Cory Foulk hears a different drummer

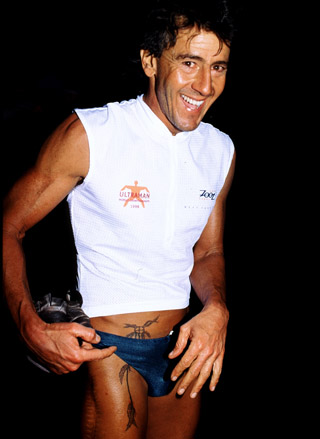

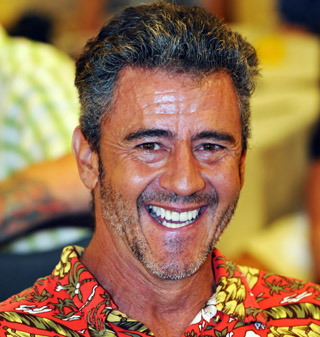

Cory Foulk is 52 years old and has finished 47 Ironman races and 21 Ultraman events. He is an architect and an environmental scientist, a gifted but not a great athlete, has a wicked sense of humor — and at the same time has a firm grip on the spirit of the sport. He is a good person to talk to if you get too caught up in the obsession with the high-tech wonders that are a part of the sport of triathlon – and can provide equally valuable perspective if you have a grouchy, old-school fixation that won't allow you to enjoy or even see the value in that same beautiful modern machinery. Foulk has been involved in the sport of triathlon from its first decade and is still going strong. Fifteen years ago, he did Ironman Hawaii riding barefoot on a rusty, neon green, 61-pound Schwinn Typhoon beach cruiser he bought for $15. When he rode it, he wore foam flames Velcro'd to his helmet. And he has done the same event on a modern bike loaded with eclectic, high-end components he has accumulated over the years which, he says, cost him a total of $12,000. And he has found joy and meaning in both experiences.

"Absolutely the greatest thing about doing an event like Ironman on a stone age piece of equipment is that there is absolutely no pressure," says Foulk, who did that feat in 1996 – the year that Luc Van Lierde set the still standing Kona course record of 8:04:08. Foulk's feat took him 15 hours 46 minutes and 57 seconds.

"On a bike like that you can sit back and enjoy the race – because that is your only option," he says. "You can take your Type A personality and throw it out the window. While a PR is out of the question, there is always a challenge on a bike like that just to finish within the cutoff time. And I found on those days, on a bike like that, there is always a point where I realized that maybe I had bitten off more than I could chew. I had to face the reality that maybe I would not make it. And that is a cool feeling! That was what attracted me to the sport. That is what I came to triathlon for. Back in the old days, the finish was not guaranteed."

Both his current (not the 1996 model) $280 beach cruiser and his very modern, cutting edge bike sit comfortably together in his Kailua-Kona condo. "My $12,000 bike is a great bike," he says with enthusiasm. "It is almost impossible to even describe the pleasure to even have a piece of equipment like that. For me honestly, I think it is even cooler that I can ride both ends of the spectrum. After I ride the big old bike, I really notice the difference."

Foulk's appreciation for modern technology – a signature trait of triathletes if there ever was one — runs deep. He had BHR hip resurfacing surgery in December 2005, which rescued him from enforced premature triathlon retirement and enabled him to do 11 Ironman events, 7 Ultraman races and at least two ultramarathons since then. With typical confidence, he never felt the urge to baby his new cobalt and chromium alloy hip joint – and he runs faster than he has for a quarter century. In fact, after a spate of speed training in 2009, he found himself running 5ks in under 16 minutes, a speed he had not achieved since his 20s. And in 2007, at the age of 48, he finished third overall at Ultraman Canada, saving his spot on the podium by a margin of 4 seconds.

He says his goal now is to stay healthy and to become be the first to finish in 15 different age groups at Ironman Hawaii. Although he has a modest, self-effacing humor, fulfilling that goal would require him to be racing until the age of 95. While most would scorn him and think it was a preposterous joke, Cory Foulk would laugh and say, "Why not?" After all, he has a track record of audacity.

THE BEGINNING

Cory Foulk was born in 1958 and grew up in Boulder, Colorado, the son of water and power employee William Foulk. He satisfied am unquenchable appetite for physical challenges, adventure and choosing the less traveled, non-conforming path from the beginning. As a lad, he and his friends would flood the street near his home in winter to play hockey on bicycles. "We didn't use sticks — instead we used our wheels to slap the puck," he explains. "It required astonishing balance and the most intense aerobic activity you could imagine. It had a very high ratio of down to up time and a huge amount of sliding in between." He also loved riding his Suzuki TN 400 ("the most dangerous dirt bike ever built," according to one dirt bike magazine) on trails east of town – then started running to get in shape for motocross. Throw in swimming at Boulder High, soccer and an aptitude for science and, briefly, you had an Air Force Academy cadet. "I didn't take to authority the way the rest of the guys did," he says. "I was one year younger than the rest and got hazed a lot – and I fought back by putting shaving cream in album covers, sticking it under their doors, and stomping on it. I really could have used some Super Glue back then. Finally, the Air Force Academy and I called it a wash and I enrolled at CU Boulder."

At CU, Foulk started racing bicycles, did a lot of snow skiing, and ran the Mile High Marathon in Denver on a whim and ran with the leaders for four miles, finished in great pain, crawled into bed for a few days and subsisted by drinking water from his bathroom faucet. During that recuperation, he decided "this sport was meant for me. But I realized I'd probably have to put in a few miles of training."

During this time, Foulk dated twins – simultaneously. "In the ‘70s Kelly and Tracy Van Deusen were really cute and I would ride them out to the Boulder Reservoir Res on a 10-speed. One would sit on the handlebars, the other on the seat and I'd stand up and pedal the whole way. I'd drop them off at the beach, work my lifeguard stint, and ride them back at the end of the day." Foulk insists that jealousy was never a factor. "We never did anything too serious." Kissing? "Yes. It didn't bother them — and I was certainly fine with it. It was hard work — but the kind of work that was good if you can get it."

THE GRADUATE

Foulk graduated from CU with a double major in molecular biology and aerospace engineering, and moved to San Diego in the summer of 1979. Rather than look for work in his academic field right away, he earned some money teaching sailing at a Hobie Cat rental place not far from the Mission Bay Aquatic Center where Scott Tinley used to work and a few blocks from 1979 Ironman winner Tom Warren’s Tug’s Tavern. Already swimming and running, Foulk took up cycling when a friend talked him into entering the Tecate-Ensenada bike race on a borrowed bike. "I remember coming down a huge descent with billions of other riders," said Foulk. "I was using rat trap pedals and there was a sign which said "river crossing" in Spanish. When I came around the turn, the road was under water and bikes were piled up in the current and guys were going down. It was a hopeless fiasco – and I loved it."

Surrounded by triathlon history and an enthusiastic partaker in all three disciplines, he did not yet take part in any official triathlon.

At the end of the summer, Foulk was running daily with a 37-year-old neighbor and became concerned about the man's spirited teenage daughter who got into trouble that involved drinking and driving a car without permission, which led to her failing to graduate with her high school class. When the neighbor sent his daughter to a convent in Kailua-Kona to set her straight, she started writing letters to Foulk detailing "how much it sucked to be in the convent and how cool Kona was," he recalls. "That was the end of summer of 1979. So I started to craft a plan to rescue this girl from the convent."

Foulk arrived in Kona with $85 in his pocket and a surfboard and found free lodging in a tree house on the beach next to a recently burned out home. While he did not have to tunnel his friend out nor rappel her away of the nunnery, he did sweet talk the chief nun into letting the girl work in a restaurant outside the convent and eventually settle into her own place. While the girl went on to Australia and then returned home to attend UC San Diego, Foulk had found his home in sleepy, small town Kona which had at the time, he recalls, a population of 580.

Thousands of miles from jobs that might suit his academic credentials, Foulk worked as a tour guide and diver on a glass bottom diving boat, then transitioned into a co-owner of a small firm that caught tropical fish and sold them to distributors. During this time, he dusted off his talents as a freelance illustrator and rendered drawings of buildings designed by local architects. Because of his background in engineering and his talents as an illustrator, his clients urged him to take the rigorous architects’ exam. To his befuddlement, he was one of only 2 percent who passed the rigorous, 5-day exam the first time he took it. So Foulk had the rare distinction of obtaining his architect's license without an academic degree in the field.

He was also heavily into the local swimming and running communities. And at the end of 1980 he and his friends enthusiastically accepted an invitation to work an aid station for the Ironman that was coming to the Big Island in February.

INTIMATIONS OF THE IRONMAN SPIRIT

"It was 2am and you could hear a song by The Knack coming out of the darkness," he remembers. "Sure enough, this guy rides in from Hawi on a bicycle with a boom box in the front basket carrying a five pack of beer and a pack of Marlboros. It wasn't Walt Stack [the legendary San Francisco Dolphin Club member who took 26 hours to finish that year]. It was some younger guy who got off, had a smoke, chatted us up, drank a beer and rode off. I love that stuff. It was a small piece of the craziness I loved about the Tecate bike race. I don’t know if this guy even finished the run or if it mattered to him. I think back in those times. It was just about participating. It wasn't 'God I've got to finish hell or high water because I told everyone I would!' It was just a couple of wing nuts who showed up on a Saturday to do something they had never done before. I really liked the whole group it attracted."

It was February of 1981 and Foulk had yet to do a race where the swim-bike-run was combined.

FIRST TRIATHLON

Foulk did his first organized triathlon at the Keauhou half Ironman in the summer of 1983. "I had a great time," he said. "It was the funnest damn race. They offered a sprint, an Olympic and half Ironman distances all in one. Relays and high school teams were welcome. And they had a mass start. It was unbelievable what a circus it was. They didn't have a canine division, but they had one guy with a dog who rode on a carpet set on the top tube. I don't know just how it was set up. I was in front and did not get to analyze it too much. HE PAUSES That is usually a good indicator how you are doing. If you are standing in the environs of the canine division, it's not going too well."

THE MERRY, GOLDEN '80S

Foulk will always look back to the 1980s triathlon scene as a golden time. "Back then there wasn't a single triathlon that wasn’t just incredibly fun," he said. "That's because every single race brought a whole new set of ideas on the part of every athlete about how to tackle this sport. People cobbled their equipment together in unique ways — different size wheels front to back, all kinds of nutritional supplements. Some ideas were completely off the wall — somebody thought pre-race food was hard on the system and caused race day cramps at Ironman. So they tried no solid food for three days before the Ironman."

How did that work out?

"A lot of guys were face down in the lava fields out by OTEC road, now known as the Natural Energy Lab," he said.

Some outlandish tech ideas? "I remember Mark Allen showed up to Kona in 1987 with a cable hooked atop the bike stem and attached to a belt around his waist. It was supposed to give you extra power on the bike. It gave him a lot of power — and a kidney malfunction and he ended up in the hospital." [Allen says there was no connection between the cable and his post-race distress. The Grip says he tried the cable, which had been used by Dutch time trial riders, but threw it off halfway through the race because it didn't seem to be working.]

Foulk remembers one guy devised a tech trick to psych out his rivals. "In the early ‘80s, a guy named Dave from Santa Barbara put two magnets on his wheels instead of one so when people looked at his bike computer they would think he rode twice as far and twice as fast as he did in training."

Cory Foulk saw all the hits and the misses as part of the journey. "We were just trying stuff out, throwing spaghetti on the wall to see what stuck," he said.

PART ONE OF TWO — THE CORY FOULK TALES