What’s in a review?

This is a question that we get a lot, so I decided it was worth delving in to: “What goes in to a product review?”

More specifically – How does it work? Who decides what gets reviewed – Slowtwitch or the manufacturer? How long do you use each product before writing the review? Do you even use the product at all? How do you decide when to publish a review?

There are a million and one questions, so let’s start from the top.

Planning Content

The first thing we do before anything else is plan. We plan and plan (and plan)… and sometimes have to forget the plan. Normally I plan all tech content (reviews, etc) about three months ahead of time. Whatever you’re reading now at the end of August was likely conceived around the end of May. Some stories may be planned as far as a year in advance.

The reason we must plan so far ahead is that we cannot control one critical piece of the puzzle – when we receive responses from reps and manufacturers, and when product ships to us. The best companies have information and product in your hands within a matter of a few days; others could take months – or might never respond at all. When you want content to be published at very regular intervals (i.e. multiple times per week), a LOT of stories must be in the hopper at all times.

The reason that we must entirely forget the plan sometimes is that some of the best stories just happen. If a newsworthy item pops up right this instant, we must drop everything if we want to capture the story and publish something while it is still considered to be ‘news’. Journalism is not a career for those that can’t deal with interruptions. It is also not a career for those who demand 100% absolute perfection in every aspect of every word they write; it’s just not going to happen if you want to write enough to make a living. With our very small staff, there are no second, third, and fourth sets of eyes checking your work for you. Proofreading and fact checking gets done by a live audience of thousands (you).

Who comes up with the story ideas? While we do get a few that fall straight into our lap (as mentioned above), the vast majority of tech content must spring from our noggins, or those of our readers. If there is one value-add that we must provide, it is an ‘angle’. Some of our reviews involve products and companies that we approach out-of-the-blue. They may have never thought of their product as being useful for triathlon, or even know what Slowtwitch is. We may have grown into a big fish in the sea of triathlon, but we’re still a sardine in an ocean of worldwide sports.

The one non-negotiable rule we have with product reviews is this: If a manufacturer comes to us out of nowhere with a new request for a product review, we do not guarantee a review of the product. Full stop, no budging, and no strings attached. The reason is simple: We don’t know what the ‘story’ is yet. We cannot and will not tell a company, “Sure, send along your new widget that I have never heard of and know nothing about, and I can guarantee that I will publish a review within two months.” We need to get our hands on it, learn about it, and then determine whether there is sufficient ‘meat’ for a story.

Reviews are only useful insomuch that they can actually tell you something; that they offer a value-add. In a sense, we want to have a story to tell first, and the product is just a prop to tell that story. Sometimes we receive a product, spend time evaluating it and photographing it, and end up sending it back with no story. Usually this happens if we cannot get the technical information required to write the story that we want. In our world, product information is much more valuable than the product itself.

On the flip side, if we approach the manufacturer with a specific idea and request a specific product, we will guarantee an article. We already have the angle and want to pursue it. We do not, however, reveal the article format or pending content.

The best way to put it is like this. If I’m publishing three tech stories per week, that’s three new story ideas required each week, and at least three new conversations that must be started to obtain the necessary product and information. As such, I spend approximately 25% of my work week actually writing, and the remaining 75% on emails, phone calls, research, product installation, photography, and so on.

How long must you use a product before reviewing it?

How long do we use products? Or do we even use them at all? This entirely depends on what type of article we’re doing and the product we’re dealing with. With a standalone review of a single product, we use it as long as we feel necessary to make a fair evaluation. When you’ve done this long enough, you usually get a good feel of the product right out of the box and during the installation process. If it is a ‘preview’ article or something about a product that we physically cannot use (e.g. it is not available in the appropriate size or configuration that we personally need), we obviously will not use the product.

Whatever the product, we try to be as clear as possible as to A) Whether or not we personally used it, and B) How long the evaluation period was.

The evaluation process goes like this:

1) Receive product

2) Unbox it, check for shipping errors or damage

3) Photograph the product by itself. For example, wheels must first be photographed by themselves, before tires have been installed. Cycling shoes must be photographed without cleats, and before we’ve gotten them dirty. Both we and the manufacturers want to show the product in its original condition. Photography is always our biggest bottleneck, as it is often at the mercy of the weather.

3a) Edit, crop, and watermark all photos.

4) Measure and/or weigh the product. If the rim width is listed at 25.0mm but it really measures 24.8mm, we want to tell you about it. If the hydration system is supposed to weight 100 grams, but really weighs 115, it is worth noting. We must physically check these things, because they don’t always match up with what the product brochure says.

5) Install the product and any accessories (valve extenders, rim tape, tires, tubes, laces, bar tape, cables, kitchen sink). If everything goes smoothly, we’re good to go. If something goes wrong, we think to ourselves, “Well, this is going to take longer than expected…” Products break, don’t fit, and sometimes have poor instructions that leave you doing the job twice. This often results in frustration, but we learn something valuable and can pass it along to our faithful readers.

6) Use the product. Tweak it. Photograph it some more. Change the tire pressure. Change the brake pads. Put the product on a different bike. Use it in a different weather condition. Push all of the different buttons. Try all of the different functions. Record, measure, sprint, stop, and dance a jig. The idea is to put the product through ‘accelerated testing’ – use the product in many more ways than the average consumer would in a given period of time. Poor weather is a bonus. This testing normally takes place during our personal training time, which means that our training is at the mercy of the product. If something goes wrong, we must bring out the camera phone and take notes on what happened.

7) Write the review. Write HTML code for links, make your words pretty, and to add emphasis where desired.

Let’s go through a few examples (the actual reviews are linked at the bottom of this page):

1. Profile Aero HC System Review – This is a product that I was eager to try, but the review took on a life of its own. Profile contacted us about their new product before it was available to all of you. Often times a company will have an embargo date on this type of release. That means “We’ll tell you about the product now, but you can’t make anything public until X date.” It’s a gentleman’s agreement; if you publish early, the manufacturer can and will cut you off from future access.

I received the product, along with a grab bag of aerobar product that I had inquired about, with the intent of publishing a separate article with fit notes. As it turned out, the Aero HC System did not physically fit on the aerobars they had sent when my fit was dialed in as-necessary. This was totally unexpected and meant that I didn’t get to actually ride with the hydration system. The two topics (Aero HC System and bike fit notes) ended up being so closely tied together that it became a single article. Profile also sent their HC Mount after-the-fact, which does work with the T3+ Carbon bars in my fit configuration, and we ended up including this in the review as well.

2. Hed Jet 6 650c wheels – this was done as two articles. First, a product announcement and photo gallery, as the product was brand new and had yet to be written about by a triathlon publication. Second, I rode the wheels on my 650c bike for about three weeks during my usual training schedule. The full review was published about four months after the intro piece. There were no hiccups or problems, which made for a quick evaluation. The only reason that the test riding got delayed by several months was that I already had too many other wheels in queue; I operate on a first come, first serve basis.

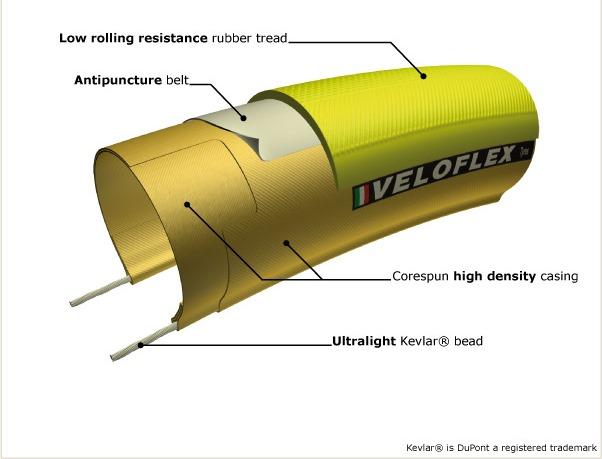

3. Fast Tires 2013. This was an article series that wasn’t so much a review as a large overview of many brands and products. Information in the article came from manufacturers, third party sources, and my own personal experience (much of which is based on product that I purchased and used well before my time at Slowtwitch). I did not do any specific test riding or photography at the time I wrote the articles, but rather relied on past photos and new information from manufacturers. This type of article takes time simply because of research, checking weights, prices, finding useful data, etc.

That’s just a few examples. At any given time, I have about 30 stories in queue, waiting to be researched, ridden, and written. That also means that there is not a direct correlation between the ride time and the publishing date. I may publish two 700c wheel reviews two weeks in a row, but both wheel sets were ridden for two independent periods of several weeks over the past few months. It just so happened that all of the information (pricing, availability, embargo dates) came together and resulted in a close publishing interval.

Generally, we use the product a minimum of a few times if it is simple, or up to a year if it is complicated or requires a long evaluation (i.e. saddles). On occasion, we'll farm out some long-term testing to friends, along with some testing requirements – 'Ride these tires for X miles at Y pressure, and note the frequency, size, and circumstances of any punctures that happen.' We're known for in-depth content, so we typically choose higher quality over faster publishing speed.

Press Events

We’ve had a handful of questions surrounding press events and how they work. A press event is anything that involves journalists being invited to a specific location to learn about a single manufacturer’s products. Sometimes only three or four publications get invited, but sometimes it’s as many as ten or fifteen. These big events are usually timed with a very important product introduction for that manufacturer; they want a captive audience to learn all about it. Here are a few examples of press events I’ve attended this year:

-Stages Power press launch, Boulder CO, January 2013

-Osmo Nutrition test, Boulder CO, January 2013

-SRAM, Zipp, Quarq 2013 product release (Vuka Stealth, Vuka Fit, 404 Firecrest 650c, Riken, Elsa), Tucson AZ, February 2013

-Shimano 9000 Mechanical and 9070 Di2, new 2013 carbon wheel official press launch, San Diego CA, March 2013

Who pays for the trip? In almost every case, the manufacturer that hosts the event pays for each editor’s flight, meals, airport transportation, and hotel room (the editors and/or publications are NOT directly compensated by the manufacturers in any way). I’ve heard some people say that this slants the resulting content, and that the publications should pay their own way. It’s as simple as this: If manufacturers didn’t pay, nobody would show up. There are so many of these events that we’re often left turning them down due to schedule conflicts, so the ‘pay-your-own-way’ events would be empty. Also, as a matter of practicality, most triathlon and cycling publications just don’t make enough money to pay for this type of expense. Personally, I enjoy going to some of these events, but they are definitely not a free vacation. These events always make an editor’s week much more hectic, as they often stay up late at night in their hotel room to maintain their normal publishing schedule in addition to what they’re doing at the press event. It’s not unlike business travel in almost any other industry.

Article Comments

Most of you are aware that you can comment on our articles using a Facebook account. It is worth noting that the article author does not have any way of being notified when these comments are posted. It simply does not exist. If someone posts a comment in response to a comment we’ve already posted, we can be notified from our own Facebook account – but standalone comments on the page do not work that way (they are in no way attached to our name). I mention this because we often get article comments and direct questions several months or years after the article was originally published. The only way we know about the comment is by physically checking each article. If I publish three articles per week for fifty weeks a year, that’s 150 articles each year. There’s no way I can check them all. Questions about old articles and topics are best housed in our reader forum, where our 60,000+ registered users can assist you.

Do you really test that much stuff?

I’ve been asked if we really do test this much equipment. You must only be riding each tire or wheel once through the parking lot! There’s no way you can test that much stuff and do an honest evaluation!

It’s a lot of product, but we really do test it. I can’t speak for the entire Slowtwitch staff, but I get accused of having a revolving door for equipment by my friends. In fact, it’s very rare that I do more than one or two bike rides without changing something about my setup. Be it a wheel, tire, cleat, pedal, helmet, bottle cage, light, saddle, or something else. I also currently have three tri bikes to make this possible. At any given time, I need to have at least one of them operational for actual riding. Once a test is done, the bike gets torn down and rebuilt with whatever is next.

All images © Greg Kopecky / slowtwitch.com

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network