Gino Bartali and The Road To Valor

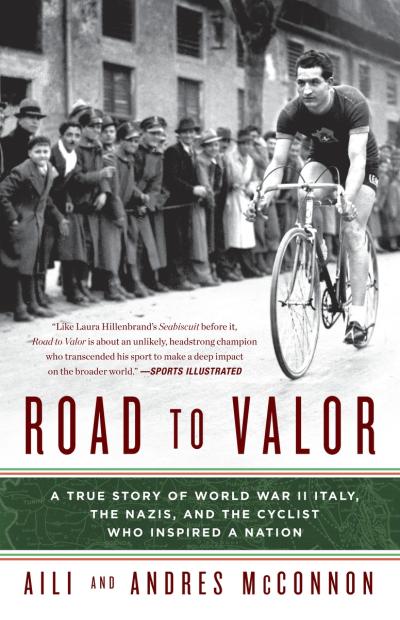

Gino Bartali, two-time winner of the Tour de France, helped save the lives of Jewish refugees during WWII by ferrying documents hidden in his bicycle and by sheltering a Jewish family in an apartment he owned. This past May, the new Israeli professional cycling team, commemorated Bartali during the 100th anniversary of the Giro d'Italia with a special ride tracing his war-time document smuggling routes.

"My father used to say "Good is something you do, not something you talk about," said Luigi Bartali, quoting his father, Italian cycling great Gino Bartali.

It was May 15th, 2017, and Luigi was speaking in the Palazzo Vecchio, the grand town hall of Florence overlooking the piazza with Michelangelo's famous statue of David. Luigi was speaking to a group of Italians, Israeli's new professional cycling team, and several members of the media. I was there because I had written a book chronicling Bartali's life as a sportsman and secret World II hero.

Luigi was speaking to us that night in advance of a special bike ride planned for the next day that would trace the route Bartali took between Florence and Assisi during World War II ferrying documents to Jews hiding from the Nazis and Fascists.

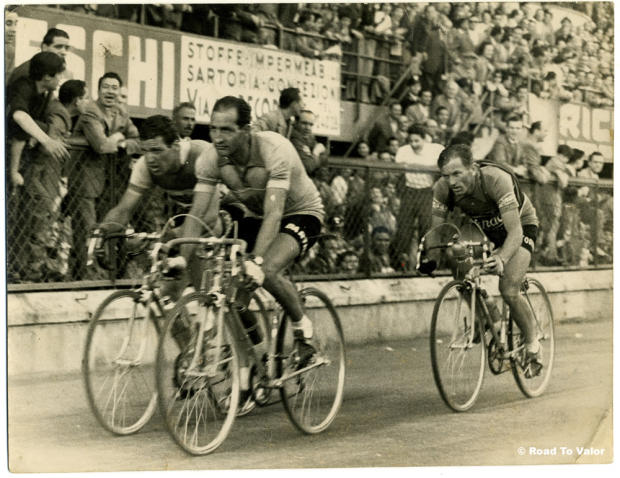

Florence and all of Italy were abuzz in May as the country celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Giro d'Italia. Towns and cities were enveloped in pink – the color of the winner's jersey. People waved pink flags and hundreds of pink umbrellas were strung like chains of lanterns between trees. Vintage bicycles- painted rose, fuchsia, salmon and so many more shades of pink – were found everywhere. Several stages celebrated cycling legends like Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi and others.

Bright and early on the morning of May 16th, the day before the Giro stage that officially honored Bartali, our group suited up and bumped over the cobblestones of Florence on our bikes. First we made our way to the little town of Ponte a Ema, about four miles southeast of Florence, where Bartali was born. The tiny, dusty town has one café and is surrounded by picturesque rolling hills, vineyards, and the pointy green cypress trees that define Tuscany. This was the early training landscape for young Gino.

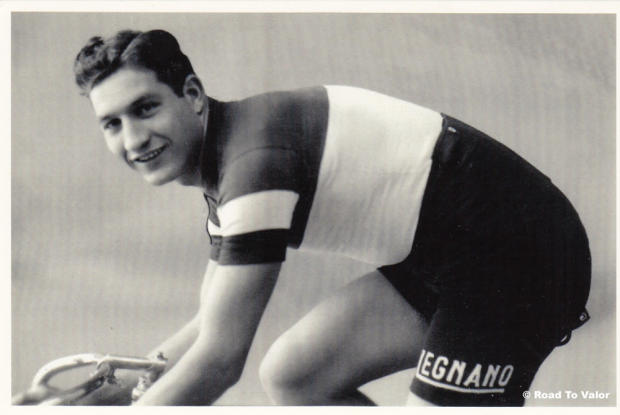

Gino was born here in 1914 into a humble family. His father was a day laborer and his mother worked in the fields. He gained fame when he won his first Giro in 1936 and then the Tour de France in 1938. Then World War II hijacked Gino's career. Gino, like so many other young Italian men, was drafted into the army. Bartali began as military messenger and received special permission to travel between towns and cities on his bike to continue training.

By the fall of 1943, the Nazis arrived in Italy and it became a very dangerous place for Jews. If Jews were stopped in the streets by Nazis or Fascists, and they showed an identity card that labeled them as Jewish they could be sent to concentration camps. The Rabbi and Cardinal of Florence teamed up to help these Jews find shelter and false identity cards (which were critical for safety but could also be used to procure ration cards and food).

Gino became involved in this burgeoning new network through the Cardinal. They had been friends for several years. The Cardinal tapped Gino because he needed a postman to distribute the fake identity documents as regular citizens could not move around Italy during the war because there were military checkpoints everywhere. As one of Italy's most famous professional athletes, it was not surprising that Bartali frequently discovered fans among the soldiers manning the checkpoints.

We heard bits and pieces of this story on that May morning in the small but proud museum dedicated to Gino Bartali in his hometown of Ponte a Ema. There we also spoke with Gino Bartali's granddaughter Lisa.

"What I admire most of my grandfather Gino is his great courage and determination, not only during the races in his long career, but the courageous approach that he had in his whole life," she said. Lisa was very moved by how many people from different cultural and religious backgrounds had come together to ride to honor her grandfather.

I had been to the museum years ago while researching my book about Gino but for many of the Israeli cycling team, it was their first time.They wandered around in awe.

The Israeli Cycling academy has embraced Gino Bartali because they are profoundly grateful for how Gino helped Jews during World War II. But beyond that "we see Bartali as an inspiration for the next generation of cyclists," said Dan Craven, one of the oldest members on the Israeli team, and a former national cycling champion of Namibia. "Bartali carried the values that we want to bring to the world: sportsmanship, nobility and humility," said Craven.

Bartali was a scrappy underdog in many different points of his career and this quality appealed to the Israeli team. Created in December 2014, Israel's first professional cycling team was the brainwave of Ran Margaliot, a one-time Saxo Bank rider, who joined forces with Israeli businessman and cyclist Ron Baron. The team has progressed to the Pro-Continental level in just over three years. Now they have racers from over fifteen countries including Canada, Estonia and of course Israel.

After our brief stop in the Ponte a Ema, the group set off for Assisi, nearly 195 kilometers in distance from Florence.

For Gino, he would often start these rides early in the morning. First, he would stop by a secret rendezvous point, and pick up his precious cargo, usually photos of refugees that would be used to create false identity documents.

Then he would roll these up like a scroll, take off the seat of his bicycle and hide them in the frame.

As Gino left Florence behind, he would often wind his way along the strade bianche– the "white roads" that Tuscany is known for – flanked by vineyards and silvery green olive trees.

Sometimes Gino would do the trip in one shot, other times he stayed overnight in a church in Perugia. The final miles were among the hardest as Assisi is perched up in the foothills of the Appenine mountain range.

When Gino arrived in Assisi he would make his way to the San Damiano monastery to meet with a priest named Rufino Niccacci who helped run this wartime counterfeiters' network. Gino would drop off the new batch of photos, so that they could be transformed into documents.

Between Bartali's visits, two printers near the San Damiano monastery, a father and son named Luigi and Trento Brizi, worked with Niccacci and others to transform the materials Bartali dropped off into identity documents. Then Bartali would return to pick up the new identity documents that could be distributed to Jews hiding in Tuscany and the surrounding areas.

Our group finally arrived in Assisi in the late afternoon of May 16th and we were met by the deputy mayor of Florence, of course a Bartali fan. Assisi has recently opened a new museum called the Museo della Memoria or the Museum of Memory where Bartali figures prominently. We saw the old printing press that had been used by the counterfeiting network and the faces and stories of many of the Jews that had been saved.

In addition to the documents he ferried, Bartali sheltered a Jewish family, the Goldenberg family, in an apartment he owned in Florence. Their story is depicted here as well as the stories of many Jews who spent their time in Assisi during the war. The exhibit also showcases that Bartali became a Righteous Among Nations in 2014, the highest honor bestowed by the Israeli government on a non-Jew for saving the lives of Jews.

We toasted Bartali over dinner in an old convent turned into a hotel. As the sun sets on the red roofs and spires of Assisi, many shared their reflections about Gino Bartali. Two team members had also created a special video tribute to Bartali. (https://www.israelcyclingacademy.com/pages/in-honor-of-gino-bartali)

"For me it's easy to connect to Gino," said Aviv Yechezkel, an Israeli rider on the team. "He saved Jews. So he saved me."

"If we can motivate use Bartali's story to motivate just one person to do something for others, not just for themselves then it is a success," said Craven.

I was reminded of my conversation with Lisa Bartali, Gino's granddaughter, earlier that day. Lisa quoted a favorite saying of her grandfather's: "Some medals are pinned to your soul, not your jersey."

Aili McConnon is an avid cyclist and co-author of Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II, the Nazis and the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation. www.roadtovalorbook.com