Butterfingers!

Witnesses are sworn in and asked to identify the guilty party in a lineup of Olympic athletic catastrophes. Roll tape. One by one, they watch a series of mind boggling disasters.

The suspects are clearly athletes, futilely trying to exchange a small stick at high speed. The witnesses peer closely at this series of video clips and are asked to identify these hapless characters whose pratfalls most recall Buster

Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, the Three Stooges and

Chevy Chase as Gerald Ford.

As they watch and gasp, the witnesses’ first impressions of this parade of miscues are rich in similes.

A man suffering an epileptic seizure while hailing a cab.

The look of bug eyed terror on the face of the FBI agent played by Jodie Foster in Silence of the Lambs pursuing that psychotic killer in his pitch dark basement.

Demonstrators hit by riot control oleoresin capsules that make the ground too slick to stand.

Soldiers both struck by black ops, non-lethal, neuro-electromagnetic weapons designed to shut down the nervous system.

Many of the witnesses flash back to the final scene of Von Ryan’s Express where escaped prisoner of war Frank Sinatra is running to catch a train for Switzerland but is gunned down by a German machine gun inches short of vaulting into the caboose to freedom.

Others think the runners are afflicted by rapturous spasms, hallucinating that the innocent stick has turned into a venomous snake in a rural Pentecostal revival.

Finally the witnesses turn to one another. In a moment of epiphany, they all nod at what they are seeing.

“It’s the US Olympic 4×100 relay teams!”

US RELAY SPRINTERS LOOK COOL BUT ARE PITIFUL HELPLESS GIANTS

In their modern incarnation, US sprinters look so imposing. Sleek Oakley sport sunglasses carefully tinted for nighttime competition. Elegant, lightweight platinum and gold bling bouncing around the neck. Gold-tinted shoes for the biggest egos, shoes counterweighted for the curves like NACSAR suspensions, and microscopically engineered spikes that offer perfect traction. Razor cut sideburns, aerodynamic and aesthetically dynamic haircuts. Often, the faces look like action movie stars – macho with perfect bone structure. The muscles large, cut, ripped sleek. Their starts exude the coiled, focused energy of a rocket takeoff or the start line of a Top Fuel dragster. In full stride, they have the elegant extension of a cheetah or an antelope.

Backing each one of them is a support system equal to a Formula One race team. While each competitor seeking to become the fastest man or woman on the planet takes a slightly different approach, there can be a sprint coach, a start coach, a sports psychologist, a sports hypnotist, a nutritionist, a cook, a physiotherapist, a massage therapist, a manicurist, a hair cutter, an agent, a manager, a public relations firm and acting coaches for Olympic year ads, an entourage, workout partners, a baby sitter, an accountant, a kinesiology consultant with high-def, blu-ray, taping analysis of form, and, why not, access to wind tunnel testing for aerodynamic efficiency and body fat percentage. Not to mention the assets and resources of the USOC with its $600 million budget – a big chunk of which goes to track and field — for each Olympic quadrennial. And in the recent past, for the legions of confirmed and convicted cheaters, R&D investment in highly paid, illegal drug chemists and cooks like the BALCO lab.

All to shine in their four heats of 10 seconds every four year. And, oh yeah. For those curtain call bows, those afterthought processions their opponents call relays. They also have medals on the line – which American sprinters think of as their birthright.

LONG HISTORY OF US RELAY THRILLS — AND AGONY

After all, the US men won eight straight 4×100 relays from 1920 through 1956. Then they won 1964 through 1976, then 1984, 1992 and 2000. But their history of bungled relay handoffs – sometimes overcome, sometimes not — is equally rich. The US men crossed the line first, but were disqualified in the very first modern Olympic 4×100 meter relay in 1912. In 1960, US sprinter Ray Norton took off early and ran out of the zone and the favored team was disqualified. In 1988, the Calvin Smith-Lee McNeil exchange ran out of the zone and the US was disqualified. The list of mangled handoffs that were overcome is even longer. In 1964, poor baton passing put the US team fifth before Bullet Bob Hayes uncorked a 8.9-second anchor leg to save the day. In 1968, poor baton passing left the US men 5 yards behind, but world record holder Jim Hines ran the anchor leg and eked out a narrow win. In 2004, lousy passing didn’t result in a DQ, but left the heavily favored US men second to Great Britain by 1/100 of a second.

DÉJÀ VU ALL OVER AGAIN

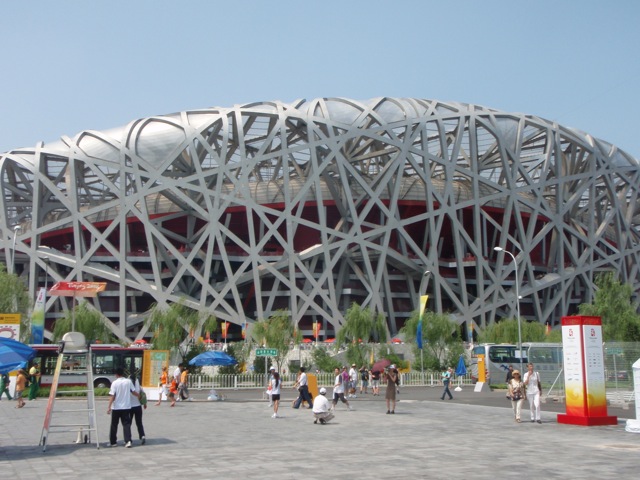

So it should not have been much of a surprise on August 22 at the Bird’s Nest that Darvis Patton’s arm could be seen wildly waving, desperately but unsuccessfully seeking to place the baton in contact with Tyson Gay’s equally frantic and randomly grasping hand in the 4×100 semis? Sadly, the US women seem to have caught the American men’s dropsy virus. Poor Lauryn Williams, who took off too soon for drug cheat Marion Jones to hand her the baton four years in Athens, found the Beijing Olympics were déjà vu all over again. There she was, looking for Torri Edwards to hand her the stick and grasping thin air once again in the 4×100 relay semifinals in Beijing.

STUNNED AND SHOCKED

Williams had the stunned reaction of a two-time lightning victim: "Maybe someone has a voodoo doll of me."

Williams was more in shock than Edwards, who screeched and looked like Edward Munch’s famous painting “The Scream.” She wailed on, speculating on even more occult conspiracy theories. "I'm telling people the stick had a mind of its own," Williams said. "It wasn't me. It wasn't Torri. It was electronic. It had a little bug inside of there. It jumped out. It wasn't either one of our faults.”

Both Gay and Patton attempted to take the blame. "I'm a veteran. I've never dropped a stick in my life," Gay said. "I take full blame for it.”

Patton disagreed. "It's my job to make sure he had it secure," Patton said. "So I take the blame for this."

New USA Track and Field President Doug Logan called for an investigation and a complete revamping of USATF relay training procedures. “When we drop the baton in back to back relays, the public views our performance as a disaster,” said Logan. “Dropping a baton isn’t bad luck. It’s bad execution. We will conduct a comprehensive review of all our programs. Included in the assessment will be the way in which we select, train and coach our relays. Dropped batons were reflective of a pack of preparation, lack of professionalism, and lack of leadership.”

THE SOLUTION

I can save Logan and USA Track and Field a lot of time and money. I can save US sprinters a lot of guilt, anguish, shame — and a lot of useless practice reps and breast beating.

Of course my advice will be dismissed like as the delusions of an uncredentialed crank. I know it will be dismissed like the ravings of a peasant who says he has seen The Redeemer. Airing it in a public forum may lead to my license to practice journalism revoked for delusions of grandeur and spewing irrational nonsense.

Nonetheless, this works.

Really

Jim Simmons, my high school track coach at Seabreeze Senior High School in Daytona Beach, Florida, led his teams to state titles and great success for two decades. In particular, with one tragic exception that had nothing to do with technique, his sprint relay teams were rock solid reliable. As far as I know, they never dropped a baton in anything – from local dual meets to the highly competitive Florida high school track and field state meet. In my era, our 880 relay squad won the 1967 Class A state title in 1:30.6 and our sprint medley relay team placed third.

Simmons’ method was not voodoo and was not rocket science. But it had the brilliance of simplicity, and the power of consistency. It was stunningly efficient, didn’t take long to learn, and it was infinitely repeatable.

Better Doug Logan calls Jim, who is now about 75 years old and still winning amateur golf tournaments in Daytona, to explain. But here is the gist of it.

Calibration is no secret. But I’ll repeat the obvious for track and field newbies. It begins with a few run-throughs to determine precisely when the receiving runner must start. The object is to find the exact spot on the track that when reached by the oncoming runner, the receiving runner takes off. When done correctly, the teammates both reach a spot in the middle of the exchange zone at equal speed. When that spot is found, place a small piece of tape on that spot on the track. While 4×400 meter exchanges have a much wider variation in arrival speeds due to exhaustion variables, the 4×100 meter sprint should be extremely predictable.

The key to repeatable, reliable consistent success is the placement of the arms and hands. Forget about looking over your shoulder and waving your arms hoping the baton will magically appear. And say goodbye to weeping and gnashing of teeth and wondering if it’s Jamaican voodoo or the Almighty who had a grudge against you and your team.

Here’s what to do. After approximately four or five steps, the runner receiving the baton should be near top speed and ready to take the baton. At that point – and not before and not a step later – he or she should extend their receiving arm behind him at a 45 degree angle to the ground. Then keep running and leave your arm in place and at that same angle. The thumb should be positioned to one side and four fingers touching to the other side, making a stable, unmoving Very-shaped target – a running catcher’s mitt — which your oncoming runner could find blindfolded.

With the target hand in a predictable place, the oncoming runner should bring the baton from a position pointing straight down in an upward swing – like a pendulum – up into the awaiting slot between the thumb and four fingers. No banging it in, no holding on too tight and creating a disastrous fight for possession. Just bring it in with a light but firm touch and let the departing runner receive it, grasp it, take control, and run to glory.

THE SIMMONS METHOD DOES NOT REQUIRE ENDLESS PRACTICE.

What I see from the professionals is a crazy mess designed for failure. They look over their shoulders, contorting their bodies and trying to synchronize a connection on the fly. They wave arms like goslings learning to fly and miraculously connect by the grace of angels every once in a while. To reach over the shoulder and make the pass over the head and guessing where it will be is sheer, dysfunctional insanity. I know the Olympians are hurtling through space at 27 mph while our old high school runners were straining to reach 22 or 23, but all the more reason not to be guessing when to take off and where your hands should meet.

And while track commentators talk about practicing all year as a solution, it’s not necessary, Jim Simmons taught us once and after a dozen or so repetitions, it was engraved in our DNA. Practicing bad technique for hundreds of reps will simply groove in the bad habits and guarantee another century of chaos in the exchange zone.

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network