Road wheel basics

I’m not the sharpest tool in the shed, but I’ve noticed something in the triathlon industry over the past, oh, decade. There’s a certain category of products that is absolutely on fire in terms of popularity, sales, and geek-fueled debate:

Wheels.

Yes, those rubber-wrapped donuts on which you propel yourself. Once you’ve been around the sport for a while, it becomes easy to assume that everyone – including beginners – knows what you’re talking about. We assume that they know what ‘aero’ means. We think they know what a ‘racing’ wheel is and a ‘training’ wheel is. We think they know about different wheel sizes, rim materials, construction methods, and nuances of design. I’m guilty of this, and I imagine that many seasoned Slowtwitch readers are, too.

Today, we’d like to take one giant step back and attack the wheel topic from a very basic perspective. What are the truly need-to-know terms? What should I look at when considering a purchase? Should I own two pairs of wheels for one bike, or is one set enough? Let’s get on with this two-wheeled journey…

Wheel Anatomy

What’s in a wheel?

Those are the basics. Let’s zoom in on a spoke where it contacts the rim:

There is a little threaded nut that attaches the spoke to the rim, called a spoke nipple. He said nipple! Yes, let’s get that laugh out of the way.

This is the typical construction of a modern wheel. There are exceptions. Some fancy wheels have spoke nipples that thread in to the hub, with some sort of anchor built in to the rim. For example, some 3T wheels have this reverse-style construction:

There are some wheels with dual-threaded spokes (e.g. Easton), and some with molded-in carbon fiber spokes (e.g. Lightweight). I’d venture a guess, however, that about 90%+ of wheels have the traditional hub-spoke-nipple-rim configuration.

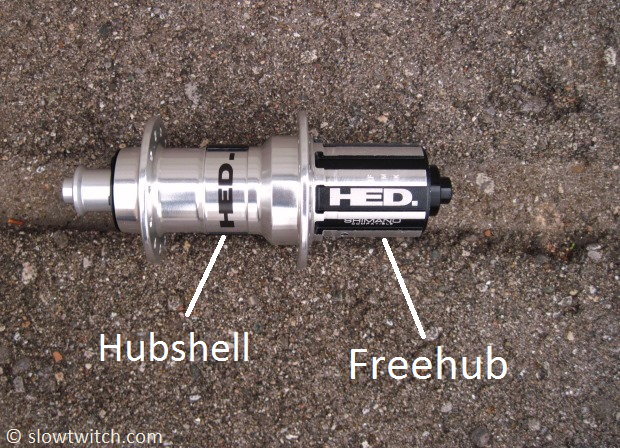

Let’s also take a quick look at the most complicated part of your wheels – the rear hub:

Your rear hub is special because it is what actually allows you to propel yourself forward on the bike. It takes all of that torque that your manly or womanly quads pump out and translate it into go-go juice.

All rear hubs must have some sort of clutch or ratcheting mechanism that allows movement in one direction (coasting) and lockout in the other (pedaling). This device is inside of the freehub and/or hub shell, and is typically referred to as a ‘drive mechanism’.

Also note that the freehub in the above photo has more than one name. It is also called a ‘freehub body’, ‘cassette body’, ‘driver body’, ‘driver’, and probably a few other names I’m forgetting. It is the part where your cassette (gears) go. There are different designs of freehubs, which are covered in the article linked at the bottom of this page – Cassette How-To – Part 2. You can also learn how to remove and install a cassette in the first segment of that article, Cassette How-To.

Wheel Sizes

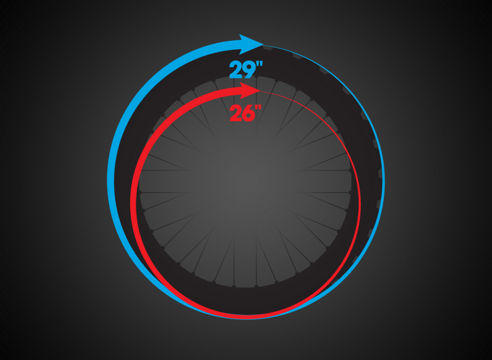

The next thing to understand about road-based cycling (including triathlon bikes) is that there are two different wheel diameters that are primarily used today: 700c and 650c. 700c is larger, and 650c is smaller. For the most part, larger bikes use 700c wheels and smaller bikes use 650’s. For the (very) long version of this discussion, check out Wheel Size Wars, linked at the bottom of this page.

How do you know which size your bike has? If you don’t know or your bike shop never told you, chances are it has 700c wheels. That is – by and large – the most common size. If you want to double check, a quick measurement of the rim will tell you. 650c wheels measure approximately 58cm in diameter (for the wheel, not the tire), and 700c wheels measure approximately 63cm in diameter. If you want to measure the tire, an average 650c tire will measure – you guessed it – 650mm (65cm), and an average 700c tire will measure 700mm (70cm).

There are other different wheel diameters, as mentioned in the Wheel Size Wars article. We don’t want to get too in-depth and will leave it at this for today.

Tubulars and Clinchers

If you’re new to the sport, you’ve probably heard some people say that their wheels that are, like, totally tubular, dude. Is this sport full of surfer bums? What’s going on?

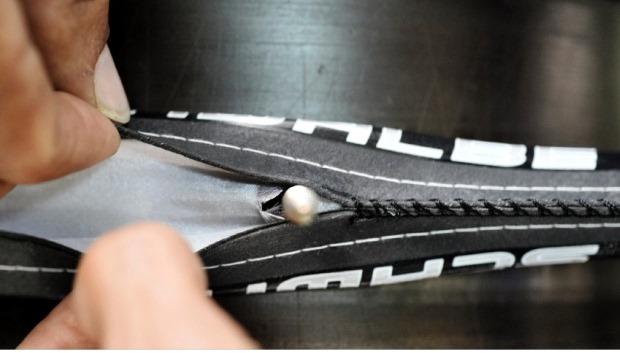

The word ‘tubular’ is referring to the type of wheel and tire, not how good or bad it is. The old-school name for a tubular is ‘sew up’. This name refers to the construction of the tire – most of them are literally sewn together:

Above image © Schwalbe

This type of tire gets glued on to the wheel. As such, the rim has a specific shape that must accommodate this:

Why would you want to ride tubulars? They have one distinct advantage: for a given rim material and overall design, they are lighter than clinchers. The rim does not need the bead hooks necessary for clincher rims, which we will discuss shortly. They also tend to have slightly better ride quality. The big downside is that you cannot simply put a new inner tube inside the tire in the event of a puncture – you must replace the whole tire. If you race with tubulars, that means you must carry a whole spare tire with you – not just an inner tube. You pre-apply some glue to it, fold it up, and find a place to attach it to your bike (e.g. under the saddle). My advice? If all of this is new information to you, do not ride tubulars. For nine out of ten people, clinchers are easier to deal with.

Here is a look at a clincher wheel, tire, and inner tube:

The tire and wheel mate with a mechanical interface. The rim literally has hooked edges, called bead hooks.

Both the rim and tire must be manufactured within a very specific window of diameter, or else the system won’t work. You cannot put a 650c tire on a 700c wheel, and vice versa. Even for a given size (e.g. 700c), not every tire and wheel fit together with the same ease.

Clinchers are similar to tubulars in that they have an inner tube that holds air (yes, super-geeks, there are some exceptions out there, such as Tufo’s unique construction). The difference with a clincher tire is that the tube is not sewn in to the tire – it is completely separate and can be replaced.

In addition, most modern test data shows that clincher tires have slightly lower rolling resistance than tubular tires, meaning that they require slightly less effort input from you to roll down the road (tech note: this highly depends on the materials and design of the tire/tube). Clincher wheels are always a little bit heavier than their tubular counterparts, but that in no way assumes that clincher wheels are heavy. It is still possible to build a very light set of wheels; it all comes down to how much money you are willing to part with.

We should also mention that there is a sub category of clincher tires – tubeless clincher tires. These feature special construction and no inner tube at all. For full details, check out our All About Tubeless article linked at the bottom of this page.

Wheel Materials

Let’s talk about what your wheels are made of. Do you keep hearing about carbon wheels and how great they are? What other materials might a wheel be made from?

The first thing to understand is that it is very rare to have an entire wheel made out of a single material. If someone has ‘aluminum wheels’, it is not as though the rim, hub, spokes, axle, bearings, and every little thing are all made of aluminum. What they’re typically referring to is the material of the rim.

Here are the most common materials that may be used for the various parts of a wheel:

Rim: Aluminum, carbon, magnesium

Hub and hub parts: Aluminum, carbon, steel, titanium

Spokes: Stainless steel, aluminum, carbon, synthetic fiber

Spoke nipples: Brass, aluminum

The tricky part is that the buying process for does not usually get this detailed. Often you see ads for ‘carbon’ wheels, but that could mean a lot of different things. Some ‘carbon’ rims, such as this Easton EC70SL, have a hybrid construction – an aluminum outer rim mated to a carbon inner section:

Some rims, such as these Roval Rapide CLX60s, are ‘full carbon’ clinchers – meaning that the entire rim is made from carbon, and it accepts clincher-style tires and tubes:

When you really get detailed, you learn that even ‘full carbon’ isn’t really accurate. Many carbon rims have fiberglass braking surfaces, and different materials inside of the rim such as foam or aluminum. Most of these things aren’t really going to affect you too much, but it is worth asking (a lot of) questions before plunking down your cash. Just because a wheel has ‘carbon’ in the name does not necessarily make it any better, faster, lighter, or better-functioning than any other wheel. Just like other consumer products, it’s all in the quality of build, choice of materials, and service after the sale.

Racing wheels vs. Training wheels

Do you want a pair of super-fast race wheels? Surely they’re faster than measly ‘training’ wheels. They must automatically gift a free 2mph to your next Olympic distance bike split, right?

Well, maybe.

Here’s the big secret. Just like tires, there is actually no such thing as a ‘race’ or ‘training’ product. They don’t exist. There are no actual definitions, rules, or governing bodies to regulate those words. Often times people assume that certain attributes are automatic qualifiers in to either category:

“All aluminum wheels are just training wheels.”

“Oh, you have carbon race wheels? Cool!” (implying that ‘carbon’ and ‘race’ are intrinsically linked)

“I’m going to put my race wheels on. I have a deep 60mm front wheel and rear disc, so I’m going to smoke the entire field at tomorrow’s race.”

True, many carbon wheels do qualify as ‘race’ wheels. Some modern aluminum wheels even qualify as ‘training’ wheels. What I’d like to do is lay out a few definitions and things that actually force a wheel into either category.

Training wheels:

-Their first priority is strength and durability. This should include not only the rim, but also the spokes and hub design.

-Low cost is also a priority. Replacements must be affordable and readily available.

-Given the previous two points, this means that a training wheel will necessarily be heavier than a racing wheel for a given rim depth and overall design. In auto racing, there is a common phrase that is used for buying parts: “Light, strong, inexpensive – pick two”. It’s true. The word ‘strong’ can also be exchanged with ‘reliable’, ‘worry-free’, ‘long-lasting’, etc. You get the point.

-Things like aerodynamics and aesthetics take a back seat.

Racing wheels:

-Performance is #1. This means light weight, aerodynamics, low rolling resistance, and overall efficiency.

-Price tends to go up compared to training wheels.

-Looking at our light-strong-cheap scenario from above, we might think that a wheel that is both light and expensive is automatically strong, too. I’ll give a qualified ‘maybe’. While a hike in price normally means that durability increases, it gets complicated with bike parts. It is not uncommon to see a super quality rim laced to sub-par spokes and nipples (or vice versa). Companies know that every penny counts. As another example, many race hubs are super light (and expensive), but have a big compromise in longevity. The actual materials of the hubshell might have an outstanding strength-to-weight ratio. However, that hub might have virtually no sealing from moisture and dirt (for low rolling resistance) – meaning that you must replace the bearings every 6 months. ‘Durability’ of the hubshell says absolutely nothing about the design of the bearing seals; they are two separate parts. Got it?

The big take-home with training and racing wheels is that you should look for specific features that you want – features beyond ‘I want CARBON!’ What you really want are light weight and aerodynamic, and some light/aero wheels are made from carbon fiber. There are, however, carbon wheels that area heavy and not-aero, or aluminum wheels that are light and fast. You can also find aluminum wheels that look like training wheels, but have poorly-sealed hubs, corrosion-prone spokes, and a soft aluminum freehub.

Here are a few features that you can ask for at the bike shop when making that next purchase.

Good training wheels tend to have…

-More spokes

-Thicker spokes

-Brass spoke nipples

-Spoke nipples that are visible through the rim (e.g. ‘external’ – for easy adjustment)

-Large bearings inside the hub

-Substantial bearing seals and grease

-An aluminum rim that is not the lightest on the market

-A steel freehub (light weight aluminum freehubs tend to be much more fragile)

Good racing wheels tend to have…

-Fewer spokes

-Aero spokes

-High quality aluminum spoke nipples (e.g. DT Pro Lock)

-Smaller and lighter bearings

-Lighter bearing seals

-Deep-section and/or wide aerodynamic rims

-Aluminum or titanium freehub bodies

Do you NEED two sets of wheels (e.g. a pair of training wheels and race wheels)? Absolutely not. They are nice to have, though. Beyond the obvious speed benefit of the race wheels, having two sets leaves you with a backup in case of a mechanical problem (e.g. broken spoke, bearing replacement, etc).

Rim Width

The topic of rim width is a hot one these days, and I’d like to touch on it from a practical perspective. Many wide rims are legitimately more aerodynamic than narrow rims (especially with modern tire sizes), so the average rim width is slowly growing. That’s all fine and dandy with this editor.

The key implication that this has is it complicates your brakes. If you train on a narrow aluminum rim and race on a wide carbon rim, you must completely change your brake setup when you change wheels. The two rim materials require different brake pads, and the width of the brake must change to accommodate the two rim widths.

If your bike has standard caliper brakes (pictured below), the adjustment is relatively easy. If you don’t know how to do it, your mechanic can probably teach you in about five or ten minutes in exchange for a frosty 6-pack of fermented beverages.

The issue with modern triathlon bikes is that most of them have brakes that are proprietary in design and/or hidden away under fairings, behind chainrings, and under bottom brackets. If you are an experienced ‘wrench’, you can probably handle the adjustment, but many people cannot. You’re often required to move spacers around, adjust the brake cable, and remove extra parts just to access the brake.

That being the case, I highly recommend buying training and racing wheels that are the same width, and ideally the same braking surface material. If you race on a carbon braking surface, you should train on one too. Same goes for aluminum. If you the two rims have an identical width, you don’t have to do any brake adjustments and life is peachy. You may still have to adjust the rear derailleur slightly, unless the two wheels have the same model of rear hub.

—

What do you think? If you’re a beginner, is all of the wheel talk overwhelming? Are you confident in your next purchase? We’d love to hear your comments.