Speedland: The People

The People

It's impossible to discuss Speedland's shoes without first discussing its people. Kevin Fallon and Dave Dombrow have been designing and making shoes together for over twenty years. They have worked together at Nike, Under Armour, and – as they joke, the other German shoe company – Puma. They bring a unique perspective to footwear, and in speaking with them, I was immediately struck by how much of the Speedland ethos resonates so deeply with my own beliefs about the benefits of engineering-driven design.

We ended our interview with a simple statement that encapsulates the way Speedland approaches footwear. Engineering at its best allows you to just enjoy running.

To achieve this simplicity, they apply an unprecedented level of thought to literally every decision about every aspect of the shoes they build. But the practical aspect of development is paramount. They have their own YouTube show – Speedhacks – that offers insight in what they describe as their, "method of working." Speedhacks is the running version of Top Gear. And they think of themselves in similar terms. At the end of the day, they want to make something that someone can actually wear and actually run in.

And their approach is in-demand beyond what they can achieve with their own company. Speedland also runs a consultancy business – something (in what will become an obvious running theme… sorry… I had to) that is unique to this business. And they consult with a wide-range of businesses including HP (yes, the computer company…), Descente, Arc'teryx, Tracksmith, their old employer UnderArmour, and more. This consultancy stems both from their incredible expertise and unique perspective and also because they aren't really a competitor with … well, anyone. Speedland is absolutely focused on what they call hyper-performance trail and mountain shoes. They are – in their own words – obsessed. The vlogs on the decisions that went into each major "component" decision on their first shoe – the SL:PDX – reveals a singular passion for making shoes.

Especially given their history at major shoe brands, one never gets the sense that they want Speedland to follow the model of Hoka or ON in terms of becoming a major footwear brand. They remind me a lot of Lotus – another quirky, performance-obsessed brand that loves its niche and is happier playing in that niche than expanding beyond it to the mass market.

Shoes As Equipment

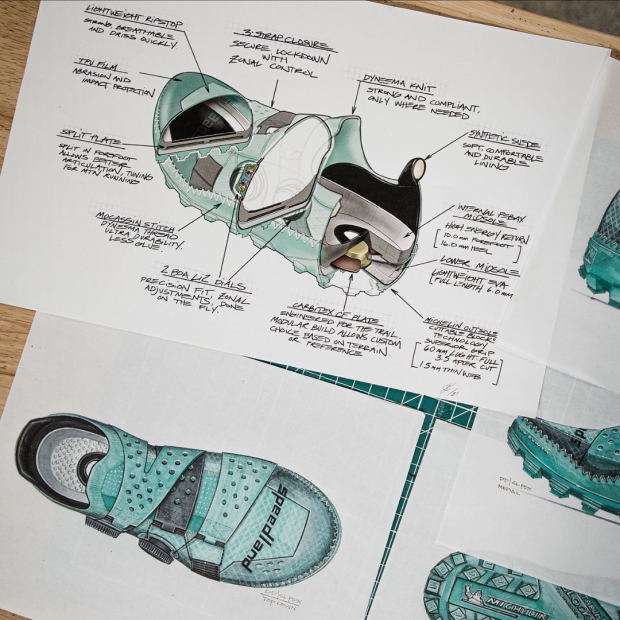

The shoes-as-equipment approach works, in particular, because good trail shoes are the result of such explicit choices. To a certain extent, all trail shoes are equipment. Lug patterns, in particular, matter a lot for terrain. But Speedland takes it beyond issues of simple traction. This is a bedrock philosophy for the brand. It's grounded in the belief that there is a right way – and a wrong way – to design and build a shoe. Kevin and Dave would like people to think of shoes – at least trail shoes – more like skiers and cyclists think about their gear. The closest analogy I have experienced is track cycling. Track bikes are highly-specialized, incredibly optimized pieces of equipment – or, more specifically, multiple pieces of equipment put together into a composite "thing" that we call a bike. Track bikes are a good analogy because there is a very clear limit on what's required. No brakes. No bottles. One chainring. One cog.

A shoe is similarly bound. Outsole. Midsole. Insole. Lacing system. Upper. And, nowadays anyway, plate. When you come up with an explicit set of requirements, you can then make careful, objective decisions about what each piece needs to do both individually and as part of the collective. As a quick glance at the pricing of Speedland's very small range of products will reveal, price is not a consideration. Though the price – while high – is no longer outrageous thanks to Nike readjusting everyone's perspective on what ultra-performance footwear actually costs.

Why Trail?

The high end road market is saturated. Because this is the mainstream, competition is higher. And so it's harder for a niche brand – however competent – to go up against the likes of Nike and ASICS. The road is also just simpler, and there is less clear opportunity for design influence. Trail lends itself more to explicit design. A shoe with a narrow profile where you *might* be more likely to roll your ankle might very well be a reasonable tradeoff on the road. But not on trails.

Likewise, the specifics of various trail conditions offer nearly limitless opportunities for optimization. Pavement is pavement. Asphalt and concrete are just not meaningfully different. But arid Southern California desert trails are dramatically different from the forested trails of the Pacific Northwest which are then massively different from the Deep South. Type of rock, type of dirt, type of mud, lack or likelihood of water, etc. All these conditions make a difference for trail shoes, in particular around outsole design. There is no single right tread. Likewise, the cushioning requirements on soft loamy trails might be very different than on rocky trails. Distances also vary much more widely on the trail. While there are notable ultras on the road – Badwater being likely the most iconic, most ultras take place off road. A shoe that's good enough for a road 10K is likely at least passable for a marathon. But a weight-optimized trail shoe for an equally short trail race will never be sufficient for a 100mi. The variety of distance and topography on trails just dwarfs what you see on the road.

Accordingly, trail running just lends itself to both interesting problems and also niche solutions to those problems in a way that road never could. What's the value of the rapid adjustment of a BOA lacing system as compared with a few extra grams of weight? How do you value lateral stability against overall weight? These are nuanced discussions without a single right answer, unlike on the road. High performance trail shoes are a reflection of the terrain, the designers, and the athlete who chooses them. And it's the way athletes make choices that inform the way that Speedland makes shoes.

The Athletes' Needs

Even though two-of-its-three (current) shoes are high-stack, ultra-focused shoes, Speedland is not an inherently high-stack brand. This is in obvious contrast to the brand that seems most similar – Hoka. At least, original Hoka – when it was still Hoka One One, and when it was still the niche creation of Nic Mermoud and Jean-Luc Diard. Their perspective as mountain athletes certainly influenced what they wanted Hoka to be. And in this way it's most obvious that Kevin and Dave's perspective primarily as designers accounts for a lot of the difference. Jean-Luc Diard is of course a designer as well, but ultimately Hoka seems to have been a response to what its founders wanted to wear, whereas the repeated line in my interview with Dave and Kevin was, "what do our athletes need?" The question they ask is, simply, "what would make THE BEST trail shoe?"

Initially, this was the SL:PDX, which is not a high-stack shoe. Because it wasn't meant for ultra-distance racing. It wasn't not meant for ultras, but it was more about traction and stability. And it was also about establishing what Speedland stood for. They wanted to, in their own words," do what we do." And, in doing so, "create a market." They wanted to show what was possible and to create a product – and an appetite – for shoes that represent the absolute pinnacle of design and execution for that very specific purpose.

Interestingly, they said footwear tends to move in seven year cycles. And they believe the era of high-stack, ultra-cushion, and carbon-plated shoes may end – or at least evolve and give way to something new, in the same way that minimalism gave way to high-stack. I'm less sure. I think the performance benefits of both carbon plates and high-energy return foam are too much of a paradigm shift. And, fundamentally, people just really do seem to prefer super-cush shoes that are obviously comfortable to minimal shoes that may or may not be more "natural" (whatever that means) and certainly don't – as the class action lawsuit against Vibram revealed – necessarily "strengthen your feet." But I also don't have nearly the perspective or history in this area that the Speedland founders do, and I'd definitely not bet against them. And certainly the pace of innovation in footwear is not slowing. We've now pretty clearly moved beyond EVA, and based simply on the embrace of new materials for both uppers and midsoles, I think that it's entirely reasonable to think that shoes may change again. There certainly are the first indications that maybe training in ultra-responsive carbon-plated shoes may not be optimal – thanks to Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience) for sharing the link to this research

We'll talk more about the carbon-plate – which is removable – in the follow-up article on the GS:TAM itself, but Speedland's design gives you a choice here, as well as allowing you to re-use this part of the shoe that won't wear out as fast as the rest of it. While they didn't build their shoes in this modular fashion because of this research, it did stem from the empirical data that is showing up along the same lines. Athletes like to be able to train without a plate.

Conclusion

I'll admit to an inherent fondness towards tinkerers like Kevin and Dave. People who not only enjoy thinking about how to solve interesting problems, but who go out and start tinkering with things in an attempt to actually apply that thinking in a practical way. As fantastic as their shoes are, I think that Speedhacks – their YouTube show – is their most important contribution. Along with their consulting, which allows the impact of their processes and approach to innovation to be larger than Speedland as a brand while also serving to grow it beyond what it could achieve simply through the sale of shoes.

But the shoes are, of course, the realization of all of this thinking. And they are superlative. The fit and finish is incredible. And the subtle innovations really do just make running more fun. I'll cover my adventures in the GS:TAM in a follow up, but I didn't think that piece would have made nearly as much sense without understanding the process that led that shoe to be the way it is. And I hope this provides that. I love the shoes. But I love everything that Speedland stands for as a brand even more.

Epilogue: The Bra Shoe

Even when they were at mainstream companies, Kevin and Dave were innovating. Me – "when were you guys at UnderArmour?" Kevin and Dave – "mid-2000s." Me – "were you there when Chris McCormack was sponsored? I remember UnderArmour came out with this crazy shoe where the upper was built to mimic the approach they took to making sports bras." Kevin and Dave – "yeah, that was us…"

UnderArmour never really made the sort of impact I think they were hoping in triathlon and, given the overall headwinds the brand faced around that time, it's impossible to know if this was just an idea that should have got more traction than it did or if it was just – like many trials – a neat idea that didn't really work out. It's more of a "the sports world is surprisingly small…" type of story that I think readers on this site, many of whom remember these various footnotes, will enjoy.

All photos © Speedland

[edit: an earlier version of this article misstated the Speedland's founders on the specifics of footwear cycles and their belief that era of high-stack, carbon-plated will end. We've edited the phrasing to better reflect their position.]

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network