Anatomy of Olympic gold – Part 1

After the judges studied the finish line photo, Switzerland’s Nicola Spirig eked out the win in the women’s 2012 Olympic Triathlon over Sweden’s Lisa Norden by 2 inches. While awaiting the decision, NBC commentators studied replays from four different angles and admitted they could not tell who had won and surmised that the gold medal might be shared.

By such a tiny margin comes a wide gulf in the impact between Olympic gold and silver. Rightly it leaves both competitors bathed in mutual glory for the heart they brought to the contest and the adrenaline they brought to the finish. And such a statistically minute sliver of a margin begs questions whether one or the other truly deserves all the glory and distinction. And while those electric final yards will be what almost everyone will remember, it is but the tiny tip of an iceberg of sweat, tears, nerves, hard work, belief, luck, strategy, planning and psychology – that went into it.

Both women and their coaches brought greatness to their clash. Lisa Norden of Sweden was the 2007 Under 23 ITU World Champion, the 2009 ITU World Championship Series runner-up and 2009 Grand Final runner-up, the 2010 ITU Sprint World Champion and the 2011 $151,000 winner of the Hy-Vee Triathlon. Norden’s coach Darren Smith brought an astonishing 4 current women to the 2012 Olympic start line – and one of his recently departed athletes also made the cut. By race time, Smith and Norden were a smart, formidable team that pushed the Australian coach and his Swiss charge to the brink.

Spirig’s record was only slightly less glittering than Norden’s. The Swiss came to 2012 a two-time Olympian who had won the ITU Junior Worlds in 2001, the ITU Under 23 Worlds in 2005, 3 European championships, 2 World Cups, 2 World Championship Series races and the final 2 Olympic distance World Triathlon Series events before the London Olympics. Her coach Brett Sutton’s record is monumental. He coached five ITU Olympic distance World Champions and co-coached another. He coached one man to Olympic bronze and a woman to silver. He has coached 4 ITU long distance World Championship gold medalists, an Ironman 70.3 World Champion and, to top it off, he coached Chrissie Wellington to her first two Ironman World titles in 2007 and 2008.

While Sutton’s résumé might tempt people to think that he pumps out gold medalists like a machine, this road to Olympic gold was anything but a foregone conclusion. During their 6 year odyssey together, Sutton and Spirig weathered and made innovative adaptations to her training through three periods of injury and a debilitating asthma onslaught, overcame huge personality differences and communication barriers, honed and strengthened Spirig’s body, rewired her psychology and confidence, and fortified her competitive edge with a master’s understanding of her high-octane opponents and the tactics required to prevail on the day that mattered most.

This is their story.

The Four Year Plan

Nicola Spirig started her triathlon career in 1998 coached by her father Sepp and she did very well under his guidance. She won junior European and World Championship titles, made the podium at Under 23 Worlds and made top 20 at the Athens Olympics. “My father did indeed a very good job,” she said. “I wouldn't still be in triathlon without him. He understood to lead me slowly into decent training, without putting pressure on me or pushing me.” After the Athens Olympics, she says, “I knew I wanted to find out where my limits are over the coming years. My father wasn't someone who could push me to the limits, and I didn't want him to, either, as we had and still have a great father-daughter relationship and I didn't want to endanger that.”

Sensing that she wanted to be pushed to a new level that she did not want her father to supervise, the emerging Swiss champion had been aware of a coach whose summer squads were based in Leysin. This coach was controversial to the outside world and failed to succeed with many athletes. But he also engendered loyalty and gratitude with dozens of triathletes he guided to greatness. “I guess Brett and I were watching each other for several years, and first I didn't want to work with him,” she recalls. “I switched to Brett as a coach in 2006 after a lot of doubting.”

At first they were like oil and water. “I don't think I am a typical athlete with Brett,” recalled Spirig. “He needed a lot of nerves, especially in the first few years. We were always arguing.”

Sutton sums up their early process with a brilliant summary: "Nic said that's impossible to me a lot," said Sutton, "but went and tried anyway. And so impossible became improbable, then possible, then probable, then doable, then done."

Two years after Spirig switched to Sutton, she was thrilled to finish 6th at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. While she had success before she joined with the legendary coach, she had been beset with leg injuries that limited her great potential. “We looked at her stress fractures and devised a different program – run one day and take one or two days off,” recalled Sutton. “It worked remarkably well. She thought it was the greatest race she ever had.”

While Spirig basked in the moment, Sutton had his eyes on the Olympics four years ahead — and how to conquer what lay in her way. “It’s pretty much like my days as a horse trainer,” said Sutton, who also trained racing greyhounds and spent some years as a boxer when he was young. “You have to know the form of everyone around you. After the Beijing Olympics, I spent three and a half years trying prepare Nicola to beat [2008 Olympic champion] Emma Snowsill,” who won with a dominating run that was nearly two minutes better than the rest of the world.

In Sutton’s mind, the key objective was “to prepare Nicola for the last 300 meters of the Olympic run. At that time, Nicola had to be making her move early on. Unless she got a little gap on the bike, I did not see taking her 2009 level run and holding on to the lead from Emma for the full 10k.”

The day after Beijing, says Sutton, he hatched a plan to train Spirig to negate Snowsill's run – and the ace up his sleeve was that he had trained Snowsill for her first World championship in 2003. “I knew Emma’s abilities and non abilities,” he said. “The last 200 meters she does not have a kick. In that she is identical with 2008 ITU World Champion Helen Jenkins, who also does not have kick in my opinion.”

So what did they do with this insight? “Our goal was to get the first 3k of Nicola’s run [faster] to cope with the harsh realities of speed,” said Sutton. “She needed to take it out hard and then develop the strength and endurance to make sure she would have legs for the last 300 meters.”

A controversial coach

To detractors and critics, Sutton is seen as a harsh drill sergeant who takes a high number of talented athletes, overworks, over trains and over races them, and then discards the broken and the weak. The critics say he then takes the survivors and reaps the glory of those with freakishly good biomechanics, unbreakable muscles and indestructible tendons. Another criticism is that he operates like a Marine sergeant who breaks down the high spirited until they obey without question. Legions of his athletes adamantly dispute those assertions and assert that he is among the best in the sport at avoiding and treating overtraining and overuse injuries and actually protecting Type A athletes from their congenital inclinations to overwork. Far from applying a one-size fits all methods, most of his athletes say he takes an individual approach and applies very different regimens to athletes of different psychological make ups and unique physiologies.

Undoubtedly, Sutton remains the most controversial coach in the sport not only for his unorthodox ideas and methods, but also for the shadow that hangs over his life for a 1988 incident to which 11 years later he pled guilty and received a suspended sentence for having sexual relations with a minor he was coaching in an Olympic-level swimming program. Since then, there have been no other such charges. While he was banned from coaching in official Australian programs, Sutton has achieved a measure of redemption as he has guided dozens of men and women to the heights of their sport and enjoys a lasting loyalty from some of the most intelligent women ever to compete in triathlon. They include Emma Snowsill, Loretta Harrop, Chrissie Wellington, Siri Lindley and, assuredly, Nicola Spirig.

The first step – away from the arena

While pursuing triathlon success, Spirig had finished the first year of a law degree in a Zurich university but kept taking time off for the 2004 and 2008 Olympics. Sutton saw this protracted delay as a crucial road block to Spirig’s dream and his plan. “I thought that always nagged at her insecurity about not finishing what she started,” said Sutton. “To be a professional sportsman in Australia they will be proud of you. But in Switzerland the only sport that counts is skiing. Other than that – and Roger Federer in tennis — nobody cares about any other sport. If you say you are a professional athlete, you are treated like an ex convict. They believe you are trying to get away from working. Nicola absorbed this disapproval from a family point of view and the Swiss culture point of view. It would be a very, very black mark on her to think she chose sport over school.”

Sutton encouraged her to return to university and get her degree. “I was hoping that would be the first step in making her ready for 2012,” he said. “In her opinion and mine, we agreed — let’s get the University out of the way. Maybe another person would take 2 or 3 years. But Nicola’s intelligence is quite frightening when she puts her mind to it — and she was done by late 2009.”

While she maintained training fitness and did some racing in midsummer of 2009, taking 2nd at Kitzbuhel and winning London, she did not return to full time racing until May of 2010. Whereupon she had an excellent 2010 in the elite ITU World Championship Series, taking 4th at Seoul, 1st at Madrid, 2nd at London. At the Grand Final at Budapest, Spirig took what for most competitors would have been a satisfying bronze medal. But for Sutton, what happened there was a red flag that prompted a radical change of plan.

At Budapest, Snowsill ran 33:08 to win by 1:42 over runner-up Emma Moffatt and 1:45 over Spirig. Moffatt and Spirig had the next fastest run splits and both ran 35:05.

“Emma Snowsill destroyed everyone at the Grand Final at Budapest,” said Sutton. “We had another meeting and thought to ourselves, ‘As things stood, no way we can cope with that kind of performance.’ What we thought we needed to do wasn’t gonna be good enough. To go to the next level, we should at least test Olympic preparation. Most people come to the Olympic year and try to raise their game but they have no time to adjust if things go badly. I thought we will do a dress rehearsal for Olympic training at the end of 2010 and into 2011. Nicola had no stress fractures in 4 years, so maybe her legs were OK with an increased load.”

A setback

They decided to do the actual training that worked with Snowsill – intense runs, more run mileage and more times running per week. They also cut back on her swim and bike training. Spirig, as Snowsill had done with Sutton, ran nearly every day, sometimes twice a day. “I believed if Nicola could cope with that, that she could out sprint Emma,” said Sutton. While the increased run training may well have been the underlying reason, Spirig incurred a stress fracture that led to a periosteum strain while training at a [non-Sutton] camp in southern Switzerland in late Fall of 2010.

Spirig stopped running for a while, then showed up at a Sutton camp in Gran Canaria Island off the coast of Spain in January, but it got worse. At the end of February when she the arrived at Sutton’s camp in Thailand, she did two runs and the leg was out of commission indefinitely. “By February of 2011 we were broken,” said Sutton. “I got very harsh stares. But we found out something valuable — that Nicola’s body said very clearly she cannot take that type of training.”

While his athlete was unable to run or bike while the periosteum healed, Sutton put Spirig on some extreme alternative training at a camp in Australia’s Gold Coast. As he had done with Loretta Harrop when she was injured in the months leading up to the 2000 Olympics, he had Spirig swimming 60 kilometers a week in 8k sessions and water running every day in a deep water pool which kept her in high aerobic tune. He also had her working out in the gym.

“When we got her in the gym, I thought she was joking,” said Sutton. “She was terrible. She could do pushups and one legged squats. But when she tried to lift the weights, I thought she was kidding. ‘OK, that was fun. But now let’s get serious.’ I came to realize that she has a large frame and looks really strong but she was not strong in that way. To be honest, Nicola is not a gym girl. As you can see, when she walks around she looks very strong – she has a perfect body for the sport. Still she is very self conscious about her big shoulders, arms and strong legs. Society drills the image of Barbies into the heads of girls.”

At that time, Sutton says he had Spirig working with weights with former Australian swimming colleague Dennis Cottrill’s swimmers “so she could feel she was still training when she was injured,” said Sutton. “But we only did it to keep her mind from going nuts. We built real strength with sports specific exercises in the pool and on the stationary bike. Once she was back running we stopped all the weight work.”

Forging a tougher psyche

During Spirig’s emotionally trying setback, Sutton did his most serious work on her mindset. He drew upon the example one of his triathletes, 1999 ITU World Champion and 2004 Olympic silver medalist Loretta Harrop of Australia. “I told Nicola she did not have Loretta Harrop’s head,” he recalled. “Loretta was hard as nails. Loretta could handle situations – like how she handled things after her brother Luke died [during a 2002 training ride, struck by hit by a hit and run driver]. She controlled the controllables around her better than any athlete I’ve ever seen. And when adversity knocked her down, Loretta roared back. She just had a different mindset.”

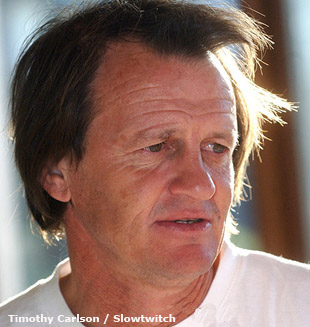

Sutton explained to Nicola: “Yes, you are physically very tough, but mentally you are not tough.” When Spirig retorted, “But I'm not Loretta!” Sutton did not back off. “That's the point,” he said. “The old Nicola Spirig will not win a medal. She has to change and be more embracing of the way Loretta (pictured left here with Sutton) did things.” “But I'm my own personality!” “Your personality is not gonna cut it. If you want a medal at Worlds or the Olympics, you can’t care what you were. That's your weakness.’”

Eventually that message started to get through. “I told her, ‘When you are injured, you have to adapt and improvise – and you have to stay tough,’” said Sutton. “I rammed down her throat ad nauseum, ‘Do not get soft!’ She responded well and that gave me great confidence.”

That is Sutton’s universal message. In a letter he sent out to all of his athletes looking forward to the 2012 Olympics, he wrote: “’If you want a medal, you have to change your personality. To be really good, you do not just want to be in the Olympics. You have to intend to win.’ I told them that each of you have to change your mentality if you want to go to the next step and be really competitive in the biggest race in the world.’ Nicola bought into that. Instead of falling to pieces, I started to see that girl was a rock.”

Meanwhile., it was taking some time for old horse trainer to find a way to communicate with the intelligent, reserved Swiss woman.

“I spent 2 or 3 years trying to find a way,” said Sutton. “She’d go awful in training and at first I would try to psych her up. But it never worked for her. She was so different. In person, she would never talk of triathlon. At the end of a workout she would say, ‘Thank you,’ and walk off. The other guys in the squad thought it was funny. You see, if I talked to Nicola like I talk to Xena [Ironman triathlete Caroline Steffen], she would not do anything. On the other hand, we found a way. Nicola and I communicate all the time via email and texts and I came to understand this was the way. It is not like communicating face to face. In person, Nicola never tells you the whole truth. But in emails or texts, she was happy to give it to the coach both barrels. One time we had 600 texts in a month.”

Spirig healed enough to run and bike again, and by mid-season 2011 she was far from peak fitness but good enough to finish 8th at the London World Championship Series Olympic preview event and nail down her Swiss Olympic berth. “She was not ready for the Olympics at all, but at that stage I thought it was fantastic,” said Sutton. “All she needed was work.”

After the high mileage, high frequency running experiment failed, Sutton put Spirig back on her 2008 regimen. “We went back to run one day and run hard. And then we do not run the next day or two in a row. Particularly, she never ran two days in a row on the ground. She would alternate one day on the ground and one on the treadmill.”

The treadmill, says Sutton, has been a key element of his elite training for years. “There is less impact and less resulting stress on the legs, the less she hits the ground. I used the treadmill with [ITU World champions] Loretta and Emma Snowsill and Siri Lindley.”

During training and racing after the London WCS event, Spirig suffered a series of sub-par performances – 6th at Hy-Vee in Des Moines that Norden won, 20th at the Beijing Grand Final, and 25th at the Yokohama World Triathlon Series.

“Through all this she got worse and worse,” recalled Sutton. “During that period, I discovered she was hindered by the lung problem – asthma. Looking back, the lung problem actually started three weeks before London and got progressively worse with all the long traveling. I had her take a month easy and at that point we just stopped doing any hard training.”

By December 2011, Spirig was rested and fully healthy when she went to a Sutton camp in the Grand Canaria Islands where the signs were good.. “As soon as her lung was fit, she was on fire, faster than ever in her life,” said Sutton. “The Canaria camp put her in the sun, she was bang on in training. She was so much quicker than before and I felt she had gone on to the next level. But I was scared she was pushing too hard.”

Early 2012 – The setup

Spirig remained strong and pulling at the reins at the season opener at the Mooloolaba World Cup where she pushed hard to stay with Erin Densham into the run. “Nicola was hanging on and I said ‘Back it off,’” said Sutton. “I told her to sit back and at a quarter mile try to outsprint them all. And it went terrifically well.” Spirig was 2nd to Densham and Lisa Norden got 10th. At the Sydney World Triathlon Series event, Densham stayed hot and won, with Jenkins 2nd, Andrea Hewitt 3rd, Gwen Jorgensen 4th and Spirig 5th. Convinced that extensive travel triggered her asthma, Sutton kept Spirig out of San Diego and sent her to Eilat for the European championship instead, which she won.

Final races before London

In this period, Sutton had Spirig adding strength work on the bike and a lot of hill running. With the London Olympics in mind, he had her do run workouts in the morning — 2 sets of 5-times 80 meters up hills – and swim at noon. “She loved it and got used to it,” said Sutton.

Sutton saw Madrid as a key preparation for the Olympics. “I always knew that the Madrid bike and its hills kills speedy runners,” he said. “No matter how slow you go, the Madrid bike course takes it out of the legs.’” Sutton also saw Madrid as the end of Spirig’s strength work audition. “Nicola knew the bike ride was very hard in Madrid but I did not put pressure on her,” he said. “I told her, ‘If you get beat, don’t worry about it.’ I wasn’t interested in a podium at Madrid. I was interested in the Olympics. I told Nicola this was a BS race.”

The day before Madrid, he had her swim and bike the entire course. After those workouts, Spirig felt exhausted and told Sutton, “I’m tired, I’m dead. You killed me.”

But on race day, as each kilometer passed, she settled in. “Once I saw her smile and nodding to me all was OK,” Sutton said, “I knew she was totally in control. I told her, ‘Hold it up and then give it to ‘em,’ meaning wait and sprint at the end. She nodded and smiled and outsprinted Aileen Morrison by three seconds for the win. When Nicola breaks into a half smile – look out!”

A month later, Spirig went to Kitzbuhel and had a preview of her Olympic duel with Norden — no holds barred. They mirrored one another on the swim and the run. Then they uncorked the two best runs. Norden outran Spirig 34:55 to 34:57, but Norden’s tarrying T2 was 5 seconds slower and left Spirig in front at the finish by 3 seconds.

In the days before her final World Triathlon Series race at Kitzbuhel, Spirig had told Sutton that she wanted to podium. “She never thinks like that,” said Sutton. “At the same time, her training went berserk. She went harder, harder, harder every day. I thought things were getting worse and worse. ‘My God she hammers every session and cannot keep it up!’“

Sutton admitted that he could couldn’t fully control Spirig’s fiery workouts, so he improvised an outside-the-box solution. “I tried to slow her down, throw water on her but it didn’t work,” he said. “So I sent her to the Antwerp 70.3. Straight away people said, ‘You’re insane!’ It was a 10 hour transit by car and a 4 hour race and I knew that would keep her from going crazy.”

Sutton took some heat for his choice. “People thought ‘My God, the Olympics are two weeks!’ But the way she was training was ridiculous. And sending her to a short sprint race in Hamburg was also ridiculous. It would be an insane run — Erin Densham shows up and she is running a 15:50 5k. If Nicola went there she would leave full of lactic acid. So instead I sent her off to run 21k where it would be aerobic all the way. It was a long race and would settle her down and she would have 4 days not going crazy training. And then she would have 2-3 days to rest and that would get her ready her for the Olympics.” Spirig won Antwerp by a country mile, and calmed down as Sutton thought she would.

Part 2 – The Olympic race will appear Friday