Heart Rate Makes a Comeback

Written on the Slowtwitch Reader Forum in 2018: “Heart rate is only a surrogate for the power zone. It can be affected by hydration, fatigue, caffeine so it isn't as helpful as just training by the power zones determined by your FTP test.” That was one of many posts reflecting the mood of our readers. Heart rate was old school. That 15-year argument was won by the train-by-power folks (certainly in cycling, and even in running there’s a strong train-by-power contingent). If you were foolish to argue on behalf of HR somebody would post saying the 1980s called and wants its training method back. But…

That antiquated and vanquished arbiter of effort – heart rate – is rising from its grave.

The heart rate (HR) apologist would concede that heart rate is affected by temperature, humidity, fatigue, hydration. But that apologist would point precisely to this as the reason you use HR as a gauge of effort, in a workout and in a race. Heart rate is the absolute measure of fatigue. Not of power. And not of blood chemistry. But fatigue as measured by HR is a close analog to blood chemistry.

Here’s the converse to the power argument: HR is not derivative. It is not a contrivance. It does not need to be normalized for weather conditions. It does not need to be calibrated. It does not vary based on the quality of the tech and the manufacturer. And there’s another factor requiring normalizing of power, which we’ll get to. It isn’t as if athletes are throwing off power and rushing to heart rate. More like there’s a gradual reentry of HR into the training regimen, because power alone has occasionally led athletes to less-than-ideal outcomes.

“The metrics I currently use are power, HR, Moxy, lactate and RPE, wrote Lionel Sanders to me last week. “I would say they all have value if you are able to properly interpret the data. I did not wear HR for most of the early part of my career, but I now wish I did so that I could look back and interpret that data better. I still think power is excellent, and I use it every day in training. My screen that I use when riding (both intervals and easy) has three metrics: lap time, Moxy data, and lap average power. I don't really use HR much during practice, but I do log it and use after afterwards in analysis to get a better sense of what the intensity actually was, and my readiness and recovery level going in, and how stressful the session potentially was.”

“I think I’m probably in a bit of a transition,” wrote Taylor Knibb when I asked her. “I would say that I train a lot with power, to make sure I’m getting the right intensity and achieving the aim of the session. My new coach has me take lactate measurements and also looks at heart rate to confirm that.”

Looking at “heart rate to confirm” lactate measurements. What does that mean? We’ll get to that in a moment.

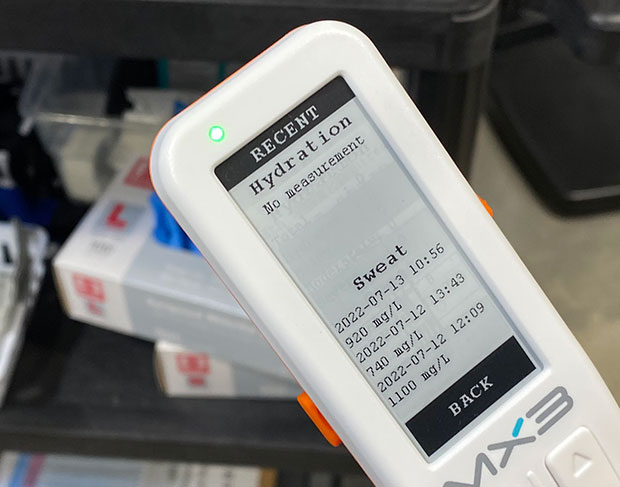

Lactate is for sure the hot metric right now for the highest-level athletes. But real-time lactate isn’t typically something an athlete uses during training all the time. You use it to establish your training zones, such as AT or MLSS (depending on the system you’re using). A lactate step test is not pleasant – neither the workout nor the 5 or so times you puncture your skin. Once that test is done you know your lactate threshold and the goal is to increase that threshold (the work you can do before your blood lactate increases beyond a certain point) which is also system dependent but is generally between 3 and 4 millimoles per liter. Now that you know your threshold your training program (of your choice) has you do X number of workouts at lactate threshold, Y number of workouts below that, and Z workouts above it.

But you aren’t measuring your lactate continuously during your training, so you use a proxy metric to tell you when you’re in the zone you want to train in. Heart rate or power is that proxy. The problem with power is that it is variable, depending on the platform and activity. By “platform” it’s your stationary smart trainer and any difference in power meter model across your bicycles. By activity it’s that your average power during (say) a mountain bike ride may be different than during a road bike ride if performing that ride inside a given zone is your goal.

Beyond that, challenging atmospheric conditions ratchet down your capacity to perform. We know this. Part of that is reflected in your lactate threshold, which is reduced as temperature goes up. Over the course of my reading it appears to be reduced as temperature goes down as well (due to vasoconstriction). The one arbiter that always tells the truth is HR, which is a reliable reflection of lactate accumulation. But HR is a little laggy. Still, it's laggy only by a few seconds and the literature thinks it's a close analog to lactate accumulation. In sciency terms the heart rate deflection point (HRDP) pretty reliably tracks with lactate threshold. You can actually figure out, on the cheap, what your lactate threshold is by paying attention and trying to identify your HRDP. There’s a protocol for this and you probably have heard of it. It’s the Conconi Test.

For some in triathlon who came from activities other than cycling heart rate remains an important, and perhaps preeminent, metric.

“To add some context to my thoughts I only started cycling in 2015 and 16 and was using power almost immediately,” wrote Kat Matthews to me. “However, I have been running since I was a child and training to heart rate. So, heart rate has always been my benchmark for everything, always reliable (especially in the early days of less reliable power meters).

“I do bias HR over power on most days, especially when training fatigue is heightened. I will always have power targets in mind but it is HR that controls the session, aerobic hours and higher intensity, e.g., I go into a session aiming for 320w in a HR range of 170-180 but if my HR is holding at 170 then I go harder and if it creeps above 180 I ease off, regardless of the rep power.”

“For aerobic [non-interval] rides I will have average HR showing on the computer as well as average power and again I will have a personal goal for power but if my HR creeps up too much I will ease off. The third factor I use is RPE, in a way to triangulate these [other two metrics]. In racing, all the above applies, the same as training.“

Lionel Sanders looks at HR after the workout, but power is preeminent during the workout. Kat Matthews looks at power during the workout but HR also, and HR is preeminent. Which is better? I don’t know. If you normalize your power number based on your HR, that argues for Kat’s approach.

Jordan Rapp splits the difference, relying on HR at low-intensity efforts and power for high-intensity workouts. "I'd say HR for low intensity and lactate for high intensity. And power is basically just there to serve as a proxy for lactate because it's really inconvenient to do lactate testing in the field.

"I do think heart rate has certainly come back into vogue. I mean, I never – literally, never – wore a heart rate monitor from 2005 until like 2014. And even when I did, it was kind of useless to me because I was so grounded in pace and power. But now I do care about heart rate more because I've come to see how it fills in some of the gaps.

One way to look at it might be to imagine your car’s engine. It produces X amount of horsepower. You can make it produce that horsepower by simply stepping on gas pedal and maybe your best visual gauge in your car’s cockpit is your turbocharger’s boost. You can drive around just looking at that boost number and step on the accelerator enough to keep that boost pressure at 20psi. But you also have gauges that reflect the stress on your engine. Lactate accumulation is your oil temperature. Heart rate is your coolant temperature. If you insist on training to your boost and ignore the temperature gauges outcomes are predictable and if it’s hot outside both your car and your body will overheat. Then your “boost” will go down regardless of how hard you mash on the pedal.

When real-time blood lactate measurements become ubiquitous in the endurance training world, HR will have a new metric with which to compete. Until then, if you ask the 1980s nicely it might let you use its training metric.