SportieDoc breaks through

Her twitter handle is jaunty – @Sportiedoc. Her sporting heritage through her father goes back to the Tour de France in the 1960s. As a kid she was a swimmer, runner, mountain biker and an accomplished equestrian and target shooter. As a teenager, she suffered and survived a serious eating disorder. As a multifaceted doctor, she studied neuroscience, psychiatry and mental health, and has done extensive research on eating disorders, sports nutrition and heart damage in endurance sports. Upon gaining her degree and starting her residency, she decided to trade the security of working as a full time physician for the risky, uncertain life of a professional triathlete.

Rising above the usual disappointments, Lewis has had cause to celebrate her sports career. She has been guided by top coaches such as Michelle Dillon, Bret Sutton and Cliff English and earned several podiums in Olympic distance and middle distance events. And two weeks ago, in her first Ironman test, she conquered the rugged Ironman UK course and won by an impressive 19 minutes.

Through it all, Dr. Lewis will make her biggest mark in life with by combining her sports experience with her medical expertise and passing on that knowledge with a remarkable candor and eloquence.

BACKGROUND

Slowtwitch: Tell us about your dad in his Tour de France days.

Tamsin Lewis My dad Colin Lewis was a professional road race cyclist with 38 professional career wins. He represented the UK in the Tokyo Olympics and rode in the Tour De France in 1967 and 1969. He was from very poor Welsh mining family and was the last Welshman to ride in the Tour until Geraint Thomas in 2007. He is a grafter, and hard man, who still rides his bike 5 times a week at the age of 74. He owned a bike business, Colin Lewis Cycles, for 30 years in Southeast England and now painting is his passion.

ST: You mention he was a domestíque for Tour de France teammate Tom Simpson who died in 1967 on Mt. Ventoux – and that he handed Tom his last drink before that fateful climb. Do you have any thoughts on Simpson’s use of amphetamines and alcohol that led to his death?

Tamsin: Dad often speaks about those times. He shared a room with Tom and would see his container of pills by his bedside as Tom would count them out. It was accepted and not particularly covert in those days, but according to Dad relatively rare as the costs of the drugs themselves meant that only the GC contenders had access to them.

ST: How crude were those drugs?

Tamsin: The drugs they used were like taking a shot of heroin for a headache – dirty, strong and potent with a host of horrendous side effects. The effect on the heart of a mix of speed (amphetamines), alcohol, steroids and dehydrated blood is profound. — like pumping syrup. Would Tommy Simpson have died on the Ventoux if he had been clean? I am pretty sure not. The use of the substances mentioned allowed riders to push past any homeostatic, central governor (shut down) mechanisms to a point where he was beyond resuscitation.

ST: How does that knowledge make you feel?

Tamsin: It saddens me as a medic. Was Tommy Simpson informed of the potentially damaging side effects and risk of death by his medical team? From what I hear from Dad, there was a lot of naïveté about the risks. I think the science behind cycling in those days was pretty basic.

Drugs aside, Dad would talk about 5 hour training rides after a salted kipper breakfast with only half a bottle of water to ‘acclimatise’ to the dehydration. He still goes out for 3 hours without a drinks bottle, and he wonders why he has gout!

LOVE OF SPORT FROM THE START

ST: Sporty lass growing up you were indeed ! Tell us about how your family encouraged your love of swimming, cycling and riding as a kid?

Tamsin: My parents separated when I was 8. My mother Julie is an academic but was also always very active. She taught high school English, History and Drama. Mum threw us into every sport going. My grandfather was a deputy head teacher and maths professor. Growing up he was a national swim champ and so he would take me to swim galas. I competed at a regional level in swimming, but gave up when I was 12.

ST: I hear you competed in tetrathlon as a kid. What is that?

Tamsin: Pony Club Tetrathlon was all the rage. It is a precursor to Modern Pentathlon – a 2-day event with target pistol shooting, 3km running and swimming as far as you could in 3 minutes. I would do over 9 laps of a 25 meter pool — probably as fast as I swim now — at the age of 11! It also included a cross country jumping on a horse. I loved it and won most of my competitions.

THE RAVENOUS SHADOW OF EATING DISORDERS

ST: You have written that you fought eating disorders as a teen. Why is this such a widespread problem in society?

Tamsin: This is a difficult question to answer and deserves a full article in its own right. There are genetic influences in the development of eating disorders – particularly anorexia – but the environment encourages expression of that gene. It is often a downward spiral for those at risk. A teenage diet to lose puppy fat in some is just that – a week of ‘SlimFast’ and then back to eating cheesy chips with friends. For me and many others with the anorexic trait, that diet set in chain a series of behaviour patterns which became addictive and were reinforced by the endorphinic high of semi-starvation.

ST: What were the emotions propelling it?

Tamsin: Some dismiss it as attention seeking – and initially when a chubby child loses weight, the praise and attention can be thrilling. But as the spiral continues, the disease is propelled by fear. I was literally terrified of eating – the changes in brain chemistry in anorexia and bulimia are far better understood now – but it is highly pathological and still has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric illness.

ST: What are the societal triggers?

Tamsin: People blame the media for the increased incidence of eating disorders, with the female role model shape changing over the years. Yes it doesn’t help, but I don’t think that is why anorexia develops. Perhaps it is encourages the development of binge eating disorder, and then bulimia as girls become desperate to achieve a slim body through uneducated means of weight control — the starve/binge cycle.

ST: Why it is often seen among high level athletes?

Tamsin: The sport attracts perfectionists and those with addictive traits. How these are expressed depends on the individual, but one’s ‘drug of choice’ can vary.

ST: What is the cost of this disorder to athletes?

Tamsin: It is impossible to perform at the top level in any sport, for any amount of time – especially endurance sport – with a strong eating disorder. We often learn this the hard way, but I think Chrissie [Wellington, who wrote about this in her autobiography] realised through her early time with coach Brett Sutton that she needed to fuel herself in order to be the best she could be – so she did. Sport for many improves their relationship with food as we see it as fuel to strengthen, rather than calories to fatten. I learnt from being immersed with the strong women training with Team TBB that strong wins over skinny every day. My own body has changed to reflect this.

ST: While coaches and athletes know better, why is this disorder still a temptation?

Tamsin: For those in the sport already – obsession with food and weight is immense. Race weight becomes the be all and end all. Feed your body adequate nutrients, micro and macro, and it will come to balance at its naturally desirable weight. Fighting this often ends up injury or illness.

ST: What were your emotions as this disorder began to take hold?

Tamsin: I have always been a little cheeky. As a child I would be inquisitive and spent a fair amount of time in the naughty chair. But teachers didn’t mind too much as I always did well in the work I was set. I had a difficult childhood and acted out a little perhaps to gain the attention of my warring parents. Then as I progressed into my teenage years I went inwards as the anorexia consumed me and my energy. In recovery I re-identified with some of my extrovert personality and my confidence returned.

ST: When you look back on your battle with this disorder, what do you see?

Tamsin: I look back on my time spent battling eating disorders with sadness. I wasted a great deal of time, energy and money and broke down my body to its base layers. I was lucky to have strong genetics and good nutrition through my child hood — otherwise my bones and heart may not be as resilient as they are. I think fear perpetuates eating disorders. The behaviour — whether it be starvation, bingeing or vomiting — is like a comfort blanket. It takes you back to what you know and diverts attention from external pain. But eventually the problems caused by the eating disorder supersede that of the original emotional pain and it becomes all-consuming.

ST: What was your key to breaking away from this affliction?

Tamsin: When I started to break behavioural patterns – feel my fears and do the things I feared anyway – things started to change. The external pain became more manageable. Triathlon is part of that – you put yourself into fearful situations and get through. This teaches the mind that you can do far more than you think you can.

ST: What can athletes do to fight this?

Tamsin: I run a company CuroSeven.com which analyzes blood tests from athletes all around the world and as part of this we look at the influence of diet and supplements on athletic physiology. Carb restriction has become the new bandwagon. Done without proper advice, it leads to a host of problems including hormonal disruption – in particular – thyroid. People wonder why they are training 20 hours a week eating a Paleo Diet and not losing weight.

BECOMING A DOCTOR

ST: What led you to medicine? What qualities and backgrounds of your family contributed to this ambition?

Tamsin: As a child I was fascinated in everything. Becoming a doctor was a natural progression for me as I wanted to save the world. My Grandfather nurtured this ambition in me. As a mathematics professor, he encouraged my intellectual development as much as he did my sporting.

ST: What led you to focus on neuroscience and the anatomy of the brain?

Tamsin: The brain controls everything – and I was keen to get an in-depth understanding of neuroscience. However, the more I learnt, the more I realised how little we know. The advent of more advanced imaging techniques is likely to change this. I had an inspirational Neuroscience lecturer/professor and she guided me on the path. After qualifying as medical doctor, I spent 2 years as an intern and then specialised in psychiatry and mental health.

ST: Does that specialty inform your approach to sport?

Tamsin: It helps me to understand myself and others’ behaviour. However, understanding is not mastery. I self-analyse, adjust and recognise when it’s ‘mind over matter.’ I use psychological techniques in preparation and during the race. Sometimes the best thing can be not to think – just do. Quiet the mind and let the body do what it has practiced.

BECOMING A TRIATHLETE

ST: What led you to triathlon?

Tamsin: My boyfriend at medical school did triathlons and I used to watch in awe, quite unable to understand how one keeps going for that long. I longed to do one, but never thought I could. Plus I was too busy working junior doctor hours and then drinking too much to switch off. I entered the London Triathlon twice before actually making it to the start line.

ST: So how did you finally pull the pin and do one?

Tamsin: In 2007, I went on a couple of dates with Charles Pennington – a superb athlete who later won silver in 30-34 in the 2012 Vegas [Ironman 70.3 World Championship] amongst other wins. He convinced me to do the Blenheim sprint triathlon. I did it on 5 hours of training a week and won my age-group. I was hooked! Then at the London Triathlon, my first Olympic distance, I was picked to be part of the Herbalife Triathlon Academy run by Bill Black. The rest is history.

ST: Congratulations on surviving the freezing cold waters at the 2008 ITU Worlds in Vancouver. Why did you not quit the sport right then and there? Brrr!

Tamsin: I did say ‘never again’ at the finish. The swim was horrendous. We were the last group to swim before they cancelled it. I survived, and had a good bike, but slipped on mud in T2, sprained my ankle and hobbled to the end for 11th in AG.

ST: How did former top ITU athlete and current coach Michelle Dillon guide you to a gold medal at the 2009 ITU Age Group World Championships in Australia?

Tamsin: Meeting Michelle changed my world. Her enthusiasm and energy were infectious and she had 100% belief in me. The training intensity was hard, but it worked for me at the time. And having her there with Jodie Stimpson cheering for me on the day was superb. I led from start to finish – a day I will treasure forever.

ST: What have your coaches thought of your psychology background?

Tamsin: Brett Sutton used to say that I would be a better athlete if we could chop my head off. I have matured as an athlete since that point, both in my self-belief and ‘race-head,’ but still any athlete can get immersed in self-doubt after a run of back luck or injury.

ST: How did your work in psychiatry – addictions, schizophrenia and dementia – inform your work with coaches and your approach to triathlon?

Tamsin: It plays a part in different aspects. Psychological aspect – mental preparation for racing and dealing with setbacks. Psychiatric aspect – awareness of a propensity of myself and many in the sport to train for training sake. Cross-Addiction – the equivalent of burying the head in the sand by not dealing with other emotions/fears/relationships. Training to the point of exhaustion so there is little energy left for anxiety or to deal constructively with either deep-rooted/everyday problems. Overall, recognising that training specificity is more important that just head-banging day in day out.

ST: When does triathlon step over the line into the pathological?

Tamsin: Many of us are on the spectrum of mental illness. The sport attracts extremists whether it be those of the spectrum of OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder), Autistic Spectrum Disorder, Eating Disorders or Addiction. Perhaps being addicted to triathlon is better than being addicted to drugs and alcohol — but when the addiction starts impacting areas of your life outside the sport, the situation becomes untenable long term. Often these are the people who become repeatedly injured or fatigued from over-training. Difficult to address when the culture of the sport is one of TTFU [“Tighten The Fuck Up”] and Death Before DNF [Did Not Finish].

ST: Were you at all torn by your decision to interrupt your progress as a young doctor to become a professional triathlete?

Tamsin: I probably would have never done it had my workplace not been so supportive. They held my job open for up to 3 years and I was also given some financial sponsorship by the company I worked for. I am forever grateful to my boyfriend of the time (a long term triathlete) for giving me the push and support to take the step. Medicine is a very secure job – I left a lot of security behind, financially and psychologically, when I stepped down. But the adventure has been worth it every step of the way.

DRAWING THE LINE

ST: Tell us about your experience with different coaches?

Tamsin: Brett Sutton was my first coach as a pro. My boyfriend put me in touch with him and he wrote back on finding out I was a psychiatrist: “Tell her – she can’t out psych a psycho” – referring to his own personality/coaching style. It was a very testing time for me – physically and mentally. Brett pushed all my buttons. Brett made me furious, tearful, joyful, anxious, embarrassed, adolescent, jealous and jubilant.

ST: How did you respond?

Tamsin: As a manic depressive, I could recognise his mood swings and I was occasionally at the brunt of them. Going through chemotherapy for testicular cancer only exacerbated his mood swings.

ST: Was there a confrontation that stood out?

Tamsin: I brought a water bottle to the pool as when we wore a wetsuit Brett would allow them. I had taken the wetsuit off but had a sip from the bottle. He lost it – throwing the bottle at me and emptying the contents poolside, He was livid at me for ‘ruining his environment.’ I was shaking and in tears. I hadn’t felt this small since I was put on the naughty chair in kindergarten. After, I spent an hour on the phone to my boyfriend crying, saying I had to leave the squad and come home.

ST: Did you?

Tamsin: I didn’t come home then. Brett found a way of apologising indirectly, but said it had been a test. It didn’t feel that way – it felt like rage. But he had a point – if I wanted to stay on the squad I had to learn to toe the line. Ultimately it is why we didn’t work out as coach and athlete. He would have me do things just for the sake of it (perhaps to mentally prove that I could). But I felt like it was breaking me down, not building me up.

ST: How do you evaluate that time?

Tamsin: I will always cherish the time I spent with Brett and the Team TBB squad. I learnt more about myself in that year than I did in the previous 10. It is only when we are stripped down to our core that we realize what we are truly made of. I respect Brett and the way he reads an athlete is truly exceptional. There is no hiding. He is the most obsessive coach I have ever come across – he eats, sleeps and breathes his athletes. His coaching style is one of dictatorship. I would not submit.

ST: What is your relationship with your current coach?

Tamsin: I have a collaborative relationship with Tom Bennett of T2Coaching. He respects my scientific knowledge and me his. But he reminds me that I can be my biggest critic and will tell me how it is and give me a kick up the proverbial if necessary. My professional knowledge of physiology and the central fatigue governor – have led us to approach fueling strategies a little differently.

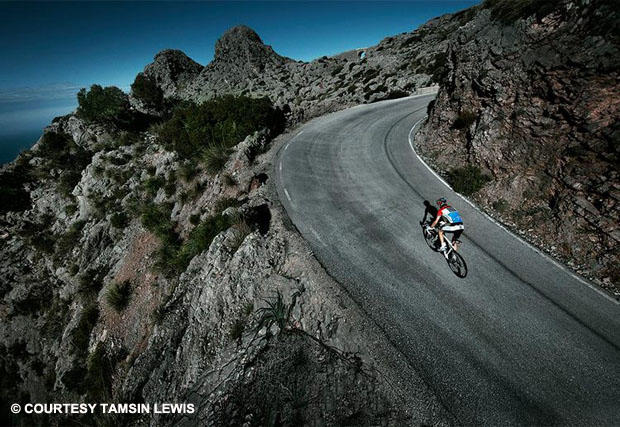

ST: When you trained in the Alps with Sutton and raced the Alpe d’Huez triathlon, did you think you were following your father’s footsteps?

Tamsin: I refer to the Alps as my spiritual home. I am most content when climbing mountains. It’s no coincidence that I am a good climber. I often thought about ditching tri and taking up cycling – but the crashes in women’s racing always put me off. However, never say never. I completed La Marmotte this year – a cycle sportive 110 miles in length, 5000 meters of climbing — and really enjoyed it.

ON THE RISE

ST: After working with Michelle Dillon, Brett Sutton and Cliff English you had several breakthroughs and seemed to be on the verge of greater success when you left Cliff English. Why did you leave him after 2012?

Tamsin I enjoyed Cliff’s coaching and his knowledge base is immense – but preferred a more hands on approach which was difficult with Cliff being in Arizona and me in the UK. I also had a number of personal problems outside of the sport in 2011 and 2012 which affected my racing.

ST: How did you get through the inevitable ups and downs?

Tamsin: The support of my then boyfriend – Declan Doyle – who had unfaltering belief in my physiological ability. And the fact that persistence and tenacity are two of my positive characteristics.

ST: You had quite successful season in 2013 – 2nds at Ironman 70.3 France, Gerardmer XL, Alpe d’Huez, Ironman 70.3 Italy. You were on the verge.

Tamsin: 2013 was my best season. I started working with coach Tom Bennett who has spent a big chunk of time working with Darren Smith (coach to multiple Olympians). Tom changed my swim and run technique and made me more efficient.

ST: How did it feel to be chasing a big professional win?

Tamsin: I gained confidence from my early races in 2013 but it was frustrating to be close on so many occasions. I would be lying if I told you that the thought of just not being good enough hadn’t crossed my mind.

ST: How did you feel about getting pipped at the line at Ironman 70.3 Italy?

Tamsin:I had a bike crash just days before the race riding on wet roads on the course. My knee and my hip were swollen. I knew running was going to be tough but it was honestly the most painful 90 minutes of running ever. I had a 6 minute lead off the bike, but knew Erika Csomor was a good runner. I didn’t realize she was so close to me (crowds of runners on the course and no spotters) and with 200 meters to go she caught me. Usually sprint finishes are my thing, but I had nothing left.

ST: What was it about your 2014 season that set you up for your big day at Bolton?

Tamsin: I have been training well all year and yet had a number of problems leading into races. A peroneal injury before Challenge Fuerteventura nearly meant I didn’t start. Ironman 70.3 France was a last minute decision to race – one week after I crashed in 70.3 Mallorca (avoiding a goat on the descent) – so my physical condition was subpar. Anyone who follows me on @Strava [An app which allows athletes to track rides with a GPS device and share it on the Internet] could see my run and bike were in good shape. I just hadn’t had the chance to reflect this in a race.

THE BREAKTHROUGH

ST: Why Bolton?

Tamsin: Ironman Nice (June 28) was my dream race with its mountainous bike course. However, my run injury flared up and we couldn’t get the miles in. It was touch and go leading in to Bolton [July 19]. I knew the bike course was tough – the more technical and hilly the better for me. I had heard super reports about the crowds at Ironman UK and I also had a number of friends racing. All those little things gave me a positive mindset on the day.

ST: How ready were you?

Tamsin: I was physically fit. I had been looking after my nutrition and supplementing as my blood tests indicated. I regularly test my blood through our company (www.CuroSeven.com) to keep on top of micronutrient deficiencies, and hormone balance. The run injury was still a concern, but team-mate Parys Edwards (2nd at Ironman 70.3 Denmark in his pro debut) served as a physio on hand to do soft tissue release and taping so I could perform. I hadn’t done any long brick runs off the bike (or practiced my race nutrition) so I had no idea how my legs would hold up on the marathon.

ST: Tell us about your race.

Tamsin: The swim was super easy – I actually felt like I body-surfed the last 1.9k in the swim draft.

ST: After the swim, how did you feel starting the bike 3:50 down to Katja Konschak?

Tamsin: I was never worried about being over 3 minutes down. I am confident in my bike strength and knew Katya wasn’t a big hitter on the bike.

ST: Were you being careful not redline chasing Katja?

Tamsin: I was über conservative on the bike. But it was one of those wonderful days when it just flows. I held myself back a bit, but rode over my coach-prescribed watts all day as perceived effort was low.

ST: How did you feel when you took the lead?

Tamsin: I caught Katya about 15 miles in at the top of a climb and she didn’t mount a defense. The TV motorbike told me at one point that she was catching up. Not sure if this was correct information, so I pushed a bit.

ST: How careful were you?

Tamsin: Throughout the bike I had to tell myself – focus! It was so technical, a moment’s lapse in concentration could result in overcooking a corner. I nearly came a cropper on one wet, gravelly road, but managed to correct. I also made sure I fueled as much as possible, but I got this a little wrong as I had to vomit at 80 miles. So I drank water and slowed a bit on the carb consumption.

ST: How did you feel when you got off the bike with a 14 minutes lead?

Tamsin: I came into T2 smiling. My boyfriend and friends were there screaming support at me. I had no idea what the lead was until I was into the third kilometer when Joanna Carritt came into T2. Annie Emmerson was on the side of the road cheering and said, ‘This is your race Tamsin, you CANNOT lose this!’ From that moment I was determined that I would not.

ST: How did you feel about your 3:18:04 for your first Ironman marathon?

Tamsin: I thought it was too slow. However, it is a tough run course, with lots of hills and twists and turns. I was on pace for 3.08 until the last lap, when my legs and hip flexors started to feel it. I started to walk up one of the hills and quickly realized that if I walked it was highly likely that I might not be able to co-ordinate my legs to run again! This is where having not run more than 3 times in a month the last six months came into play. But cardiovascularly, I felt completely comfortable.

ST: You won by miles when you were not at your best. What does this bode for the future?

Tamsin: I will build back stronger from this and run faster in the next race.

ST: What are your feelings about this victory?

Tamsin: I was over the moon as the finish line pictures show. It’s been a long time coming. The support of the crowd made the final miles highly emotional. I had tears of joy and was stuttering in my breath!

LOOKING AHEAD

ST: Are you interested in a Kona start?

Tamsin: I have been to Kona three times and worked as a medic, experiencing the highs and lows of the race from the sidelines. But the desire to do the race has never been as strong as many other athletes.

ST: What have your coaches told you?

Tamsin: Brett always told me it would never be my race and he is right – non-wetsuit swim, flattish bike suiting stronger, bigger riders. And the run? Well I might be OK at that bit as I am good in the heat. It is pretty difficult as a newbie to Kona to qualify. I would have to podium at another Ironman within a month and then to do Kona a month later. Three Ironmans in 3 months as a newbie to the distance is a big ask.

ST: You have studied and written about the risks to the heart associated with Ironman training and racing. Do you have any ambivalence about racing the distance yourself?

Tamsin: In my opinion chronic endurance training and racing can be damaging to the heart. Especially those who regularly push their limits and try and override their central [nervous system] governor. However, it really depends on how much you respect your body. If you take an off-season, have other interests outside the sport and keep an eye on your hormonal levels (cortisol, testosterone, thyroid) and micronutrient intake and you are not too restrictive with diet, you could be fine. More important than anything, have fun – real joy – from the sport. Then the likelihood of developing a heart condition is reduced.

ST: Have you studied the physical consequences to the heart?

Tamsin: The heart is like any muscle. Repeated work sometimes results in tears of the muscle. Most of these repair with no residual damage. But in other cases, scar tissue replaces the muscle tissue and can set up the heart for an abnormal rhythm.

ST: What should triathletes do to guard against a catastrophic heart condition?

Tamsin: It is important as an athlete, amateur and elite, to have a yearly check of your heart. ECG (Electrical trace) at the very least and have a trained physician listen to your heart. If you experience palpitations, have a family history of heart disease or experience any unusual shortness of breath during exercise, seek out a sports cardiologist’s opinion. A 7-day ECG or even a 24-hour ECG tape can identify a number of heart rhythm abnormalities that a single ECG might miss.