The case for wrenching

I remember emailing back and forth with Peter Reid in early 2001, who was at the time the world's best long course triathlete. He was telling me what a bike geek he was, and about his seven bikes he owns and all that.

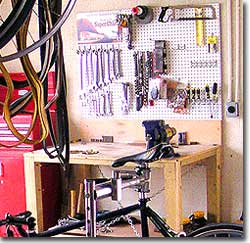

I felt the need to compensate so I told him about my tools. I told him that the real measure of a bike geek isn't in the bikes he owns, but in the tools he owns.

I don't know if I impressed Peter or not, but it was the best I could think of at the time. As for impressing anybody else, no illusions there. Many aspire to be the world's great practitioner of cycling; few to be the world's great mechanic in cycling.

But I always scratched my head at the fact that champion motorcycle racers could take their engines apart and put them back together again, and yet they still hired their own mechanics. Pro triathletes — as a group — are lucky if they can adjust their derailleurs. Pro cyclists are not much (if any) better. I used to travel to pro-infested races around the world, and would invariably be asked if I would work on one of their bikes. There was always a pro in trouble. I would often recognize my own handiwork, performed months earlier, and realized that I'd been the last person to do any work on that bike. The fact that there were so many pro mechanical DNFs in those races didn't surprise me.

I've got a million stories I could tell, but I don't want to embarrass anybody. Instead I'm going to show Slowtwitch readers, in serialized fashion, the tools I've got, and how to use them. I'm by no means a great mechanic. But I can keep a bike running smoothly, and the fact that I'm not a hot shot wrench ought to be of consolation to you, i.e., you can keep your bike running smoothly and reliably too.

This will be a never-ending series, since my quest to acquire tools will be a never-ending one (I've got to keep one step ahead of Peter). Before I start, let me share a story or two from those who’ve embarked on the road of bike repair and lived to tell about it. This, so that any of you who feel unequipped to work on your bikes will know that that's how most of us started.

Here's from Glen Spiller, co-founder (now retired from) Sinclair Imports, my own go-to U.S. based distributor. Glen says, in reply to a conversation we had during which I referenced "How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual of Step-by-Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot":

"Your story about The Idiots guide to VW's reminds me of the first job I got as a bicycle mechanic. It was at College Cycle in Oakland — long since gone — and Bruce Gordon was managing the store at the time, in 1971 or 1972. I had previously worked briefly in sales at Turin in Evanston, Illinois, when I first got out of high school, but I knew absolutely nothing about bicycle mechanics: had never built a wheel, or overhauled a bearing, and I could barely fake an assembly.

"Needless to say I had to exaggerate my mechanical skills to get the job. But when Elmer the cigar smoking owner hired me I immediately went to the University of California library and tried to memorize 'Anybody's Bike Book,' which you may remember, and was definitely to bicycle mechanics what 'The Idiots Guide' was to VW mechanics.

"I lasted about two weeks on the job before Bruce fired me for being so incompetent, but I gained enough experience during the two-week period to get an apprentice job at The Square Wheel in Berkeley and later at Velo Sport — and later returning to manage the Square Wheel. I was so in love with cycling and bicycles at the time, and I have been in the industry ever since."

I include Glen’s story because it reminds me so much of my own. I was running a wetsuit manufacturing company I owned, and knew very little about how to work on bikes. But, I wanted to build bikes, because I knew there was a better bike design out there that nobody else wanted to build. I found a welder and we were off and running.

What to do with the frames, though? Surely I would need some tools to chase the threads, face things, press this, pull that, and install all of the various bicycle specific parts. I had no more clue about all this than did my company's receptionist.

I called up a bike mechanic I knew at a bike shop, a guy who seemed pretty competent to me. I asked him for a list of every tool I might need. I ordered them, they arrived. I had a frame in front of me, and tools beside me. I held up each tool against the frame's various orifices until I found a match.

That’s how it started. I suppose I should’ve gotten Anybody’s Bike Book, but I was much too attention disordered for that.

In truth I can tell you that I ruined very few frames. None that I can remember, in fact. (Perhaps a fork or two).

Just think of it this way: What’s the worst that can happen?

If these stories don’t sway you, I still say go for it. Perhaps you might start smaller, working with tools that don’t interface with overly expensive parts. Change your own chain, for example, and your own stems, grease what needs grease, oil that which requires oil. And, of course, clean the darn thing. I’ve never heard of anybody damaging his or her frame with a rag.