The Superform

How appropriate. I'm sitting here at my keyboard listening to Hell Freezes Over. Glen Frey says, just before the Eagles break into Take it Easy, "And this is how it all started."

As I write this there is a thread on triathlon's popular usenet newsgroup rec.sport.triathlon. Yet again (as happens about every 18-months) someone asks about the beginnings of the bike technology that has make our sport unique. I thought I'd answer the question here, and with some photo representation.

The aero bar — as we know it — was invented by Boone Lennon. It first became apparent in our sport in 1987. Yes, it is true that a lay-down apparatus did appear in long-distance racing earlier in the decade on RAAM rider Jim Elliott's bike. Both Richard Bryne — founder of Speedplay — and RAAM winner Pete Pensyres were involved in that project. The main difference between that bike and the handlebars Lennon introduced was the concept of narrowness. Elliott's forearms were at brake-lever width, as opposed to the mock-downhill-skier position espoused by Lennon. Indeed, the bars were "Scott DH bars:" DH for downhill. The idea behind Elliott's position was comfort; the idea behind Lennon's bars was aerodynamics: precisely the position achieved by a downhill skier while tucked.

I have read the patents, but I've never had the patent file pulled. Only with the entire patent file would one discover whether Lennon had disclosed Elliott's bike as (what is termed in patent law) "prior art." That might have a bearing on Lennon's patent validity. I take no position on whether or not the patent is or was valid. Regardless, Lennon has maintained over the years that his bars were significantly different than anything prior, as is explained above. He certainly started the craze. There is no doubt in my mind that if Lennon had not introduced the bars we'd still be riding old-style road technology. Roy Wallack wrote an excellent piece on the history of aero bar development in Triathlete Magazine about three years ago.

That is half the story. The other half is the development of the bike that goes with the bars.

Several things were going on during 1987 and ‘88, all of which were to converge and conspire to produce the first tri-specific bike. I started a company in 1987 called Quintana Roo and it was, at that time, simply a maker of triathlon-specific wetsuits. I occasionally wrote articles for Bob Babbitt's "Running and Triathlon News" magazine, which eventually became Competitor Magazine. I had noticed that a few pro athletes — namely Scott Tinley and Gary Peterson — would occasionally wear surfing wetsuits, and I was surprised that they didn't swim more slowly than if they had worn no wetsuit at all. I therefore reasoned that if you actually made an effort to produce a wetsuit that had swim-specific characteristics, you could actually make it easier for people to swim in cold water without the wetsuit being a detriment. Babbitt and I thought an investigative article on this subject would be interesting.

I searched around for a willing contractor to aid me in this effort, and I found just such a company in Victory Wetsuits, a maker of surf wetsuits based in Huntington Beach, California. The owners allowed me to putter around in their factory; work on patterns; talk to their suppliers; learn from their workers; and eventually I came up with a design that I thought would work nicely. The suit was faster than I ever expected, as it turned out.

I wrote the article, but more than that — when it was all over — I felt like the guy who sprinted for a bike prime and found he was 200-yards ahead of the field. Now what do I do? I seemed to have an idea for a product triathletes were going to want. That was the genesis of Quintana Roo.

1987 was the year of triathlon innovation. Three new products made their entre into the sport, all at precisely the same time. In a strange quirk, the same two athletes were early users of all this technology. Brad Kearns and Andrew MacNaughton, fast friends in every way that the term construes, got out of the water in QR wetsuits, pedaled out of the transition area on bikes with Hed Wheels, laying their bodies down on Scott DH bars. Yes, disc wheels had previously existed, but Hed was the first company to make this technology affordable to athletes, pro and age-group alike.

Pro athletes needed one race in order to figure out what the wetsuit was all about. Andrew MacNaughton had never gotten beat out of the water so badly by his friend Kearns , and all it took was one L.A. Triathlon Series race at Bonelli Park for MacNaughton to realize that his friend had pulled a fast one, technologically speaking. At the very next race MacNaughton had a QR wetsuit. Paul Huddle got his QR wetsuit and while he was known primarily as a top runner, Huddle began a string of races in which he came first out of the water. By May every top Southern California pro was in a QR wetsuit. The first-ever user of a QR wetsuit was – by the way – longtime pro Mark Montgomery.

But it took awhile for age-group riders to catch on. I still have a photo from the Bakersfield Californian showing the pro start of the race — at that time a favorite stop on the pro circuit. Every pro in the field was in a wetsuit, yet just behind, in the age-group wave, the photo showed only one of the entire group of swimmers had a wetsuit.

I thought it was incumbent upon me to sponsor athletes, and I did so with reckless abandon. I had absolutely no idea how to run a company. Budget? What budget? Among those whom I sponsored — wanting to be an equal opportunity benefactor — were women. As I investigated the problem of women's race bikes, it became obvious to me that women were difficult to fit — especially when their bikes needed to be affixed with aero bars. Specifically, the bikes were too long from the bottom bracket to the front axle. The only way to fix this was by making the front wheel smaller.

I was not the only one to notice this, and just at that time the Terry bicycle was gaining fame. Georgina Terry's approach was to make the front wheel quite small — 24" — and leave the rear wheel large — 700c. I thought the problem would be more elegantly solved by simply shrinking the bike down proportionally, using 26" wheels in place of 700c wheels. We started making such bikes, and this was the beginning of Quintana Roo's bike business.

One of the first and by far the most successful of all the riders of these bikes was Liz Downing (pictured left), who went several years without losing a duathlon. She began her career riding QR's small-wheeled bikes and retired without ever riding another brand.

I was racing a lot in those days, and I found it very hard to get comfortable and powerful while using DH bars. We were all experimenting, and it became obvious to a lot of us that our saddles needed to be further forward than they were normally positioned on our road bikes. I approached the notion of bicycles the same way I did with wetsuits, namely, how would one modify an existing bicycle in order to make it perfect for triathlon? Or to put it another way, what if you build a bike from the bars back? How would it look?

I decided that I was not smart enough to figure it out on my own, that the best way to do it was to go into the transition are and start measuring the bikes of all the pros. I wanted to see what you could find in common among the way they set up their bikes. I plotted all this data, and came to certain conclusions. These conclusions were the basis of how I designed QR’s first tri-bikes.

During this process I had a regular association with a gentleman by the name of Ralph Ray, inventor of a variety of products, and a well-known figure to those who've been around the sport for at least a decade. I remember inviting him and his wife over for dinner one night near the end of 1988, for the reason of explaining to him my new idea. He agreed to come to dinner and — unknown to me at the time — his idea was the same: He had a new invention to tell me about.

"I've got a new theory about bike design," Ralph said, and I want to tell you about it."

"Funny thing, Ralph, I do too," I said. "Steepen the seat angle!" I declared.

"No!" said Ralph. "You're wrong! Move the bottom bracket back!"

I maintained over the years that we were saying precisely the same thing. Ralph maintained that we were not. Either way, we both came out with bikes that winter that had strikingly similar characteristics: a steep seat angle and a pair of 650c wheels.

I felt confident that the wheels would not be a speed problem, because in roll-down tests and in watching how the girls raced on QR's existing dual 650c bikes the wheels seemed to be just as fast as 700c wheels. Indeed, Liz Downing took out a USCF license for her one and only career USCF race and broke the existing 40k time-trial national record for women: 54:00. (I'm quite sure that if she'd have given it a few tries she'd have been down in the 52s or perhaps even faster; Liz was one of multisport’s exceptional all-time athletes who is unfortunately not well-known among many of today’s racers).

The biggest difference between Ralph's bike and mine was the severity of the seat angle. We used 80-degrees, Ralph used 90-degrees. His bike was called the Desert Princess — named after the famous duathlon in Palm Springs — and was built by Holland Cycles. Our Quintana Roo was called the Superform, and we did not use the builders we had been using for our women's bikes. Our first prototype bikes — those with regular road geometry and smaller wheels (as described above) — were built by Joe Scriven, an R&D man in the Huffy factory. Our production builder was Rob Stowe at Phase-3 Cycles in Rochester, New York.

But our contractor for the Superform was Tom Teasdale, who built bikes in the middle of Iowa. His wife, Cathy Jo — painted them, and one of our trademarks was to have Cathy Jo paint every bike a different color. No two bikes were painted the same that year.

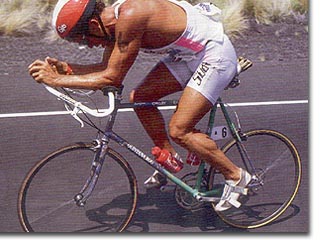

It is common knowledge among the old-timers in triathlon that the Superform first gained fame with Ray Browning's ride in the '87 Ironman New Zealand (pictured above left). But the first person to actually ride the bike in a race was John Gailson — he of Slowtwitch lunatic fame. Ray was the second person to ride it, and this was really our coming-out party.

Ray entered the race as a co-favorite, along with Tinley and New Zealand's champion Richard Wells. Ray showed up to the race and was roundly laughed at by his challengers. But he came off the bike 17-minutes in front of newcomer Matt Brick — who was later to prove himself one of multisport's all-time fastest cyclists and duathletes — and 30-minutes in front of Tinley and Wells. Browning smashed both the bike and overall course records.

Sales of QR’s bikes increased from there. Our biggest competitor in those early days was Kestrel. It was the first company to copy our design. In a way, though, it was the best thing that could have happened to us. It gave the geometry further legitimacy.

And that is the story of the first tri-bike.