WickWerks Review

I’m a geek-snob about only a few things. For one, tires. I don’t necessarily want a tire that is the ‘-est’ of anything (lightest, lowest rolling resistance, etc). It has to be a well-rounded package. There’s no logic in a super fast tire that flats halfway through the race. Another geek item is running shoes. Just in general – I can’t try enough of them. While my shoe collection hasn’t surpassed that of my wife (yet), I’m well on the way… and our closet is gasping for air.

But this article isn’t about tires or shoes. It’s about an even geekier, more nerdy topic – bicycle front shifting. Yes, I’m on the quest for the perfect shift.

What is the ‘perfect shift’? It’s dependent on a LOT of factors. Even if you have the perfect front derailleur, chain, and chainring, a poorly placed frame braze-on mount could screw everything up. There are necessarily a lot of cooks in this kitchen, which makes the problem more difficult, and perhaps unsolvable. This confluence of problems also makes a good shift that much more satisfying.

In this article, I review two sets of chainrings from WickWerks. Founded by Chris Wickliffe, this company has a very unique take on chainring technology. As a bonus, they’re entirely designed and manufactured in the good ‘ol US-of-A. I’d seen their rings used by the likes of many-time US National cyclocross champion, Katie Compton, and was eager to try them myself. Would they shift as-advertised? Could their technology really be that much better than everyone else? Let’s dive in.

Technology

Most modern chainrings rely on a series of machined ramps and riveted pins to aid in shifting from the small ring to the big ring. As well, most newer rings have teeth that do not all look the same. While they are spaced at a consistent interval (to match your chain’s pitch), the heights and profiles can differ significantly. Depending on what is done to the teeth, the shaping can aid in shifting up-and-on-to the big ring, and also accurately dumping down to the small ring. If you’ve ever spent any length of time speaking with a chainring engineer (I have), you quickly learn that this is one area of the bike that is half science, half art. Inevitably, the design process includes a lot of – tweak the design, manufacture prototype, test… tweak the design, manufacture prototype, test. It’s not unlike the development of frames and wheels using wind tunnel testing.

WickWerks’ take on shifting technology is very unique. They don’t use any pins at all (save the outer catch pin in case of outside derailment). Rather, they use a very aggressive system of ramps, which they call BRIDGE technology.

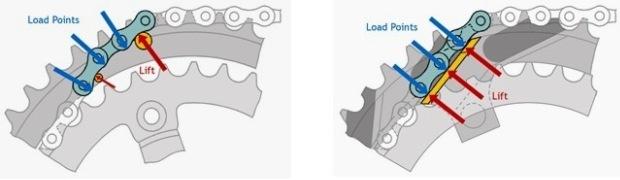

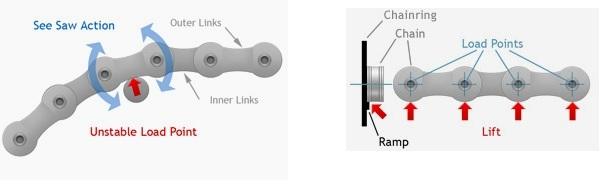

WickWerks provided some handy images to help explain how it works. The drawing below shows a standard ramp and pin system on the left, and the WickWerks system on the right:

They say that the BRIDGE technology spreads the load out over a much greater area, offering a quicker shift, and less chance that the chain will slip off and result in shift hesitation. Again, in the image below, a standard ring is on the left, and WickWerks is on the right:

The other obvious big difference is the fact that the ramps occur at much more frequent intervals than a normal ring. My WickWerks 44 tooth mountain bike ring, for example, has 11 of these large ramps. The idea is that you can shift at any point in the pedal stroke, and get a good shift every time. In contrast, a standard ring might only have two or three of these major shift points.

WickWerks rings have a surface finish that is different from your normal ring. I had the chance to meet with their head design engineer, Eldon Goates, to discuss this and the other features of their rings. In his own words:

“The anodize is ‘MIL Type 3 True Hard Anodize’. It's a military specification with lots of variations, but comes out much harder [than standard chainring anodize]. As you saw, the surface is much more resistant to scratching. What we have seen is the edges – like on the tips of the teeth – wear anyway, but the surfaces in the cylindrical area between the teeth that hold the chain tend to wear much longer before the teeth begin to have the elongation of typical wear out. How much longer? That's something very hard to quantify. We don't have the testing equipment to run rings a long time in a controlled environment (with salt or dirt or something) so we have only know what people are telling us – they last longer than other aluminum rings, but not as long as heavier steel rings.

A point to note: Anodize does NOT change the material strength, it only protects the very outside surfaces. Also, another thing we do (that I did not mention) – we do a final seal with a [PTFE] Teflon sealer. That puts Teflon in the microscopic pores of the anodize, and yet again improves the quiet and low resistance. The Teflon does wear off, but it's nice for the first few hundred miles.”

In our meeting, Eldon had me take a small flat blade screwdriver and scratch the back of a standard chainring – one that I brought with me, to avoid any parlor tricks or tomfoolery. The black surface scratched quite easily, revealing the shiny aluminum underneath. He then had me perform the same test on a WickWerks ring. In short, the anodize works; it only showed a small fraction of the scratch that the standard ring did.

Test Riding

After all of the tech talk, I was eager to install some of these rings and ride them. WickWerks provided me with two combinations:

50/34, 110BCD compact road, to be installed on a cyclocross bike with 10-speed drivetrain

44/33/22, 104/64 BCD standard mountain triple, to be installed on a mountain bike with 9-speed drivetrain (pictured below)

The mountain bike set was going on my snow-and-sand ‘fat bike’, which has an FSA Alpha aluminum crankset, a Shimano XT direct mount front derailleur, and a SRAM PC990 chain. The stock setup worked reasonably well, but was certainly nothing to write home about. It’s a mid-level crankset, with a reasonable price to match.

Here’s a look at the stock crank:

I installed the WickWerks ring using the stock chainring bolts. Here’s a shot of the new setup:

The next step was to re-mount the crank and check all of the derailleur settings – limit screws, height, angle, and cable tension. The only notable change I had to make was to raise the derailleur by about 1mm. Most derailleur manufacturers recommend a gap of 1 – 3mm between the top of the tallest teeth of the big ring, and the bottom of the lowest point on the derailleur cage. WickWerks recommends a range of 2 – 4mm. After fiddling with this and shifting a lot I found the best place to be here:

The clearance at the back of the cage (where my finger is) sits at 2mm, and it’s about 3mm towards the front. The cage is parallel to the rings.

How did it shift? Definitely better than stock. Upshifts and downshifts were faster and cleaner. I still was getting an occasional overshift to the big ring (where the chain climbs up on the teeth momentarily before settling down in to place), but no dropped chains. I rode it in this condition for several rides, including one particularly snowy and gritty ride. In short, the shifting was the best I’ve ever had in those conditions.

Similar to my other chainring tests, I wanted to try out different chains to see if that affected performance. After the initial tests with the SRAM 990, I tried a Wippermann 9SX. In my experience, Wippermann chains offer outstanding resistance to wear and breakage, but not always the cleanest shifting (they tend to be laterally stiffer than other chains). In this case, the reputation held up. Out of all the chains, this one had the greatest frequency of overshift:

Next, I tried a Shimano 9-speed HG chain. As I’ve come to expect over time, this chain offered the cleanest shifting. WickWerks does not require a specific chain for their rings, but mentioned that they’ve had the best success with Shimano. As it sits now, the bike functions better than it ever has before; the front shifting is really good.

Next up was the cyclocross bike. This bike started with a SRAM Rival compact 50/34 crank, Rival front derailleur, and SRAM 1091 chain.

Here is a shot of the stock crank:

With the new rings installed:

For this bike, I went straight to a new Shimano Ultegra 6700 chain. After the chain was on, I double checked the derailleur settings. In this case, I didn’t have to touch anything; height was already at 2mm of clearance between cage and ring, and the limits were dead-on.

If the mountain bike rings impressed me, the compact road 50/34 did one better. This combination, along with 52/36, are particularly difficult to pull off well. With a large 16 tooth jump from one ring to the next, you can get a tendency for clunky shifts, slow shifts, overshift, and a greater chance for dropped chains. With the WickWerks rings, shifting was fast, accurate, and all-around smooth. On either bike, I’ve yet to see a dropped chain on the outside or inside.

Weight and Price

There are a few things we’ve yet to mention, which could very likely make or break whether you decide these rings are right for you:

1. How much do they weigh?

2. What’s the price?

To the first, I’ll start by saying that I am not a big ‘weight weenie’. I generally want stuff that functions well before I worry about the weight. At first glance, these rings looked like they’d be heavy. They’re thick in all the right places – making them resist flex, but also adding weight.

What’s the verdict? While they weigh more than some of the weight weenie rings out there, they’re far from heavy. For comparison, a Dura Ace 7800 53/39 set weighs in at 142 grams; a WickWerks 53/39 set is marginally heavier at 149 grams.

That also brings up the discussion of price, and more importantly – value. A pair of WickWerks 53/39 road rings will cost you a very reasonable $139.50 for the set. This compares to $170 for a pair of Praxis Works road rings (another manufacturer of aftermarket upgrade chainrings). For Dura Ace, you’ll spend around $400. Dura Ace undoubtedly offers the best shifting out there – especially the incredible new 9000-series. It all depends on how much you’re willing to spend for that perfect shift. If price is no object, Dura Ace wins – and the folks at WickWerks will not argue that with you. At about 1/3rd of the price, however, I think WickWerks offers the best shift-for-your-dollar.

The main thing to understand is that chainrings wear out, just like your cassettes and chains do. It always kills me to see the folks who insist on buying the top-end gear, but then never want to replace parts. Even a Ferrari needs a new clutch every so often – despite the undoubtedly high cost. A $400 cassette or pair of chainrings can make a big dent in the ol’ wallet, no doubt. If you’re on a tight budget, consider buying drivetrain parts with lower-cost replacement parts. Your well-maintained ‘mid level’ parts will outperform a ‘top end’ piece of equipment that has been neglected.

How often should you replace those chainrings? Let’s assume you do the majority of your riding on a single bike, and train 12 hours per week. A conservative estimate is that you should put new rings on every 2 years, a new cassette on every year, and a new chain on every 6 months. This is, of course, dependent on conditions, how clean you keep your bike, and so on. If you’ve had the same bike for five years and never changed the rings, I assure you that the improved performance from a new set is well worth the investment.

Power Meters, 11-speed, and ring sizes

“Dear Mr. Bike Mechanic,

I have the latest and greatest gear, ‘cause I’m super fast, and everyone should know it. Will WickWerks rings work with my 11-speed drivetrain and crank-based power meter?”

Well, Fasty McGee, I’ve got some good news and bad news. First, the bad news. According to WickWerks, they cannot officially recommend their rings for 11-speed yet. However, they have heard field reports of success with 11-speed. The thing to note is they do NOT make any rings in the Campagnolo-specific 135mm bolt circle diameter (BCD). If you want to use their rings with a Campy 11 drivetrain, you must use a non-Campy 130mm BCD crank (i.e. FSA, Rotor, etc).

The good news is that you can use their rings with crank-based power meters (that I’m aware of). Quarq and SRM both require that the system be recalibrated with the new rings (or when you change between ANY different brand of ring). Not all chainrings are equal in terms of stiffness, and this affects the output reading. Of course, WickWerks rings are fully compatible with CycleOps Powertap hubs.

What about sizes? For road-specific applications, WickWerks currently offers 53/39 and 50/34. They also make a large variety of sizes for cyclocross and mountain bikes. Unfortunately, there are no big pie-plate sizes (54, 55, 56+) for you gear mashers and 650c riders.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this in-depth look at WickWerks’ chainrings. If you’ve tried them, we’d love to hear your comments below. I personally hope to see them expand their offerings in road and triathlon sizing – a market that may not always understand the workings of their bicycles, but can hugely benefit from reliable shifting.