A Week in Ecuador

The microcosm of travel is an apt metaphor for life itself. The later-fatal bicycle accident of one of the legends of the all endurance sport, Barbara Warren, during an August 2008 triathlon by necessity changed the plans of our small group of four traveling to the legendary Galapagos Islands in January 2009. With heavy hearts, Preston Drake, Angelika Drake (Barbara's twin sister) and I realigned our plans and found ourselves landing in the cold and unwelcoming metropolis of Quito at midnight. At 9300' (2850 m) elevation, this principal city in Ecuador sits nearly on the equator and features nearly year-round spring weather.

Our adventures began in earnest at the Quito airport where all 34 local taxi drivers bombarded us with offers of transport and happiness. Our bags were loaded into the van by somebody who turned out to have no connection with the taxi driver, taxi company, nor for that matter, anybody else knew why he was there. I thought that our midnight arrival allowed our skilled driver to ignore most of the red lights and used the white dashed line as a center guide. However, I found out during the rest of the trip that all drivers drive in a similar manner at all times of the day and night. Red lights are merely a "suggestion" in the same manner that makes a morgue director appreciative of the local driving habits for increased business.

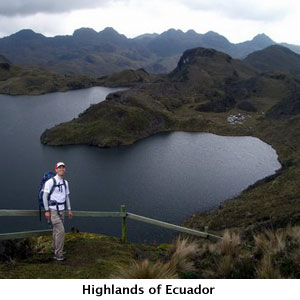

We began our trip in earnest the following morning, which dawned depressingly gloomy, a thick and unpleasant fog hung like dirty soot. As triathletes and adventure racers, however, we were able to endure the changeable weather. Jorgen, our Swedish-Ecuadorian guide broke with local traditions and showed up early, ready with a van and driver to tackle the traffic out of Quito. Descending through a historic neighbourhood on one of Quito's primary 2-lane roads, we were delighted to find that the local authorities had kindly installed massive speed bumps, for our safety and convenience, of which they provided neither. Our exit from the city brought us into a pastoral environment of vast sections of once-pristine countryside now featuring little more than an endless stretch of run-down shacks, closed shops, stray dogs, and the occasional working stoplight. Finally, really out of the city, the road improved and climbed up to a 13200' (4000 m) pass into and above some clouds. A damp chill kept us company as we expressed mutual glee upon observing another tourist group just beginning what would certainly be a cold and unpleasant descent towards the east and certain death in the jaws of some Amazonian piranha for those who failed to stop along the planned route. Our travels, however, took us on a turnoff and as we climbed up further along a mottled dirt road, our excitement grew. The clouds opened to extend our vista to both the east- the mysterious and dangerous Amazon basin, and to the west, and other peaks in and along the famous "Avenue of Volcanoes". Our ride ended at abrupt summit weighted heavily with radio antennas.

Finally able to escape the confines of the car, we hiked from this tall summit through high alpine fields of tundra-like flowers and boggy mud from recent rains. The four hour hike descended through a rolling terrain of ancient volcanic debris, past pristine lakes stocked with trout, and no man-made construction other than some basic trail features such as some rough steps. We met few other people, a sharp contrast to the bustling city of Quito, not far away. As fit triathletes, we made excellent time on the track, our guide thrilled to have a rare opportunity to break a sweat with his clients. An excellent surface for trail running, we instead opted for a hiking pace to enjoy the scenery, and to minimize the effects of altitude.

Angelika came up with an ingenious way to deal with the muddy descents, what quickly became known as the "ABS", for Angelika Butt Slide, or Angelika Braking System. Both Preston and I adopted this fine technique, obviously perfected by Angelika during her team’s win at the 1996 Raid Gauloises. No stranger to mud, our collective shoes and clothing bore the marks of a very fine hike indeed.

Our van picked us up at the lower end of the trail, some 3000' (900 m) below our starting point, and a short drive brought us to the Termas de Papallacta, world famous spa and hot springs. We enjoyed a selection of the 15 pools heated by natural thermal activity and sulfurous water. Supposedly therapeutic, we found the experience to be enjoyable and all-too-short. A sports massage and early dinner followed. The drive back to Quito became interesting rather quickly, as we discovered the 2-lane road busy with slow trucks with the alarming notion that keeping one's headlights off in the dark will save gas. Also, a significant rockslide earlier in the day remained strewn across this major road, unannounced in the dark (and likely unseen by said truck drivers), our van made a detour surprisingly close to the edge of the road, the mere thought of a railing decades away. We were more than pleased to return to Quito and excited by our impending departure to the wilds of the Galapagos Islands the following morning.

The voyage to the Galapagos Islands, located about 600 miles (1000 km) due east of the coastline of Ecuador, is generally a straightforward affair. The islands, 14 large and more than 120 smaller islands and rocks, the result of 4 million years of ongoing volcanic activity between tectonic plates, eerily similar to the Hawaiian Islands in remoteness, origin, and cost of a box of cereal. The most remarkably unknown aspect of the islands is their size, with 5 of the islands of significant size, for a total combined area of 4897 square miles (7880 sq. km), or about the size of the island of Hawaii and Maui combined. Thousands of plants and animals have made their way to the islands since their formation, some on the wings of nature, many more evolutionary variations, and others introduced to the (assumed) benefit of man. More on this later. The other remarkable aspect, for me at least, was the significant presence of human activity on several of the islands, complete with hotels and restaurants. However, with just 3% of the surface area zoned for human use, the vast tracts of land that form part of the Galapagos National Park are seemingly safe from harm, but human presence can be felt nevertheless.

In 1835 Captain Fitzroy and HMS Beagle visited Galapagos as part of a five-year voyage to make navigational charts for the Royal Navy. On board was a young, unknown naturalist named Charles Darwin. Darwin made extensive collections of the plants and animals and was struck by the fact that closely related species were found on different islands, although history shows that he didn't realise the significance at the time and in some cases failed to label his specimens with their island of origin. After many years of research and thought he published The Origin of Species in 1859, which put forward the concept of evolution by natural selection, a common theme throughout our journey.

Visiting the islands is best accomplished with a tour group due to their isolation, lack of public transport, and the simple fact that an educated naturalist guide is the difference, say, between a pile of rotten bananas and banana cake. Our group of 15, carefully organized by GAP Adventures (www.gapadventures.com), was a fairly representative cross-section of cultures and experiences, with solo travelers and couples from Canada, the USA, Australia, Great Britain, and a guide from New Zealand, spanning an age range from 18 to over 60. I quickly became friendly with most of the other participants, especially the Aussies, Gareth and Alex. Billed as an "adventure tour" with the corresponding stars for significant activity, the itinerary promised highlights such as mountain biking, kayaking, hiking, and snorkeling. I had traveled with GAP Adventures in 2003 for a tour of the jungles and highlands of Ecuador for their “Great Adventure People” TV show and felt confident in their professionalism and ability to cope with the uncertain travel issues that were sure to come up, plus with 1000 trips to over 100 countries each year, this is one company that knows travel, and were reasonably priced. According to the Galapagos Conservatory, half the visitors spend their nights on board a variety of tour boats while about 40% stay at hotels on the islands, with the remaining 10% visiting family and friends. During the first three months of 2009, there were 41,000 visitors to the Galapagos. Our tour was hotel based, with transit between and around the islands by boat.

Our first exposure to the Galapagos Islands were the official forms, immigration documents and visitor survey provided to us by the cheerful flight attendants on the TAME B737 en route. As I chewed on some unidentifiable poultry look-alike, I was delighted to see that the immigration officials provided space for exactly eight characters of my home city name; Of course no city's name is longer than 8 characters. And the same form allowed for 16 characters for the postal code. With a demented sense of humour, I tried to squeeze in more than 8 letters into the boxes. Somewhat amused and mostly shocked, I stared into the camera lens of a tourist, standing on the runway's end taking photos of our plane, mere meters from the idling engines. The fence around the airfield covering a handsome stretch of a few hundred feet around the terminal, leaving the rest of the runway as an on-site tourist attraction. When we arrived at the airport chaos, the form was gladly received as a formality and quickly disregarded. I was hoping at least to get a smile from the agent, undoubtedly that don't receive visitors from "Mt. Vesuvius" too often.

Things quickly got better as we began our tour of San Cristobal Island, one of two islands with an airport, the other being our fourth and last stop, Santa Cruz. The island town of Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, little more than a small and quaint "downtown" waterfront street, desolate except for the sound of barking. Expectantly looking for wild and savage stray dogs, my eyes followed my ears and settled on lounging sea lions, errantly scattered along the sidewalk, completely oblivious to the few pedestrians walking by. As we settled into our basic hotel, the adventurer in me wanted to immediately explore town, however, lunch was waiting nearby and a slight drizzle and hunger made for an easy choice.

It felt like we were at summer camp: 20 minutes after lunch (rice and fish, by the way, the first of many near-identical meals) we were told to get ready for a mountain bike ride. In the drizzle. On muddy roads. At least it was somewhat warm, and we were all game to get dirty. Our local guide mentioned a "5-mile" ride, which I began to think more appropriate as a run than a ride. While I tried to get out of riding, the downhill, or so I was told, ended on paved roads and was more like 10 miles (16 km). Still runable, but I acquiesced to fit in. Everybody did great on the mountain bikes, vintage 20th century, each with at least one working brake, some rubber on the tires, and no more than 2 spokes missing. Actually, the bikes were pretty decent, with only a few mechanical issues. The road was a mess, a muddy pothole-riddled surface, fortunately with little traffic other than some stray dogs (with barks that sounded unnervingly like sea lions) and some roosters. Our ride finished at an idyllic sandy beach and we were given a green light to go for a swim- with a catch. Our guide pointed out a huge barking sea lion, the beach alpha male, in shallow water surrounded by little pups. "Enter at the other end of the beach" our guide explained. "But if he comes over and starts barking at you, retire to safety and come out of the water wherever the beach master is not". We glanced at each other, our enthusiasm for the water waning slightly. We avoided the bark (and bite) of the protective father, and enjoyed a few circular laps of a quiet, protected bay. The water, of coldish pool temperature and clarity, provided our first glimpse of the incredible underwater life of the Galapagos Islands. Momentarily forgetting we were still on the lookout for the beach master, I nearly swam into a feeding turtle, then another. Some playful sea lions, of a much smaller and less threatening size, came by briefly to investigate our splashing. Tropical fish looked a bit out of place on the rocky bottom; only colourful coral was missing from a diver's dreamland. With a quick glance at the large form still swimming around in the same spot, we took leave of the water from the opposite end of the beach. Part of our group was huddled in a small circle, like a religious ceremony. Opening to reveal a tiny sea lion pup, leathery flippers taking leave of the sandy beach and stepping onto the feet of some of our group, teething with some gentle nips of the lucky guy's exposed and obviously very tasty-looking knees. Nope, not edible. But worth another try, and another, until a large female came over to let us know that we were likely a bad influence on her little pup. Park rules allow animals to interact with people if they choose to do so, but people cannot approach wildlife, a rule that fortunately appears to be widely respected.

Upon returning to the hotel, wet, dirty and tired, it seemed like a perfect opportunity to clean up. Woe is the poor sucker who steps into the shower, glances up to notice a larger shower head than usual. An understanding glance downwards highlights a single faucet knob: cold water. A reluctant glance back up confirms that in Ecuador, even a shower can be hazardous. An ungrounded 20 Amp, 250 V wire leads to the shower head from an exposed breaker. Gleaming copper contacts basked in the dull glow of the single naked light bulb. Consider for a moment that the death penalty by electrocution is carried out in select states in the USA by shocking the convicted felon with a jolt of 2450 V, so 250 V would provide a nasty shock, which if not fatal, would certainly make one late for dinner. Standing under a flow of tepid water, my hand shakes as I reach, fingers dripping, towards the small white box whose entire purpose in its inanimate life is to control the destiny of electricity to the shower head, or any other conducting material that happens to catch it’s fancy. My mind racing to a likely future of writhing on the ground, and just how fortuitous the construction of the water catch basin was designed not just to catch water. The breaker flipped and I braced for impact; One that fortunately never came. The only other side effect of cleaning up was to realize that the shower of mud from the bike ride was never going to completely come out of the previously-white running shirt I had so carefully chosen earlier in the day. I fell asleep, but not without first moving the bed gingerly away from the wall, and from an unpleasant accident in the hands of an innocent looking painted mermaid and her real giant conch waiting to fall off to impale my sleeping form.

The next day dawned much more hopeful, starting out with the realization that the little mermaid had kept a hold of her shell, and that the sun had come out. In the spirit of a triathlete, I went for an early run with Preston, into the Galapagos National Park trails just near town. Exploring, we found a beach replete with sea lions sprawled over the expanse, iguanas sunning themselves in the early morning rays, Frigate birds soaring overhead. We continued on the hiking trails, bouncing over the lava rocks in the trail as though military training through old tires. We came upon a concrete statue of Darwin, surrounded at his feet by his beloved iguana, tortoise and sea lion. Someone had placed a large paintbrush in Charlie's outstretched hand as a joke; His other hand held a copy of his notebook. To the top promontory, we spied Kicker rock where we were destined later today, and a nice view of town. We returned for breakfast, just as the others were rubbing sleep from their eyes.

The activity for the day was snorkeling at various locations around the island. Onto a small 16-passanger boat, the 20 of us found places to sit or stand. Our captain had mercifully provided life jackets, though some of us were pleased to know we could swim to shore if necessary. After the preview at the bay the prior day, we headed to a rocky outcrop where we immediately saw marine iguanas sunning on the rocks. Underwater, marine iguanas have evolved to feed: claws gripping the mossy rocks, eating algae and moss as though it was the most perfectly natural thing to do. Fish swam by, the iguanas undeterred. Some playful sea lion pups, knowing the iguanas made fine catch toys, clearly made a point of grabbing the slippery reptile by its tail, then playfully shaking the poor creature, ready to toss it to another sea lion for a friendly game of catch. One can only surmise what may be going on inside the brain of the iguana during this humiliating game, most of which probably had a lot to do with finishing its algae meal. Some rays undulated by, unconcerned that their antipodean relative caused great shock and grief to the wild kingdom community with the untimely death of Steve Irwin in 2006.

The boat moved on to Kicker rock, so named because of it's shape from a distance of a foot and ball, the two separated by a sheer chasm of about 60' (18 m) deep water. The rest of the rock sits in 300' (90 m) deep ocean. Dropped like corks on one side of the split rock, the current carried us through the chasm, snorkeling above white-tipped sharks and rays (sting ray and bat rays). While we were told that the sharks tend to be uninterested in humans, we were also told to keep our distance, and not surprisingly, none of our group needed to be told twice. Then as some swimmers including myself began to warm up on board the boat, a few lucky ones including Preston saw the elusive and frighteningly dangerous hammerhead shark far below the surface, in relative safety from the prying fingers of foreigners.

The next morning dawned clear and I took advantage of some pre-breakfast free time (while everybody else was sleeping) to do some exploring by way of a training run. Taking the only road out of town, reversing our mountain biking route, I woke several dogs whose startled barks quickly faded: unlike dogs in mainland Ecuador, the dogs in the Galapagos were as friendly and unperturbed by humans as the rest of the animals. I was surprised to see four other joggers along the route, exceeding by about 4 the number of joggers braving the streets of the capital city of Quito at the same time, despite the huge difference in population. The uniqueness of the Galapagos continued to unfurl. A hearty breakfast followed (eggs are popular as domestic chickens are plentiful, but curiously, chicken for eating is not), but the comfort was short-lived as next on the schedule was a boat ride from hell, 2.5 hours of non-stop fun. Due to the lack of fuel on our next island destination, and servicing of the only boat fuel station on the following island, the boat's captain has lashed four large and leaking plastic fuel drums to the front of the boat in order to have enough fuel to return the empty boat to the island later in the week. As though a Hollywood set, ready to burst into a spectacular display of flames and terror, each drum cap was delicately screwed over a film of food grade plastic wrap which had undoubtedly turned to mush the moment it touched the fuel. Gasoline fumes wafted from the bow, exhaust eddied in from the stern, humidity and mold emanated from inside the lower deck, and someone's breakfast spilled with depressing reality over the port side. Like a dog breathing fresh air out a car window, I spent the bulk of the trip with my head out the starboard panel off the top level of the craft. One compensating virtue is that I got to see a strikingly large ray jump and flip out of the water twice in open seas, likely trying to remove parasites from its large winged surface.

In an effort to neutralize the nausea and discomfort from the trip over to Floreana Island, we stopped along the way at a small island and were given another chance to go snorkeling. Never a dull moment, I was assaulted by a sea lion, playing dare, nearly resulting in a head-on collision. Reminding myself that the sea lions are more at home in the water than I am, I made a mental note to attempt a similar maneuver at the next Master's swim class. Also underwater, our guide pointed and said "There's another white-tipped shark", said with about as much shock as if he had just said "Oh, there's another McDonald's". A strange land indeed.

In the 1930's, the island of Floreana was a life-is-stranger-than-fiction setting for drama and mystery. As described in a brochure that remains unavailable locally: "A German dentist and his mistress, a young family (the Wittmer family who still live on the island) and a self-styled baroness with three men came to settle in the island. Shortly after the baroness and her lovers arrived chaos began. They terrorized the other inhabitants while planning to build a luxury hotel. Eventually the baroness, her two lovers and the dentist all turned up missing or dead." One of the lovers was allegedly poisoned by eating tainted chicken, provided by the Wittmer family, who to this day, runs the only hotel and restaurant on the island, and whose hospitality we were able to receive. Iguanas greeted us, our first view of the colourful male marine iguana of Floreana Island, both larger and brighter than related species on other islands. Our bags were transported to the settlement of Puerto Velasco Ibarra by a 1930's era modified farm tractor to the only hotel, down the road, an oceanfront location that made up for any lack of creature comforts. One glance at the electric showerhead and I was more than delighted that it was hard-wired to the ceiling receptacle, with no breaker box in sight. We had a swim and relaxing time on the oceanfront patio and dinner at the only restaurant in town, run by the grand-daughter of Wittmer family. We had fish for dinner, thankful to avoid the chicken. The island's 60 or so inhabitants live a quiet and rural life surrounded by nature and solitude, and it was easy to see why foreigners landing at this site could be forgiven for entertaining the thought of building a luxury hotel. Fortunately, at least for Floreana, that threat has passed. For some of the other islands, however, tourists are increasingly loving the islands to death, and several island-wide conservation programs are underway.

Modern physics has spent centuries exploring some likely solutions to the classic 3-body problem that predicts the behavior of objects after a collision. What has taken years to discover was solved in an instant on an otherwise deserted road on the island of Floreana in the Galapagos Islands. On a sleepy early morning that wouldn't see another human awake for an hour, I was out running, having narrowly escaped attack by waking soon-to-be barking dogs, and I had just descended from the panoramic heights of an extinct volcanic cone when I was astonished to run into Preston, jogging uphill, at the same time as a bus from town came barreling past. Consider for a moment that on this island with not even 60 inhabitants and only 1 road, with once-a-day bus service, I can finally put into writing the solution to the 3-body problem, and state that after meeting, the 3 bodies continue on their merry way to their intended final destination. 300 years of physics has never provided such a concise solution! At elevation, the island was reminiscent of the Big Island of Hawaii- with raw lava along the drier coastline, and increasing vegetation at elevation due to higher levels of rain.

We returned from our training to a hearty breakfast, with pineapple grown and brought along from Santa Cruz Island, and the ever-present eggs. While our luggage made its way back to the boat by 1930's tractor and small boat tender, our group walked about a mile to a coastal spot often frequented by nursing sea lion pups, affectionately known as the "Loberia"- the nursery. It must have been recess as only a lone penguin stood sentinel, with the compensating virtue that it was quiet and we were able to enjoy the carpets of brightly red flowered vegetation, sesuvium (with this particular species found only in the Galapagos) and ocean views. The departure of our 18 person group meant the loss of over 20% of the island's population- infrastructure clearly not set up for larger groups or those who expect to eat chicken for dinner.

The 3 hour boat ride to the largest island of the Galapagos chain, Isabela, gave our group extraordinary views of a pod of Bryde’s whales. These rare beasts are mid-size whales, with an average length of 13 m and weigh at most 25 tonnes. These are not pets, and exist by virtue of eating prodigious amounts of food of pelagic schooling fish, such as anchovy, herring and sardine. We were also fortunate to be joined for several minutes by a pod of dolphins, playing in our bow wake and introducing what appeared to be a small family addition to the joys of wake surfing. The little dolphin, not more than 2' long and never far from its mother, was quite the star in this all-star cast. Thankfully, we broke up the voyage with a stop at Tortuga island- so named because of it's similarity to the shape of a turtle. The island was inhabited by vast numbers of nesting and mating pairs of the famed frigate birds, iguanas and sea lions. The frigate birds may well be earth's most pompas male display of attraction. They inflate their large red chest area to the point of near bursting, strutting for days and weeks for circling females to observe. During this extended courtship, their huge chests prevent the birds from feeding and a certain number of birds eventually die of starvation. The cliffs of this small island were filled with red spots, and clearly a lot of hungry birds.

Isabela Island was formed by the eruption overlap of six huge volcanoes (Alcedo, Cerro Azul, Darwin, Ecuador, Sierra Negra and Wolf) around one million years ago, though volcanic activity still persists on all but Ecuador, making it one of the most volcanically active places on earth. One of the most notable features of Isabela is the documented evolution of five separate species of wild tortoise (family Testudinidae), one living on each volcanic peak, the valley areas too rugged with lava for the species to intermix. These endemic species have been the subject of much research and a source of greater understanding of the origins of the islands and of species.

Scientists have found it useful to distinguish living organisms into a taxonomic structure of kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. First introduced by renowned Swedish scientist, Carolus Linnaeus in the 1740's, the placement of each organism- plant, animal, etc…in a giant tree has been helpful to understand the evolution of one species to another, and how some characteristics likely evolved due to environmental pressures or reproductive success. The oft-used phrase "Survival of the fittest" means that traits that enhance the survivability of a species are likely to be passed along to the next generation, while variation to unsuccessful traits will be less likely to survive the evolutionary process. The Galapagos Islands have provided scientists, starting with Charles Darwin's observations of the variation of the beak within 13 species of finch (a small unspectacular bird), with a living laboratory. The discovery of speciation of tortoise on a single island, physically separated by lava, has helped support the idea of specialized creatures with characteristics that enable successful survival in different conditions (moisture, food sources, terrain, predators, etc…).

There are three primary distinguishing categories of life related to evolution, introduction, and change. Due to the extreme isolation of the Galapagos Islands, the development of life on what began as raw, uninhabitable lava has generated several theories. The most widely accepted today is the idea that plant life originated from seeds and plants brought over by ocean currents as well as flown over by birds. Once they arrived, these life forms, identical to those on the mainland, began their evolutionary journey. Meanwhile, small rodents and reptiles likely came over living on masses of vegetation, and soon found a home on the islands. As this life began to exist on the islands, it could be described as "native", that is, native to a particular geographic area, such that the local conditions could sustain life of the species. Over thousands of years, as the native species began to evolve and change to the local conditions (consider the 5 tortoise species on Isabela), the species changed to such an extent that they now existed nowhere else on earth. Those species could then be called "endemic", that is, existing nowhere else on earth. Both endemic and native animals continue to exist on the Galapagos Islands. A third type of distinction exists, that is "introduced" where a particular organism is introduced from somewhere else and begins to inhabit an environment where it did not previously exist. Introduced organisms are considered to be introduced when brought over by human assistance, either as black rats were unwanted passengers in the holds of visiting ships, or as livestock that gained freedom. Either way, introduced animals have been a huge burden and threat to the native and endemic wildlife, taking over food sources, habitat, sunlight and nutrients from plants, or as predators to otherwise defenseless animals. Programs are underway for the eradication of unwanted introduced species and success has been found on several islands, though much work remains to be done.

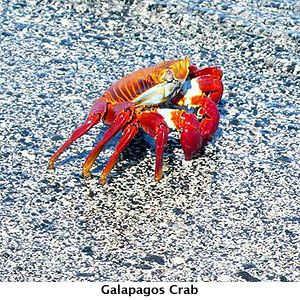

Back to Isabela island- the Puerto Villamil town streets are all sandy, the softest, finest, barefoot heaven kind of sand that could well be silk. With few vehicles and just a handful of streets in a grid pattern, navigating the town was an easy affair, and we quickly settled into our intimate hotel, a confusing collection of buildings and levels, a Y-split stair case, and a cozy dining area, but the star attraction by far was the collection of inviting hammocks scattered in the yard and on balconies. Our relaxation was short-lived, however, as we were ushered back to the cheerful port and onto two small fishing boats with belching two-stroke motors and not a bit of shade from the strong equatorial sun. A short ride past some rocks, penguins standing in line as if waiting for a bus, and over to a shark resting area, "Las Tintoreas". An offshore island with a naturally formed lava channel with two openings that are above the waterline at low tide, this trench has attracted sharks, in particular the white tipped variety, for eons. Without threat of predators, nefarious ocean currents or other dangers, the sharks enter at high tide and fall into a safe sleep during low tide, isolated from the rest of the sea. We peered carefully over the sides of the trench and spotted several sharks and not a few basking iguanas keeping the sharks company from above. A helpful sign indicated that swimming would probably not be a good idea. We continued on the island trail to a sea lion breeding beach, where we enjoyed the antics of a call and response of a newborn and its mother, surrounded by giant iguanas leaving curious tracks in the sand.

It's nearly a month after Christmas, and I'm told that the decorations around town, still shiny and fresh, should be down in time for their holiday of the Declaration of Independence of Quito in about six months time. Dogs gaze unimportantly at passing tourists, more intent on picking out fleas and ticks than on sampling your leg. The beach, a seemingly endless stretch of fine sand, beckons welcomingly. Finally after a busy day, we were given a chance to enjoy the sunset and dinner at our leisure along the waterfront, content to do both

Sunrise along the beach provided an opportunity to enjoy an active circuit training of beach running, swimming, crunches and pushups. I was fortunate to be accompanied by Alex, my Aussie roommate for the trip's duration, trying to work off some of the previous night's libations. The fine sand, while a delight to run and play in, also found its way into everything, impossible to shake off, I found bits of sand weeks later back in California. Back in time for breakfast, we were then asked to make sandwiches for a brown bag lunch. What, may I ask, prompted me to make a cheese, peanut butter, cucumber sandwich? Yuck!

Today brought our group to the more difficult trek of the voyage. A 40 min bus ride, flat through dusty lowlands, then up and up to 2700' (900m) elevation, in about 12 miles (20 km). It turned cooler, more humid, and with nice views of the coastline. We hiked up about 35 minutes to the rim of Sierra Negra, and to the precipice of the second largest caldera in the world. On the way, we spotted a rare Vermilion Flycatcher, a red-chested bird. Very impressive, but best was yet to come. A long 5 km hike along the east rim, a 200 m drop-off into a lava pit (red hot in 2005) on our left, and lush vegetation flourished on our right. After a short rest stop for lunch under a non-native tree, out of place in the otherwise low vegetation, the best part of the hike was onto Volcan “Chico”. The year 1979 brought the last eruption there, but it seemed very fresh. Still steaming fumaroles too, toxic gases of some holes creating a death zone around the hole while others generating steam help sustain the life of a small collection of ferns. Chewing up the soles of running shoes, we followed a track through the lava fields, past lava tubes and formations, broken over time, to the terminal overlook. The area was very reminiscent of the Volcano National Park in Hawaii. Of this area, my guidebook helpfully writes "Don't get lost". The Volcano Sierra Negro is 1160 m (3805’) high. One might inquire why the National Geographic map, all the tourist maps and most guide books have the elevation quoted as 1460 m. Ecuador, you see, has countless examples where it's form over content. Apparently, so happy are they to be able to quote an elevation that the fact that the number is incorrect is of little consequence. From the trail's end, I then began the 10 km run back to our bus, restocking on water under the tree, then along the ridge to more water at our bus and the ranger station. Feeling pleased with the progress, I decided to continue running downhill, allowing for the bus to catch me on the way to town, a plan I had made previously with the guide, who took this request with a mixture of surprise and pity. I picked up speed and motivation, running mental calculations in my head when the bus would catch me en route, and came to the conclusion that I was under-prepared with no food and but one jug of water. The first section was beautiful, lush, cool, and with a bit of rain, so I kept an easy pace, just cruising. I began to feel a bit fatigued and a bit hungry, so I picked up what I thought was a passion fruit. Keeping it safe until I came upon a road work crew, I asked, in broken Spanish, a bewildered worker who had followed my progress down the otherwise deserted road, if the fruit were safe to eat. He indicated "Si!" and as I jogged back to the open road, I enjoyed some of the most sensational passion fruit I've ever tasted. A rustling in the woods, and I spotted a black rat- yikes! An introduced species, I wondered aloud if I should catch it? Report it? I decided that a photo would be best. There was some traffic, not much, and it took a while before vehicles with some other hiker groups passed me….whom I had passed on the trail long before! They cheered me along from the open windows. I picked up another fuzzy fruit, a cross between a lemon and a kiwi, the exterior rigid Velcro fuzz, and asked yet another bewildered road worker if it were edible. This time, I got a strongly negative response, and happily tossed it back to the roadside. Back near sea level, the road was dry, dusty, and hot, where I ran out of water and began to suffer a bit, but I pressed onwards, caught between my ego of finishing this crazy endeavor and catching a ride from a passing vehicle. I was so certain that the bus would pass by any moment with respite! But the bus (that I had found out later had left the summit parking lot when I was only 15 minutes from town) had a flat tyre so when I got to the hotel in town, they arrived 35 minutes later, when I was already eating and relaxing in a hammock! What a great run, about 30 km from the trail's end, just under 3 hours in what turned out to be brutally hot conditions. I found out later that this route is rarely taken by pedestrians, but that ultra-runner extraordinaire Lisa Batchen-Smith had trained on the island, and had been known to run from town to the furthest trail and back, a distance of 60 km (36 miles)!

The workout done for the day, we spent a quiet afternoon with a rest and hydration, then a short trip to the beach to enjoy the sunset. It was a rough night: A goat in the yard behind our hotel was bleating during the night…and the roosters in the next yard over crowing all night too. As Alex said as he walked into the room after a night out "Shut up, you ****, it's just the friggin’ moon". Aptly said mate.

Several tortoise breeding and research centers are spread across the various Galapagos Islands. Successful reintroduction of tortoise species that had been seriously threatened by introduced species or human activity has been going on for several years, and while our time on Isabela was drawing to a close, we were fortunate to visit a tortoise nursery and breeding center. With over 800 tortoises from newborn to 30 or 40 years old, an awesome sight! Interestingly, the gender of the baby tortoise is determined by the incubation temperature, and equally critical is the vertical orientation of the egg as positioned by its mother. Eggs taken into incubation chambers are marked at the top of the egg so that they can be repositioned.

Playing peek-a-boo with a sea lion was not on my bucket list, but while the rest of the group got another bus tour, I decided to enjoy one more snorkel opportunity near the main pier area. A nice quiet spot, I saw a variety of sea life including a relaxed porcupine fish, tropical fish, a small stingray, and a turtle. I was minding my own business when I looked ahead and suddenly saw whiskers- a sea lion was coming straight at me as they love to do when playing. It hopped up on a rock, king of his tiny island, and I perched a few feet away leaning on an underwater rock. Undoubtedly looking like an alien through my mask, I lowered my head underwater and looked towards the sea lion, who copied my childish behavior. I came up for air, and the sea lion did the same. Several times we played the same game, though it tired of my infantine joy and perked up and swam away without looking back. While the sea lion went about its search for food and fun, I was left with an astonishing revelation and connection to the other creatures that share our world. The Galapagos Islands continue their magic and reveal to those who seek a greater understanding of the meaning of life and of our place in the world.

Our departure to the final Island on our tour, Santa Cruz, was bittersweet. Isabela had become a friendly home, by far the most endearing of the islands. The top-heavy boat we boarded for the two hour transit listed to starboard and bounced inharmoniously on the rough ocean. Just as we neared the port town of Puerto Ayora, our captain spotted a rare pod of Orcas, killer whales! For only the third time in more than four years, our tour guide pointed out the whales and the boat circled the area, gaining the curiosity of these huge and majestic creatures. Swimming under and alongside our small craft, one of the larger mammals rotated partially as it swam by, looking directly at the boat's occupants, all of whom were clawing over each other trying to get photographs. The boat, already top heavy, was now dangerously tilted towards the whales as most of the 18 people stood along the edge and on the top deck. Fortunately, we didn't tip over, although I had made a mental note of where the life jackets were stashed, and wondered what it would be like to swim with Orcas and if they were particularly hungry.

The most populous town in all of the Galapagos, Puerto Ayora was a bustling city and significantly busier and touristy than the other islands. Along the main street, a popular fish market drew a crowd. Unique to the Galapagos Islands, the fish innards are given to the pelicans and sea lions on the platform! Acting like an obedient dog with flippers, a "pet" sea lion gently rested its head on the cutting table, waiting for scraps. Tired of our diet of fish and rice for nearly every meal since Quito, and given the choice of dozens of restaurants, we opted for pizza and an evening on the town, without our pet sea lion.

The following morning I went for a pre-breakfast run out to Tortuga bay- turtle bay, reached by what was certainly a backbreaking project to create a 2 km long stone path. Gently following the undulating land through protected coastal shrubs, the tripping hazard the only distraction from the scenery. At the start of the path, a guard house is manned for 15 hours a day (the path is locked at night). The registration book I was forced to sign is hilarious…form over content, and I added my name to what became three pages of names by the end of the day, and a fine example of a bureaucratic waste of resources. The path finally ended at a magical beach, stretching a distance in both directions and nearly desolate, just a few other joggers enjoying the sunrise, and a host of iguanas on the rocks and sand. Intending to capture the magical moment and a cooperative iguana, I positioned my digital camera on a rock with the self-timer. Unfortunately, the camera toppled over and took a swim in a small pool of salt water the tide had left in front of the rock, putting a swift and unfair end to the camera's life. It had lived several productive years and earned its place in the electronic hall of fame.

Back in town, we enjoyed a hearty breakfast, cereal and chocolate coffee, the best yet. The jewel of all Galapagos research and breeding centers, The Darwin Research Center was our next destination. While I felt they could have provided a much better tour experience and better exhibits, the center featured nice enclosures and heaps of tortoises, many enjoying a feat of their favorite food, the Galapagos Opuntia (Prickly Pear). Rescued from the volcanic turmoil of the Pinta Island volcano, we saw the last known individual of the Pinta Island Tortoise, affectionately known as "Lonesome George". Like the carrier pigeon and the dodo, here was the very last individual of a species. Unlikely to reproduce due to both his increasing age and continued lack of a mate of the same species, it was sad and somewhat creepy to see the very last of a species. The research center informed us that prior to human settlement on the Islands, there were over 250,000 individuals (14 species of tortoise) while at present there are an estimated 20,000 individuals (11 species), all are endemic. As tortoises can live for over a year without food or water, they were kept by passing seafaring sorts in the 19th and 20th centuries in the holds of ships as a source of fresh meat. The slow-moving defenseless creatures were decimated in just a few decades. As one story goes, there were so many empty tortoise shells on one island that the locals used them to line the edges of their roads in town. We also encountered a tortoise named Diego, repatriated to the Galapagos from the San Diego Zoo in 1977. Due to ongoing volcanic activity on the island of Española, Diego is playing a significant role in the breeding program at the Charles Darwin Research Station to bring the Española species back from near extinction. The last 12 females and 2 males were rescued from that island, and Diego has significantly added to the gene pool for that species. Fortunately, humans have begun to better understand the impact of past behaviour and while the road to recovery of the tortoise family is not assured, we are finally taking accountability for our actions.

The highlands of Santa Cruz Island are rainy and cooler, and we ventured onto private property to hike through a significant lava tube. Remains of the volcanic origins of the islands, lava tubes are formed when lava pouring downhill creates a solid cooled encasement surrounding a hot liquid flow. When the flow stops, the liquid lava continues to flow downwards by gravity, ultimately leaving an empty tube, often miles long, and in the case of this particular tube, as much as 15m tall. A very low section provided some measure of entertainment as one of the group's participants ended up stomach down in the mud, the same unfortunate person who had mistaken a fresh cow pie for a solid rock a day earlier on the volcano, with predictable results. After the lava tube, we donned rubber boots and headed out to the natural habitat of the Santa Cruz tortoise (on private land) and enjoyed the eating antics of these wild but docile creatures. Weighing in at over 300 pounds (135 kg), adult tortoises eat vast amounts of grass and vegetation. Standing but a few feet away, it was clear these reptiles were much more skittish and shy than their relatives living at the research station.

Back to Tortuga bay with the group, this time hiking and swimming, and a spectacular kayak around a quiet lagoon, peering into the clear water for wildlife under the scorching equatorial sun. Some other guy tried to rent a kayak and got in facing the wrong way. What a sight, as the women from the rental station stood on shore, holding a life vest in the air, as the guy turned around in his boat, her face stricken with an expression of mixed horror and amusement. Some body surfing and beach play, and finally the long walk back to town and to our last Galapagos dinner, one that was served on hot lava rocks- an interesting concept, though the fish and rice tasted the same.

The islands appear to live perpetually on a Saturday, except when it's Sunday, and the Church bells tolled nonstop this morning as choir sounds from each of several churches wafted in the air. I took an early morning walk alone through town and to explore the "La Ninfa" beach area, a quiet little quay over the water in a confined part of the harbor, the water green and undoubtedly polluted, but an idyllic setting for some core work and yoga. After breakfast, we caught a bus for the 40 minute ride up and over the island volcano, into the clouds and down the other side, a terrain much more barren and dry. From a dock landing, we transitioned to an old barge that took us for a short trip across a small strait to the island of Baltra- formerly a US navel base- bombed to a flattened crisp in the 1940's- and now the home of the main airport, a 10 minute bus ride away. Small derelict structures and foundations scattered around the open fields- I can imagine the US military saying "and the pub over there…". The security screening was a joke- the metal detector wasn't even plugged in, and both x-ray machines were broken so a cursory inspection of our bags brought us into the lounge area to board our flight to Guayaquil, and then to Quito. The flight was uneventful except for a turbulent landing into Quito, with the fast descent to the high-elevation landing; I was more than a little pleased to be back on terra firma.

Shockingly, one of our group members out on a short errand to buy some fruit was walking alone in front of a major Western chain hotel was assaulted and mugged. While it was towards the end of the daylight, it was by no means dark and there were plenty of people around, all of whom disappeared the instant our companion began to scream. The assailants continued to beat her, with the aim of taking her belongings, which unfortunately included her wallet, passport and electronic book. Reporting the theft to the police afterwards, she got an inattentive response. Later in the evening, the hotel got a call from a stranger who "found the wallet and passport" and agreed to return it to the hotel, for a reward. The person actually showed up with the credit cards (all cancelled already) and some other papers but no passport. Apparently, this could be retrieved for an additional fee. What a racket- the Ecuadorian equivalent to blackmail, and it would appear that these people all work together, in close cooperation with the police. The following day in line at the Canadian Embassy, she met another five people who had also had passports stolen, just one day prior. My guide book warned of the dangers of travel in South America, and our group was now among the statistics. Fortunately, our friend was not seriously injured and she did obtain a new passport with some difficulty during the following days. One ancillary benefit of running through towns is that you are less likely to be assaulted and mugged, but the best advice is to follow that of most guide books: Leave valuables locked up, travel in groups, and avoid walking at night.

What a change the altitude can make, as the next morning dawned with a murderous sky. The view outside was far worse than depressing, a dark, foggy, and drizzly morning. In spite of the weather however, we continued with our plan to meet Gaby, a friend and one of but a few triathletes in town. Navigating crazy roads and traffic, exhaust spewing cars and trucks, and optional red lights, her father Carlos brought us safely to the base of the Telepherico cable car. A modern installation a bit out of place in the modest hillside shacks, the cable car brought us up to a literal and figurative breathtaking height of about 4100 m (13500'), through a cloud layer and to the grassy barren slopes of the Rucu Pinchincha volcano. We exited at the top station into a mixed fog with moving clouds, and much cooler than below, but still a comfortable temperature. Due to a combination of the fast altitude change and exposure to heaps of exhaust, Angelika had gotten an asthma cough and we ascended along a dirt path, muddy from an extended spell of recent rains. Some great vistas opened up down the city-sprawled valley, and up towards the peak towering above, at about 4800 m (15750’). Luckily we had no rain and we made decent progress, however after an hour of a cough getting progressively worse, Angelika wisely decided to turn back. As a reminder of the dangers of South America, and of big city areas in particular, Carlos proclaimed that it was unsafe for Preston and Angelika to descend alone, so he went with them and allowed Gaby and I to continue our ascent to the rocky base of Rucu, a bit below the summit and a nice spot to turn around. On our descent, we did see some questionable people hanging about, and Gaby entertained me with stories of tourists who had gone hiking, only to be assaulted and all their clothes and belongings taken en route. We met back up with the others at the top of the cable car and relaxed with a coffee amidst the swirling clouds and few tourists who had braved the mechanical ascent, only a fraction of whom had decided to climb more than a few minutes from the Telepherique exit. As we descended, the weather changed noticeably, back to dry and warm.

A visit to several triathlon and sport shops in town was an enlightening experience. Doors were equipped with buzzers for entry, bars on the windows, very limited stock, and astronomical prices on anything (everything really) imported. Those shops really make do with what they have; we are very lucky in North America, both for product availability and support, and even more so for safe and plentiful training opportunities.

Even though the official tour had ended the day prior, our entire group was still in Quito and we enjoyed one last get-together for a last supper. Comically, one of our party got targeted to have a huge glass of sticky sweet juice dropped on her lap- the rest of us stared in abject horror as the glass toppled in slow motion. The dinner was otherwise uneventful and after so many meals at restaurants, I was more than pleased at the idea of eating at home very soon.

The following morning, we took a cab to the airport. How many times do you think one would have to show a passport? Seven times from pre-check in security all the way to boarding the aircraft, a personal record. A bit like a race check in, we progressed through the airport stations, a modern facility that lay in sharp contrast to most of Quito, and located nearly downtown! Angelika and Preston flew with me as far as Atlanta, where they continued on to San Diego and I flew to Los Angeles after a brief sprint through the cavernous Atlanta airport.

What an amazing trip overall: Not “easy”, with the details, the moving targets that were our flight times changing pre-trip, and the hassles of travel in South America. However, playing peek-a-boo with a sea lion, watching the sun set over the equatorial line and walking amongst the giant tortoise were all extraordinary experiences. It is certainly a “do it once” kind of trip, worth the effort by anyone who can travel, at some point in their lives. We are fortunate to be fit enough to enjoy the outdoors, to explore, and to have good friends who are eager to travel. Having that ability is one thing; Taking advantage of that ability is another thing. Get out there and travel! Experience the world! Travel puts life in perspective. How else would we know how very lucky we are to live in California, a clean land of opportunity and promise? Wherever you live, you can seek out and find amazing opportunities to swim, bike, run and explore our largely unspoiled world. The Galapagos Islands are waiting for you.

This adventure trip journal is dedicated to the memory of Barbara Warren, an inspiring and towering personality within the multisport world and beyond. May her memory never be forgotten.