Cory Foulk’s wild rides

More often than not, Cory Foulk is the epitome of the triathlete who has chosen the road not taken. And that, to pay due homage to Robert Frost, has made all the difference. Part 2 of the Cory Foulk tales.

WHAT SPARKED THE BEACH CRUISER IRONMAN

In 1995, Foulk raced Ironman Hawaii. “The Queen K was as windy as it could get and a guy in front of me got a flat tire and I stopped to help him fix it. He was a nice guy from Austria who got upset because he could not change his tire. So I helped him and a marshal pulled over and threatened me with a penalty for giving outside aid.”

While that rule is clearly spelled out in the Ironman rule book for all to see, Foulk thought that circumstances merited a merciful judgment call. “We were like in 800th place,” said Cory. “I told him, ‘You gotta’ be joking!’ The wind was whipping and we were all covered in dried sweat while changing the tire. I risked the penalty and finished the job. But later, it gnawed at me. In the transition area, they were playing loud rock and roll and doing hyper kinda things. It seemed to be more like that guy from the 1980s, that Hollywood aerobics instructor — Richard Simmons – than the Ironman spirit I felt in the early days. All this ‘Rah rah, you can do it!’ thing going on was just uptight and high strung and it started me thinking: Maybe something could happen here to help change this? When I picked up my bike after the race I looked around the transition area and I saw there were bikes costing $10,000 or more. No old crazy metal tube bikes. Just all these sleek aero bikes.”

The next summer at the Keauhou half Ironman, Foulk won another Ironman slot in a close duel. After the race, he was talking with some friends and somebody mentioned how expensive triathlon equipment had become. “I said ‘I bet ya I could do the whole thing with $20 bucks worth of equipment,’" said Foulk. “And somebody called me on it. ‘You’re on! I bet ya $50.’”

“OK, let’s do it!”

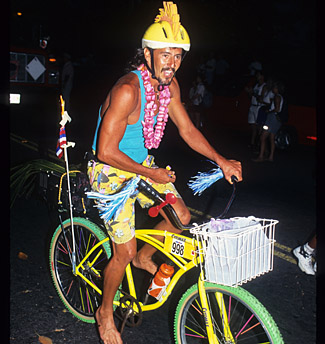

Foulk went to a local bike shop and they found an old rental beach bike in the back. He bought it for $15. “It was a 61-pound Schwinn Typhoon,” he said. “Every bit of it was rusty and corroded and the bottom bracket wheel bearings were shot. It was in terrible shape. I gave it a shot of WD30 on the heads so it would turn the chain. I cleaned it up and covered it with some cheap fluorescent green spray paint. And Iron Jeff from Champion Nutrition had just come out with Cytomax and he said he’d give me some decals for it. It had solid rubber tires which added to the weight. It did not coast well at all and it did not really roll unless I applied force. You had to pedal it — or it sat.”

Foulk started riding his lumbering steed 4 or 5 weeks before the race to make sure he could do it. “I wanted to make the cutoff, not make a fool of myself.” He said. He started his pre-ride at 4 AM because he didn’t want anyone to see him. “I rode to Hawi and came back on one of the downhills and pulled my feet off the pedals and put them in the basket on the front,” said Foulk. “Greg Welch was riding up to Hawi about 8:30 AM and he saw me and started laughing so hard he almost fell off as I rode by. When I made it back to town I thought ‘Yeah! This is makeable.’”

With a $20 limit for gear, he did not wear swim goggles and took some beat up old running shoes he could not in good conscience even give away and put them in the basket of the bike in case it was windy so could get off and push up the hills.

The bike had a kickstand on it. “It was real convenient,” recalls Foulk. “I will tell ya. I wish I had one on my Cervelo.” The tech officials asked if Foulk would take the kickstand off. He took a crescent wrench from the Schwinn’s basket and whipped it off and it passed inspection. “They gave me an M-dot Ironman sticker on it,” said Foulk. “Then someone came up and told me ‘You need to put the kickstand back on.’ My tires were too wide to go in the bike racks and they had no place for bikes like mine. So they had me park it right where the pros’ racks — near to Luc Van Lierde’s bike. It made for a really great transition. Honestly I do not think the race director thought I’d make it.”

THE RACE

So what was he trying to prove?

“I did Ironman Hawaii on a beach cruiser to see if I could finish the race on a 61-pound bike riding barefoot — which meant that you can’t pull up on the pedals, you can only push down,” he said. “Need I say it was not aero? Doing it on that bike was like doing it on a hand-powered Peterbilt truck. It was very, very difficult. Only at Mile 85 or 86 of the bike, after I had climbed to the top of the scenic overlook, did I know that I would make the cutoff.”

Near the end of the ride, Foulk had one little perfect moment. “On the old bike course, which finished at the Kona Surf Hotel, there was a steep, evil descent into T2,” he said. “Just before the descent, I saw a guy on an $8,000 Lotus bike in front of me. I knew I could not catch him on the flats. But I also knew without a doubt I’d catch him on the descent because my bike was so heavy, I had a big weight advantage. As soon as I got to the downhill, I knew the Schwinn would eat him, up and I passed the Lotus going into T2. That was really cool – for me.”

As it worked out, Foulk made the bike cutoff with little room to spare. He finished the bike in 8:50:21. With his 1:29:40 swim, he made the cutoff by 9 minutes 59 seconds.

“No shoes on the run either,” he said. “I ran barefoot. Honestly by nightfall, the pavement was not smoking hot.”

THE AFTERMATH

Foulk said there was a physical price to pay – but not where it was expected. “I had really horrible cramps,” he says. “And the next day I had a chiropractor crack my wrists back in place. Those high rise crazy beach handlebars put my wrists in a weird angle and it was made worse by no toe clips holding me down. But my legs were just fine.”

Foulk says there was some blowback after the race. “After the 1996 race, people told me that the front office said that I had made a mockery of their event,” said Foulk. “They sure gave me a lot more credit than was due. Honestly, the Ironman World Championship is an awful lot bigger than I am. It would be hard for one person to make a mockery of it. Of all the athletes I encountered afterward, from the elite to the age groupers, not one thought I was mocking them. Greg Welch almost fell of his bike laughing. He knew I wasn't a threat.”

Foulk said there was some lasting impact. “I believe it got under their skin that I finished,” he said. “So they made two new rules. Some people call them the Cory Rules. The first one was, No Beach Cruisers! It seems unimaginable they put this in words.”

Sure enough, in the 1997 Ironman Hawaii Rules and Regulations concerning the bike leg, item 13 had been added: “All participants are required to ride road/racing bikes. Mountain bikes, beach cruisers, and bikes with coaster-type brakes are prohibited.”

“Then they added another one,” said Cory. “‘Something about all athletes must wear appropriate footwear. Appropriate for whom? Now it’s too bad – barefoot running is making a resurgence.” In the 1997 Rules Applying to all Segments of the Race, number 12 was: “Other than the swim portion of the event, participants must wear appropriate upper body clothing and footwear at all times during the biker and run portion of the race.”

HIP TROUBLE

Foulk’s hip issues first came to light during the run at the 2001 Ironman South Africa in Cape Town. “I had a good swim and had a great bike but when I got off I could not run,” he recalls. “My right hip was in a huge amount of pain. It locked up, but it loosened up enough later to jog and finish the race. Afterwards, I went on a safari and had a great time. When I came back, I didn’t know what the hell it was all about. You limp around after an Ironman a lot of times, and it seemed to get better. Then a few months later I did the Keauhou half. I had a great bike, but when I got off I ran 3 miles and my leg locked up again/ This time I knew it was really a problem. That Monday I went to the doctor, had an X-ray and he said I had degenerative joint disease — avascular necrosis – in which the top of the femur collapses and dies. Floyd Landis had it. Adventure racer Robyn Benincasa had something like it – I think they called it advanced arthritis.”

From 2001 and 2005 Foulk switched entirely to long distance races because there was less impact. “I really focused on cycling, because I could not run.” He said. “I did a few Ironmans and some Ultraman, but basically I was reduced to a power walk thing. A physician who observed me told me that what I was doing was carefully placing one foot and jumping over it with the other for 52 miles. If you look at footage of me, I was just making the run cutoff and doing as well as I could with the bike. At Ironman Revisited in Honolulu (an Ironman distance event commemorating the 1978-1979-1980 Iron Man events on Oahu) [Scott] Tinley was doing the bike on relays. He could bike like the wind but could not run at all.”

Still, his hip woes did not stop him from taking on even greater challenges. When then-Ultraman owner Vito Bialla decided to try to do two consecutive Ultramans – the three day event that combines 6.2 miles swimming, 271 miles biking, and a 52.4 mile run – Cory was game to join him for the double. Foulk made it through the first unofficial Ultraman distance challenge within the time limits. Then he and Bialla took off the very next day on the regular Ultraman. Battling his hip, Foulk made it through 50 miles of the run on the final day before quitting – but found a rainbow in his failure to complete.

“I believe that was really great for me,” says Foulk. “I actually found exactly when Cory had had enough. I never found that line in the sand before. It was the coolest thing on earth to know that I was good at that point. I’ve had enough. I can go sit and have a beer with everyone else and know I am cool without wanting or needing to run to the finish.”

Foulk tried to wait until the procedure was approved in the USA, but by the spring of 2005, it still had not been approved. “So I went to Dr. Derek McMinn of Birmingham, England, who developed the procedure. He told me the two best places outside the U.S. to have it done were Belgium or India. I sent X-rays and asked the doctors that Derek recommended in each country what they thought. The one in Belgium said ‘Yeah, but it would take a long time.’ The doctor in India said ‘I believe you will run again, but I would have to prepare myself so I could race in 5 months! The doctor in India knew how runners and athletes think, so I decided he was the one for me. As it turned out, I didn’t race for 7 months. But only because there were no races I wanted to do for two months after it was ready.”

Foulk had a BHR [Birmingham Hip Resurfacing] on his right hip in December 2005. “The operation was done in India and it is really amazing the value you can get,” he said. .”I talked to the surgeon there and saw all the bills and since then I have advocated for hip patients to travel from the USA. Actually, the surgeon was paid a little more than an orthopedic surgeon is paid in the USA. But the rest of the cost is just 1/10th of what is charged in the USA. The operation cost $5,900. Travel was $1,000, and I paid $500 for a five-star hotel on either side of the operation. Without that operation, I’d be relegated to swimming. Since then I have finished 11 Ironman finishes and 7 Ultramans,”

Scott Tinley has had that same operation. “I talked to Tinley one time before he got his operation and told me he ran 100 miles a week for 20 years, so who cares about running? But the year after his BHR, he did the underwear run in Kona and told me, ‘I was lying. I miss running so much. Now I run 8 miles a day. I love it!’ “

For Foulk, the results have been spectacular. “In some way technically I'm running better than I have for 15 years,” he says. “I think surgery develops a strong joint, but the rehab part made me focus on technique and improving my weak points, like my looping stride. Now my stride is symmetrical and clean — as it should be.”

Foulk has a few ideas how he has lasted so long in his sport before and after the hip replacement. “I think it is a first a genetic thing,” he said. “I am biomechanically sound. I have a natural bone structure designed for running. I have run barefoot in training a lot and do not wear support shoes. I let my body take care of all the cushioning. I have a really good, mechanically neutral run. I do not land on the toe, not on the heel, but on the outside mid foot. I am a completely neutral runner.”

Foulk also says that triathlon’s three sport nature has helped him through the rough patches. “I listen to my body,” he says. “Triathlon is three sports – so you can just stop doing a sport when it is injured. It is not just about the run. If you have an injury and cannot run for 2-3 months you can bike. Where people lose longevity is when they insist on doing a set schedule of swim bike and run that day. Really, triathlon is designed for runners as an injury rotation and if you use it like that can do 7 age groups at Ironman. Ultimately, if I stay healthy, I will try to finish with 15 age groups at Ironman Hawaii.

THE FIXED GEAR IRONMAN

At this point in his life, no one who knows Foulk wonders why he sets up these seemingly unnecessary and brutal tests of his own grit and stamina. The answer is the same as voiced by the scorpion why, when he asked the frog to ferry him on his back across the river, did he fatally sting the frog halfway across and drown? “It’s my nature,” he replies.

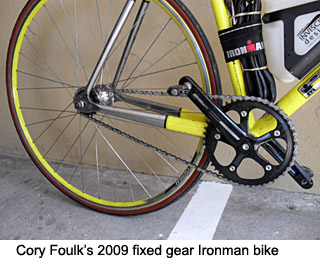

Foulk did Ironman Hawaii in 2009 on a fixed gear bike which he says was tougher than the beach cruiser despite some high end components like Zipp wheels on his strange hybrid steed. Perhaps sensitive to how his beach cruiser experiment affected Ironman officials back in 1996, this time Foulk did it in stealth fashion.

“I started with fixed gear Schwinn gears,” he said. “Then I put a 1080 Zipp for the front wheel and added aero bars because I wanted it to look like everybody else’s bike in 2009. I didn’t want to disturb the status quo this time. I wanted it to be a very personal experience.”

He said he disguised the fixed gear bike to look like a regular Ironman bike because “I wanted to not stand out, I wanted it to blend in with the whole group and make it a very personal experience.”

Foulk explains why finishing on the fixed gear bike was extraordinarily difficult. “The descents and downwind were much harder than the up hills.”

Why? “On a descent with a fixed gear bike you cannot stop pedaling. Whatever speed you descend at you must pedal that speed on that bike. If you are going 32 miles an hour your cadence is 200 per minute, So if you descend the hill back from Hawi and hit 40 mph, the pedal is revolving at almost 300 revolutions per minute.”

The beach cruiser, by contrast, could coast and literally freewheel. “It was a one speed bike that was heavy but could coast,” Foulk explained. “. “On a fixed gear bike the rear gear is hooked to pedals that always turned. When the bike wants to go fast on a downhill, you can only go as fast as you can turn the pedals. Man it was hard! I got to Hawi in 4:10 bike time — just about the time that Chris Lieto was getting to T2. And my legs hurt more than his. It was harder than the beach cruiser.”

Harder it may have been, but Foulk completed his 2009 Ironman Hawaii fixed gear bike split in 8:01:28, 48 minutes and 53 seconds faster than his 1996 bike. Added to his 1:43:07 swim in 2009, he had 45:25 to spare before the cutoff. After the strain of the bike, however, his run was much slower – 6:32:45 — and he hit the finish line in 16:34:35 – 47 minutes and 38 seconds slower than his beach cruiser marathon time.

NATURAL DISASTERS

When the Japanese earthquake and tsunami sent waves that hit Kona, Foulk was one of the fortunate ones. “My condo escaped the damage to our complex as though Moses was parting the Red Sea,” he said. “My place is on the ground floor of a beachfront condo complex with 30 units. The floor is just 10 feet above sea level and the tsunami that hit Kona was recorded at 16 feet. My neighbors’ units were completely ruined.”

Who do you thank for that?

“I have to thank God and the Hawaiian gods both,” he says. “Plus the fact that I volunteered for tsunami relief work in Banda Aceh in 2004 and 2005. I went there as an architect and environmental scientist to help them determine how to desalinate the soil and plant crops and grass and trees before the monsoon season came. The only thing left there was palm trees. All the buildings were gone. The regular trees were gone. But the palm trees were fine. So thought it would be a good idea to plant those same Areca palms in front of my condo. My neighbors’ furniture and doors and windows and walls were broken. But my palm trees stopped all of the destruction on my unit. The rooms were filled with water and eventually drained, but there was no real significant damage. We mopped it up and dried it out with towels.”

So what did he take away from his experience in the aftermath of the devastating Indonesian tsunami, and his much less severe brush with the recent tsunami?

“Where I volunteered, 58,000 people were drowned in Banda Aceh,” he said. “One minute they were on the beach, in school, at work — and the next they were just gone. In Japan it has to be a very, very similar thing. One minute they are driving to work, the next minute they are just gone. I think they are lucky that in Indonesia they live in a largely Buddhist culture where they believed in reincarnation and cycles. The wheel of time thing gives a degree of comfort and the belief to go on. But no matter what, the Indonesian tsunami is such a tragedy, a horror. Drowning like that, I can only imagine, would be the scariest way to go.”

And what did he learn?

“The lessons I learned are all about life,” he said. “If there is a lesson to come of that, it is the fact that in a heartbeat your whole life can change. So celebrate now. Every minute you have is an absolute blessing. So spend it wisely, or squander it. But spend it!”