Nyad completes Cuba-U.S. swim

Diana Nyad’s face was swollen with jellyfish stings and her speech was slurred with the painful toxins from the gelatinous zooplankton and the accumulated fatigue of a 52 hour, 54 minute swim from Havana, Cuba to Key West, Florida. The victory photo was no Vogue cover shot – it was more like the classic boxing photo of Jersey Joe Walcott’s face being squashed by the fist of Rocky Marciano. Not to forget that this International Swimming Hall of Famer completed this monumental adventure at 64, an age at which many people’s highest ambitions are to retire to the couch, collect social security and play shuffleboard in the sunset of their lives.

Instead, Nyad was girding herself to say a few words to the throngs who came to witness a landing which, in its small way, echoed the cheers that awaited pilot Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis airplane at Paris’ Orly Airport after making the first transatlantic flight in 1927. After all, this human-powered endeavor was the first time any human had completed the Cuba-U.S. swim across the treacherous Florida Straits without the protection [and presumed swimming aid] of a shark cage.

Nyad had three things to tell the raucous crowd that came to witness history. “One, we should never give up,” she said. “Two, you’re never too old to chase your dreams. Three, it looks like a solitary sport, but it’s a team.” Whereupon she was given an IV and taken away for a medical examination.

Most assuredly, Nyad had a team that rivaled a NASCAR factory shop and pit crew, a team that had been honed and perfected during her unsuccessful four tries at the crossing. In one of her more recent tries, she estimated in an interview that the total cost was in the neighborhood of $500,000. This time around, she had a team of 35 traveling in five support boats. The support crew included a medical doctor, a kayaker who kept pace with her and a crew of divers who swam ahead scouting for sharks, a meteorologist, and a satellite oceanographer expert on Gulf Stream conditions. Perhaps the key man was navigator John Bartlett, who charted the course with the aid of sophisticated satellite weather and ocean data.

After succumbing several times to the potentially deadly scourge of open ocean jellyfish, Nyad had her most sophisticated protective gear yet – a full bodysuit, gloves, booties, a protective silicone face mask and goggles, and the exposed parts of her face were slathered with a protective cream they called “Sting Stopper.” Nonetheless, Nyad’s face looked puffy and sunburned — from the jellyfish stings — and her lips were more swollen than a Hollywood starlet on Botox.

Risky business

No matter how much help she got, Nyad and all her team know that the enterprise is risky, tests the limits of human endurance and is very dependent on luck. In 1978, on her first Cuba to the U.S. attempt, she swan inside a 20 by 40 foot steel shark cage for 40 hours before doctors removed her because 8-foot swells were slamming her into the sides of the cage and blowing her off course. In August of 2011, at the age of 61, her handlers helped her back into the boat after 29 hours after incurring shoulder pain, a flare up of asthma triggered by box jellyfish stings, and strong currents had pushed her miles off course. She had utilized a paddler equipped with shark repellent, but the less dramatic threat of the jellyfish remained the biggest obstacle.

Her 2011 expedition proved a key to her ultimate success as her support crew developed technology designed to keep her swimming in a straight line. A 2011 Yahoo Sports online article described the apparatus as a “specially designed, slow-moving catamaran support boat [which] deployed a 10 feet streamer: a long pole keeps the streamer several yards away from the boat, and the streamer is designed to remain about 5 feet underwater, so that Nyad can swim above it, much like following a lane line in a swimming pool. At night, the white streamer will be replaced by a string of red LED lights.”

Her fourth expedition in September 2012 ended halfway as she was hit by armadas of Portuguese man-of-war and fleets of box jellyfish – and a lightning storm pushed her way off course.

In what Nyad termed her “final attempt,” several crucial factors lined up perfectly. Unlike the English Channel efforts where swimmers must endure sub-60 degrees waters and used to pack on fat and lather themselves in grease, Nyad says the much longer Florida Straits swim demands treading a fine line of much warmer temperatures. Nyad says that she needs a minimum of 86 degree water to begin her journey. That leads to dehydration, which must be warded off my constant hydration, but during the final half the warm temperatures of the Gulf Stream are crucial to avoid the even bigger threat of hypothermia.

This time around, the ocean surface was relatively calm, the currents were favorable, and her support was superb. Still, some jellyfish got through her protection and caused her lips to swell and her speech to slur and prompted concerns about her breathing. Nyad also told her crew that she was “very cold” and, as reported on her expedition’s blog, halted some planned feeding breaks overnight “in hopes the swimming would keep her warm.”

For most of her swim, Nyad stopped every 40 minutes for bites of scrambled eggs and pasta.

A short history of long swims

The first long swims that grabbed worldwide attention were crossings of the English Channel. Matthew Webb was the first across and made the 21-mile (plus extra for the tides and currents) in 1875 in a time of 21 hours and 45 minutes. It took 35 years before that feat was duplicated and took Thomas Burgess 22 hours and 35 minutes. Gertrude Ederle was the first woman, making the crossing in 1926 in a record-smashing time of 14 hours and 39 minutes. Yvetta Hlavacova set the current women’s mark of 7:25 in 2006 while Trent Grimsey set the men’s record of 6 hours 55 minutes last year.

Nyad started her quest for long distance swim challenges in 1974 when she set a women’s record of 8 hours 11 minutes for the 22-mile Bay of Naples race. In 1975, she set the mark of 7 hours and 57 minutes for swimming the 28 miles around the island of Manhattan.

In 1978, at the age of 28, she made her first unsuccessful try at swimming from Havana to Key West. In 1979, on her 30th birthday, she swam the 102 miles from North Bimini Island, Bahamas to Juno Beach, Florida. Thanks to favorable winds and currents, she completed the swim in 27 and one half hours and set a world record for distance swimming.

In 1997, Susie Maroney of Australia completed the Havana to Florida swim in 25 hours, surrounded by a steel shark cage which experts said both calmed the waters and provided artificial favorable currents which greatly sped her journey.

Some intriguing facts

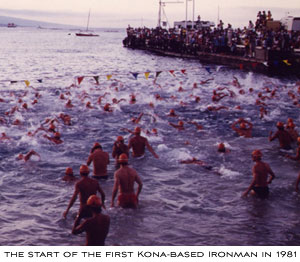

After one of her appearances on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1980, the president of ABC Sports, Roone Arledge, noticed Nyad and her penchant for storytelling. He offered her a position as an announcer for ABC’s Wide World of Sports and she was assigned to many of the early Ironman Hawaii broadcasts and provided insight into the extreme endurance challenges faced by the sport’s pioneers.

Many people notice that her last name, Nyad, is an offshoot of naiad, a Greek word referring to the nymphs in classical mythology living in and giving life to lakes, rivers, springs, and fountains. There are many other synonyms, including mermaid, siren, water nymph and sea maiden. The fact is she takes her surname from her mother’s second husband, Aristotle Nyad, a Greek land developer who adopted Diana and, in a fortuitous stroke considering her swimming destiny, moved the family to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the home of the swimming Hall of Fame.

By all accounts, she was gutsy from the beginning. Nyad entered Emory University in 1967 but was thrown out of school when she jumped from a fourth floor window wearing a parachute.