The Blurred Lines Between Drop Bar Bikes

There’s been a reversal of polarity in road bike design. For 20 years, until year before last, there was a divergence among drop bar bike motifs. Trek, as an example, offered one dominant carbon road geometry 20 years ago. It found it needed another geometry, and then another (geometries it called H1, H2, and H3). Other companies followed suit and all of a sudden you could get any kind of road bike, in any geometric style, you wanted. You could get road bar suspension, disc brakes, aero versus road versus endurance, road versus gravel, the iterations were legion.

The one lasso that you could throw over all of this was the handlebar. These were all drop bar bikes (road bar bikes), but even then the divergence continued with handlebars. Now we have gravel bars and unique designs like the Coefficient bar, which has just furthered the divergence.

Then around 2018 we been to see a striking reversal. We are now in the middle of the great drop bar bike convergence. I believe what you’ll see by the end of this year is the lack of a clear distinction between road race, aero road, and endurance road. And by that I mean true endurance road, as opposed to badly misnamed endurance road, which I’ll get to.

Fit Geometries

There is in my parlance fit versus handling geometries. Let’s talk about fit geometries and by that I mean geometry relating to how the bike fits (rather than how it handles).

The great misnomer is that “endurance” geometry has anything to do with endurance cycling. Bikes like the Giant Defy (which Giant calls its “Endurance Road Bike”), and the Cannondale Synapse (“Endurance Race Geometry positions you forward enough to go hard but upright enough to go long”), are in the "endurance" category mostly because the “fit” geometry is upright. Higher stack, shorter reach. Imaging a rocking chair. As you rock forward, that’s race geometry. As you rock back, that’s “endurance” geometry. But if you ask people who ride really well (who are competitive at the highest levels), most will tell you there’s little to no difference between their fit coordinates whether road race, classics (the closest thing to endurance road as a use case), and gravel. Their position is their position, and if anything changes it’s the position while in the drops, which means frame geometry doesn’t change, only handlebar geometry.

“Endurance geometry” is pretty much what was “women’s geometry.” Each are examples of upright (narrow/tall) geometries, and each attached a false or misleading or unhelpful descriptor. Go to a USA Cycling road race and look at the bikes ridden by the women. Very few have “women’s” geometry bikes, if the women racing are buying their own bikes.

This geometry does actually have a place, but it has nothing to do with use or gender, but morphology. If you have long legs and a short torso your handlebars will be taller than someone your height but of average proportions (because you have long legs) and your bars will not be as far in front of the bottom bracket (if you have proportionally longer legs, you have a shorter torso). Simply put, your frame must have less reach, and more stack. If you are a road racer, fine, you need a road race bike but you may also need a higher front end. It won't place you upright. Your back angle will be the same. (And women are no more likely to need this geometry than men.)

So, what we really see, now, among the more thoughtful bike makers, is that “endurance” road does not have so-called “endurance” geometry. If you want your bike to fit most folks, build it to fit most folks. When Cervelo made the Caledonia, it didn’t hike up the front of the bike. It didn’t give that bike Barcalounger geometry. In fact, it smartly called this a Classics bike, not an Endurance bike. The R-Series pure road bike made by Cervelo, in size 56cm, has a stack and reach of 580mm and 387mm respectively. A Caledonia has that same stack and reach. This is fat-of-the-bell-curve performance geometry, whether for road, endurance, aero road or gravel.

Funny thing, the Cervelo’s Aspero (its gravel bike) in size 56cm is no higher in front, but it is a centimeter longer, with a stack and reach of 580mm x 397mm. This is marginally long and low even for road, and you see this geometry in the Canyon Aeroad, QR SRsix, and Cannondale SystemSix, all aero road bikes (though often in size-58cm on those aero road bikes).

Gearing

What we’ve always lacked was low enough gearing on our bikes. When I began cycling the low gear was 42×21 on a typical race bike. Over the last 45 years, as long as I’ve been cycling, the low gear on our road bikes has been getting lower, and lower, and lower, and lower.

You’re going to see this for road race, endurance road, classics road, and gravel. Why? Because gravel taught us all that if you put a lower gear on the bike you’ll use it. The convergent theme here is that all of these bikes are going to have gearing a lot more similar to each other than has been the case in the past. If you’re riding, say, 46×33 in the front, and 10-33 in the rear, your low gear is a 33×33, which is what we call a 1:1 (pronounced 1-to-1) ratio.

Why? Part of this is the expansion of available gears. When I began riding the cogset consisted of 5 years and now there are 12. You can add lower gears to the bike without expanding the steps between each gear (if you keep on adding additional cogs to the rear cluster).

Here is how this expresses itself, product-wise: Shimano’s GRX gravel groupset is a great groupset, but the gearing differences between this and its road groupsets will diminish. There just will not be short cage derailleurs anymore. A bicycle’s highest gear will continue to be between 125 and 130 gear inches, as it has been since the 1980s. It’s the low gear that’s changing. When I began racing, the lowest gear on my bike was a 54” gear, and that was very standard. When you have 1:1 gearing as your low gear, that’s a 27” gear. More and more bikes are going to come with a low gear between 23 and 28 inches, and it’s going to be that whether it’s road, classics, gravel, any bike that uses a drop bar regardless of use or road surface.

Front Center

I don’t know if you’ve been paying attention to this, but head angles are getting slacker. This is happening across drop bar platforms. In the bikes I’ve been riding, what you see are 72° head angles in both gravel and classics road (Cervelo Aspero and Caledonia), and even in aero road (Quintana Roo SRsix). You often (not always) find that this is coupled with an increase in fork offset to 50mm, rather than the typical 40mm or 43mm. This kicks the front wheel axle out in front of the bike a little bit more. Why? There’s probably a little more damping in the frame with that longer wheelbase and shallower head angle.

Another reason is that gravel bikes have a larger wheel (or tire) radius, if you put a 35mm, 38mm, 40mm or even 43mm tire on a 700c wheel. You need that extra front center (distance from the BB to the front wheel axle) to avoid shoe overlap. But even bikes that don’t anticipate the use of tires that big are increasing their front centers. You’re going to see this often, across bikes made in all drop bar motifs.

Tire Clearance

I was pleased to see that the Cervelo Caledonia very comfortably accepts a 32mm road tire. It can take at least a 34mm tire. But the new QR SRsix I just built can also take a 32mm road tire and that’s an aero road bike. I found this really interesting. To me, it follows the sort of thinking expressed in 3T’s gravel bikes. There is no reason – goes the thinking – that gravel bikes shouldn’t be aero, so, why not? Conversely, there’s no reason an aero bike can’t be ridden comfortably, and the best way to do this is not to hike the front of the bike up with “endurance” geometry, but just to allow the use of a more comfortable tire, i.e., a tire with more volume.

This is another area of convergence between these drop par motifs. Even if the bike is built as an aero road bike, these bikes are now often designed to be ridden with 30mm and 32mm tires, and a dozen years ago you were lucky if your standard road bike would fit a 26mm tire.

Hidden cables

Here’s what you’re going to see. Check that. Here’s what you’re going to not see: Cables. Hose. Housing. Increasingly you won’t see these on any drop bar bikes, and I include gravel in this.

There’s just too many good ways to hide hydraulic hose these days, so why not? Of course, this makes it a bear to change stems or handlebars, and even if there is some facility for removing headset spacers (through split spacers) you still have to take the hose out to miter down the steer column, if you find you want to lower your front end. I’ve been critical of this. However, in my personal use I counter this inconvenience with the use of in-line quick-connects. The one thing you have not seen – but I predict you will see – is the redesign of road handlebars specifically to allow the use of such a device. I think Cervelo is ahead of the pack already on this, with a handlebar with a cavity for the hydraulic hose, allowing it to run into the stem, but without ever entering the handlebar (image above). This handlebar is tailor made for a the use of a quick-connect.

Braking

This is pretty well a done deal, no? After all the sturm und drang of hydraulic disc brakes, they’re here, for every kind of bike, period.

Top tube bosses & GoPro Mounts

Top tube bosses, for a Bento, got popular in triathlon. Of course! It took a triathlete to recognize how monumentally dumb it is to carry your food around in your jersey pockets, if you don’t have to. Gravel bike makers noticed the utility of this, and began putting them on their bikes. So now you have tri bikes on one end of the spectrum, gravel on the other, and it’s only a matter of time before road bike makers put them on their bikes as well.

As you’ve seen in these pages with Cervelo, Form Mount and Zipp (pic above), stems and seat posts with GoPro style mounts for lights, radars, head units and cameras are here, and they’re here across all drop bar platforms.

Gravelish Handlebars

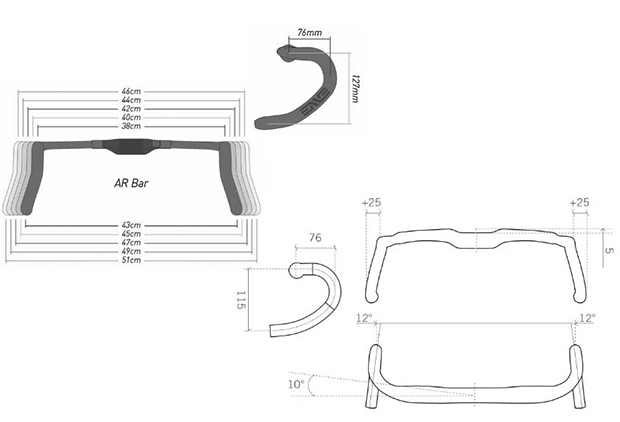

All the rage is the Coefficient handlebar. But as I wrote a couple of weeks ago, both road and gravel bikes are sharing geometries, for different reasons. I’ve got a gravel bar on my road bike I just built, but it’s got almost the exact geometry of a very popular road bar in the pro peloton. Their geometries are in the schematics below. This is another area of convergence. Road and gravel handlebars are becoming the same bar, for a lot of us. If that bar has a hoods position slightly narrower than you’re used to for your road bike, with drops slightly wider, that bar turns out to be both more aero and more comfortable.

The way to make a good “endurance” road bike – and I just prefer “classics” bike but whatever – is not to hike up the front end of the bike, but to make that bike comfortable for longer rides. Chop the front end, i.e., make a “chopper” out of the front end of the bike, by adding fork offset and slackening the head angle. Spec the bike with wheels that have larger inner bead diameters, and place larger tires on there. Apply what we learned from gravel handlebar design, and put comfortable thick, spongy handlebar tape on there. Put low gears on the bike, and place bosses on the top tube for food, so that we don't turn our bananas to mush with our kidney heat.

And then make it aero because… why not?

And this is what is getting done. These are the bikes in the pipeline. Classics, gravel, road race, aero road bikes are all using these design motifs, to one degree or another. Within a couple of months I’ll be able to present for your consideration an endurance road, a gravel, a road race, and an aero road bike, made by various companies, and assuming you put the same wheels and tires on them you won’t be able to discern very much meaningful difference between any of them.

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network