Internal Gears and Belt Drive – In Your Future?

We talk a lot about bikes, gears, aerodynamics, and untold methods of optimizing these things to go faster. Specific to drivetrains, manufacturers continue to add more gears to the rear cassette – and sometimes remove them from the cranks up front. When I started cycling in earnest, 8-speed systems were commonplace (featuring 8 gears in the rear cassette and two or three chainrings up front). Soon after came 9-speed. And then 10. Today, most competition-level bikes are sold with 11 rear cogs… and everyone knows that 12-speed is coming in the next few years. Over the past few decades, manufacturers have typically added another gear every 7-10 years.

You might be wondering – why do we keep adding more gears? The cynic might say planned obsolescence and driving new sales. The optimist might say that each new gear adds a greater gearing range or optimized pedaling cadences afforded by tighter ratios – plus the obvious incremental improvements in weight and ergonomics.

Eventually, though, we’re going to run out of room. I don’t know where it will stop – 13-speed, 14-speed, or somewhere else – but eventually chains will become so thin as to be unreliable or too easily clogged with debris. Then what? How will drivetrains continue to evolve?

In this article, we’re going to investigate two likely candidates that might just be the next big thing:

1. Internal Gearing

2. Belt Drive Systems

Internal Gearing

The vast majority of road and triathlon bikes today feature external drivetrains. This means just what it sounds like – the derailleurs, cassette cogs, and chainrings are all attached to the frame but exposed to the elements. They’re mechanically efficient, but require regular cleaning and maintenance due to their lack of any protective covering.

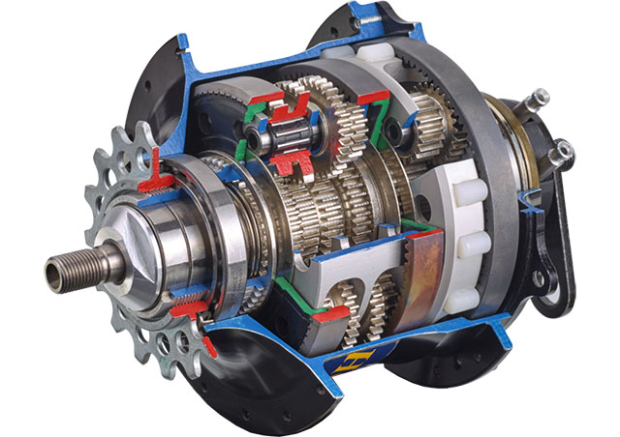

There is an entire alternative category of drivetrains, however, and that’s internal gearing. The “guts” of the system are typically housed either in the rear hub…

Above image © Rohloff

…or in a gearbox fitted into the frame near the bottom bracket:

Above image © Pinion

Generally speaking, both drivetrain types offer the same basic advantages. First, they’re typically well sealed and do not require any regular maintenance. Second, they’re quiet (though this can vary). Third, they afford extra ground clearance in off-road situations. Finally – and perhaps most important to performance-oriented cyclists – they open up a world of potential aerodynamic optimization.

That last one is a biggie, but unfortunately we haven’t seen much in the way of test data thus far. The problem is that frames must be made specifically for internal gearing. With essentially zero consumer demand nor a retailer network set up to support internal gearing en masse, there isn’t much motivation for a large frame manufacturer to create expensive test bikes with internal gears.

In addition, there are some fairly significant downsides to internal gearing – at least in their current state, and when applied to performance cycling. The two kay problems are 1) weight, and 2) drivetrain drag.

For more information, I inquired with Dan Towle of R&E Cycles, who are the largest builder of Rohloff-equipped internal gear hubs in the US. Rohloff is known as the current gold standard in internal gear hubs (IGH for short), with a reputation for stellar reliability and a huge gear range in their 14-speed system. According to Towle, about 10% of their bikes that go out the door feature an internal gear hub.

He writes, “We are the largest builder of Rohloff in the U.S. We sell a lot of Rohloff road bikes. If a standard road bike with Ultegra weighs in at 19 lbs (that's in the real world), a Rohloff built similarly in all other respects would come in around ~23-24. Although Rohloff claims it weighs in at standard weights of traditional components, they are comparing to the heaviest parts they can find. Ultegra is not that.”

Above image © Rohloff

Most cyclists will agree that adding four to five pounds to their bike is a less-than-desirable proposition. Surely it’s possible to minimize this penalty with careful (and expensive) component choices elsewhere on the bike, but that inherent weight penalty will need to be cut in half for serious competitive athletes to begin considering an IGH.

With respect to the additional drag caused by internal gear hubs, Towle commented,

“As far as efficiency of IGH vs. traditional gearing goes: There is an efficiency loss in a planetary gear system. My techy customers who ride both suggest that to be about 3% efficiency loss with Rohloff vs. their traditional gears.”

Part of the beauty of IGH systems is that they’re very well sealed from the elements. That, combined with their planetary gears and internal oil bath makes for extra drag. Personally, for a commuter bike or otherwise casual ride, a 3% loss is no big deal. I’ll take that all day. However, for the pointy end of the performance field where victory is often determined by fractions of a second, 3% is enough to cause a riot in the streets. Similar to the weight problem, this will need further development before it’s race-ready.

Belt Drive

What if you never had to lubricate or clean your chain ever again? What if the only maintenance required was an occasional rinse with a hose? What if there was a new drivetrain system that didn’t require any lube or grease – ending the days of black streaks on your right calf?

Such a system exists, and it’s called Gates Carbon Drive.

Above image © Shand

This is no ground-breaking scoop, since the Gates rubber company officially started selling their bicycle system in 2007. Based in Denver, CO with over 100 years of experience in automotive and industrial applications, Gates’ bicycle system centers around a polyurethane belt mated to special cogs. This system is still relatively new to the performance side of things, and many triathletes aren’t aware that the technology exists.

What are the benefits of such a system? As mentioned, there is essentially zero regular maintenance required. Belt drive systems are light weight, typically weighing less than an equivalent chain system. While the cost of a replacement belt is higher than a chain, they last twice as long or more.

What about downsides? For starters – and similar to internal gear hubs – a special frame is required. Because the belt is a continuous loop, the frame must have a split or opening to let the belt inside (typically at the right/rear dropout):

Above image © Huckleberry Bicycles

That’s not an absolute rule, as a new option has emerged from a company called Veer – with a split belt which allows the conversion of a standard frame.

Above image © Veer

Other downsides to belt drive systems include limited gearing, limited belt availability, and a loss in drivetrain efficiency. How much of a loss? Thus far, it’s unclear, but this article from BikeRadar in 2013 suggests that belt drive’s losses become less as the power input rises. Other sources and rumors have suggested somewhere in the neighborhood of a 1-2% loss.

While belt drive bikes started off as a single-speed-only application, they were soon mated with the first technology mentioned in this article – internal gear hubs. This allows the quiet and maintenance-free benefits of belts to be combined with the substantial gear range of an IGH.

In addition to their expertise and high sales of IGH-equipped bikes, R&E Cycles reported that about 25% of their IGH bikes are also equipped with belts. I asked what the biggest obstacles are, and Towle responded,

“Gearing restrictions are the main thing we run into. If someone wants to build in [the option] of changing the gearing around [later], there's very little versatility in the belt system when compared to the limitless options with chain drive. We have to build the chain stay lengths to support the specific belt/ring/pulley combination that gives them the range they want. To change that range, they cannot simply buy just any ring/belt/pulley and swap it out. The chain stay length has to support it.”

Above image © R&E Cycles

What this means is that you need to do your homework before buying. Thankfully, if you’re using the Rohloff 14-speed system, the total gear range is so wide that it reduces this issue. If you’re going single-speed-only, you want to be very sure that you buy the right parts.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The bike industry has to go somewhere, and it’s no easy feat to predict. What’s reasonably clear to me is that we’ll hit a wall in terms of how many rear cassette cogs we can fit into a standard drivetrain, and we’ll also hit an aerodynamic wall – which you could argue has already happened. The only solution I see is the internal gear hub. While belt drive systems don’t fit quite so easily into this mix, their lack-of-maintenance could be a boon for the average customer (plus I have to wonder the wattage cost of some seriously squeaky chains that I hear on a regular basis). I have a big itch to try a belt drive bike, and have a feeling one will make its way into my garage eventually.

Since this is an uncommon topic in the triathlon and performance world, I’d like to hear from you. What do you think of internal gearing and belt drive systems? If the weight and drag penalties can be cut in half (or more) – would you be interested? If you own a belt drive or IGH-equipped bike now, does the freedom from maintenance benefit you enough to recommend it to others?

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network