Riding the Angeles Crest on Deeper and Deeper

There’s a thread on our Reader Forum right now, entitled FLO 90 can’t use it. Our user writes, "No traffic, no wind and flat road and felt like I was going to dump the bike. Am I the only one? Probably should just sell and get the FLO 40. I use the FLO disc and race on it even with higher wind gusts no problem.”

No sir, you are not the only one. I took my bike and several sets of wheels, up to the top of Angeles Crest Highway, at 7,400’ above sea level, at a unique point where the wind sweeps over the crest from the Los Angeles basin and out to the Mojave Desert. I kept putting this test off, because if it was windy enough to do this test it was windy enough for me to be terrified riding down a high speed descent on deep front wheels. And I was a little bit terrified.

I, like you, ride typical loops I use for field trials. Do the loop enough, you generate more and more relevancy to your times, and your equipment used. The fastest times on my routes always include deep wheels. Sometimes there are winds when I ride and, really, even on windless days, on the flats, if trucks go by the deep front wheels take notice.

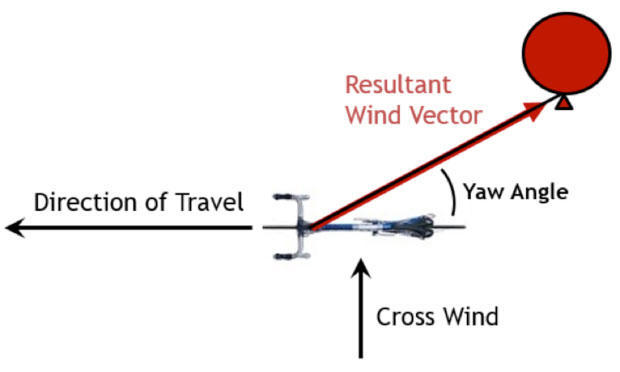

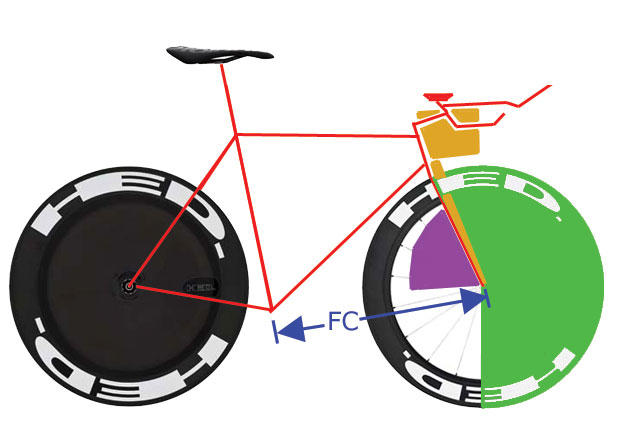

Taking the deep wheel off the back does not help (and adding the deep rear does not hurt). Note this user’s comment: "I use the FLO disc and race on it even with higher wind gusts no problem.” In my opinion, what matters most is what happens forward of the steer column. Changing what is attached to the steer column makes the larger difference. The wheel is the principle thing attached to the steer column. (The steer or steering column, or steerer tube, or just steerer, is the part of your fork that runs up through your frame’s head tube; the bike’s steering axis runs right through the steerer).

I took this Diamondback Andean up to the Angeles Crest, and you may think this bike is a bear in winds because of its massive surface area. But, not really. All of this surface area sits behind the steering axis. Changing the front wheels, that makes the difference. Riding my HED Jet 90 in the rear, or riding a disc in the rear, it doesn’t matter, the bike is fine.

From this point on the Crest the road goes down 3.5 miles in one direction and many miles in the other, so, I just had to pick a direction and go. The bike in the images above is fitted above with HED Jet 90s front and rear. Tactically, it’s simple. If I want to go fast I put these bad boys on. My fastest rides have been with either this HED wheel or a Bontrager Aeolus 9 on the front, and either a 90mm rear or a disc on the rear.

Just, I don’t ride these wheels on the front unless I’m confident that I’m not going to get pushed around by the wind. And here’s the insidious part: if it just gets too scary and nerve wracking, and you sit up with your hands on the pursuits, it not only gets slower, the handling gets worse. If you’re going to hike your leg over the top tube and head into the crossfire hurricane you’re pretty well committed to the aero position for best control.

The way out of this conundrum is just to have a second wheel with you. As long as your rear wheel is legal (discs aren’t always) the deeper the better and that’s the only wheel you need to bring to the race. On the front? Bring 2, if you’re unsure of the wind. Bear in mind that if the race has fast descents, these add an extra bit of pucker to a breezy day.

This test consisted of rides down a curvy mountain descent, 6 percent grade, with the road alternating north and south facing. It’s a breathtaking view, where you’re alternately looking down 7,000 feet on one side or 4,000 feet on the other. But this change of topography means the wind is unpredictable.

But, I had to get a sense of it. So down I rode, and then up I rode, where I switched the front wheel out for a Princeton Composites 6560 (on the front of the bike in the image above).

This is a new company, sort of a hoity toitier version of FLO. Like the Thornham brothers at FLO, the founders of Princeton Carbonworks decided that "great wheels were just too damn expensive.” But their wheels are not cheap, at the low-to-mid $2000s a pair. This wheel was a Princeton Carbonworks 6560 and, yes, before you say it, it bears a hard resemblance to the Sawtooth pattern on Zipp’s “5” instead of “0” series, the 858, 454 and so forth. Zipp’s idea is to give you the benefit of a deep wheel with better handling. I didn’t have one of those Zipps handy, whereas I did have one of these.

My second run down the hill was on this Princeton Carbonworks 6560 front, and I expected it to complain in the winds, around corners, so I was primed and ready to hair out. But it didn’t give me as much lip as the HED 90. But then, the 6560 is so-named because it’s 65mm at the nodes and 60mm in between. Of course it won’t talk back as much. But is it as fast as a 90mm wheel? This I don’t know. But it was slightly easier to handle.

The guys who make this wheel are all former Princeton rowers, so of course they know Jordan Rapp, also a former Princeton rower. This is how I met them. More on these guys and their wheels in a separate article.

Then I put a Rolf Prima Aries 6 on the front (pic above). This is a 60mm wheel and on this one I was reasonably confident descending on this wheel during this test. This is the depth of the wheel I’d buy if I only had one front wheel. It could be the second wheel I’d bring to a race. I raced a couple of weeks ago, on my HED 90s front and rear. Not a problem whatsoever. So, I don’t want to make a bigger deal of this than it is. Just, this Rolf Prima Aries 6, or an Aries 4, or a Zipp 404, or 454, or even taking my Zipp 303 off my gravel bike, switching out the tire and retasking it as my bail out front wheel for tri, all that is fair game when the wind picks up.

Lessons

Don’t worry about the surface area of your rear wheel causing you trouble. Worry about your front wheel causing you trouble.

Pick up a shallow front wheel somewhere along the way. If you’re going to take a deep front wheel to your race, take your shallow front as well, unless you know the course and the weather well enough that your deep front will certainly be fine.

Consider not only the winds, but the winds on any descents. The time you lose by having to slow down on descents is hard to make up elsewhere on the course because you have a 90mm front wheel instead of a 40mm wheel. Consider Cameron Wurf’s record smashing 4:12 bike ride in Kona this past year, on a front wheel that can’t have been deeper than 40mm. "There are barely any instances where you’ll find those super deep front wheels to be advantageous,” Wurf told us, "and certainly never in Kona. Choosing the front wheel was a common sense decision to us.” While I’m not so sure about Wurf’s aerodynamic knowledge on this (Wurf in Kona is pictured below), I am sure about his own capacity to parse between a wheel you can handle and a wheel that handles you.

If you own a 70mm or 90mm front wheel, train on it. It used to be considered wisest to train on training wheels and use your race wheels only for the race. Not anymore. Putting on a deep front wheel either speeds you up or slows you down, depending on whether you’re constantly in fear of getting bucked off during your race. It’s important you know how you and your bike are likely to react in conditions with which you’re unfamiliar. If you approach a windy descent not knowing if your bike is controllable at 40 or 45mph, you’ll hair out. You’ll put the brakes on and ride 25mph down that descent.

You need to experience every condition possible with that deep front wheel before you experience it on the race course, so that you have confidence in your ability to ride your equipment down that descent, and in the face of that sidewind. The advent of the deep wheel means my race wheels never come off my tri bike.

And finally, there are new wheels that I haven’t tried yet. I haven’t ridden Zipp’s Sawtooth wheels. I haven’t ridden HED’s Vanquish 6. It may well be that some of these new wheels give you the benefits of surface area and mitigate some of the handling liabilities.