of thousands of newbie multisporters.

Still, triathlon might do itself a favor if it seized the opportunity to import Lance-admiring newbies into its ranks, but, this is easier said than done. The Foundation—by design—has no coaching infrastructure, nor any local presence, it has no chapters spread around the country (as TnT does). Triathletes as part of a Livestrong fund-raising project are neither encumbered by, nor aided by, a mandatory local team affiliation. Consequently, lone-ranger triathletes must by nature be self-sufficient and, probably, already part of our ranks. If the Lance Factor brings prospective triathletes into our sport, I see no vehicle for them to be Livestrong fund raisers.

My mission in business is to educate, instruct, empower, and connect. My mission in life is to learn, master, understand, to experience sublime moments, to protect those in my care, and then, when appropriate, pass on what I've learned.

It is ironic therefore that I did not understand or appreciate, at first blush, what Livestrong was trying to do—what it felt was most worthy of its money and attention. I took as axiomatic that cancer patients would routinely seek and receive care, and that cancer-appropriate therapies were more or less available across the board. Not so.

Maddeningly not so. Treatments for Armstrong's cancer could well have left him, if not dead, permanently brain or lung impaired. Instead, well, we know how the story has unfolded, thus far. Imagine those less able than Armstrong trying to steer and manage their own outcomes.

Typical of Livestrong's freestanding offices, lots of glass, built of repurposed beams holding up the roof of a paper distribution company.

You never know who you're going to run into. In this case, Livestrong's CEO Doug Ulman is entertaining WTC's CEO Andrew Messick and CMO Erik Vervloet.

This building is one of Austin's architectural treasures, not for what it is, but for what it isn't: expensive and gaudy.

You can build a Best Places to Work office out of a warehouse in the bad side of town, if you put your mind to it.

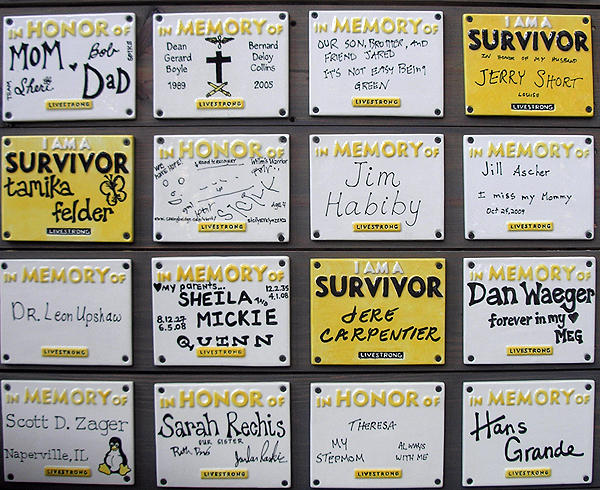

Livestrong employees are surrounded by the fruit of their work and the need to continue it.

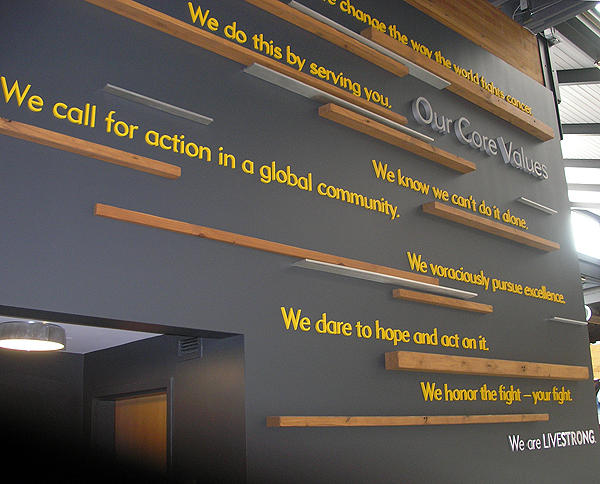

The building, the offices, the job, the organization, all strike a posture of transparency.

Half the roof of this building was torn out to make way for natural lighting. Beams like this provided the wood to build the offices.

What were ceiling beams are now benches in the cafeteria.

Unless you want authentic street tacos, you either eat here for lunch or you drive quite a distance.

Armstrong contemplated his own decisions in his personal fight with cancer while seated at this table, which is now in Livestrong's cafeteria.

Employees find reminders of the organization's purpose throughout the building.

One wants a bit of color: (Albert – Nathan Lane – in The Birdcage)

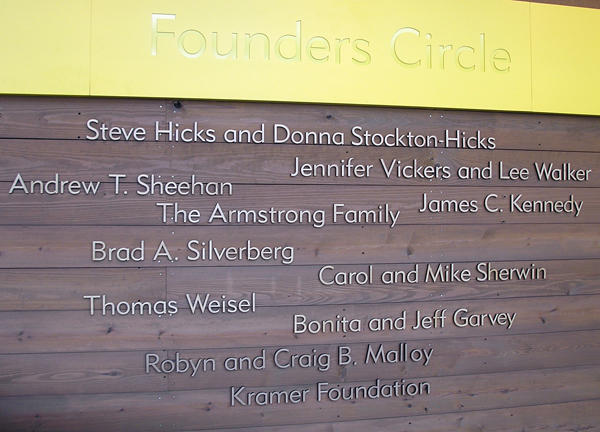

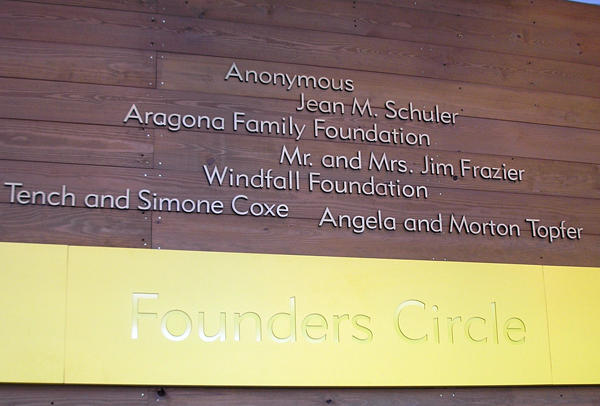

Founders gave money to start this foundation before Armstrong won his first TdF.

Founding members include Tom Weisel, a sponsor of Armstrong's going back to his Suburu Montgomery days.

The building features a lot of art, which is from Armstrong's personal collection. As I could find no Dogs Playing Poker on the walls, this was my favorite art piece in the building.

Dr. Craig Nichols and his gracious wife Ellen. Gents, assuming the situation calls for it, this is the one man on earth you want fondling your testicles.