The roots of Jakes Triathlon

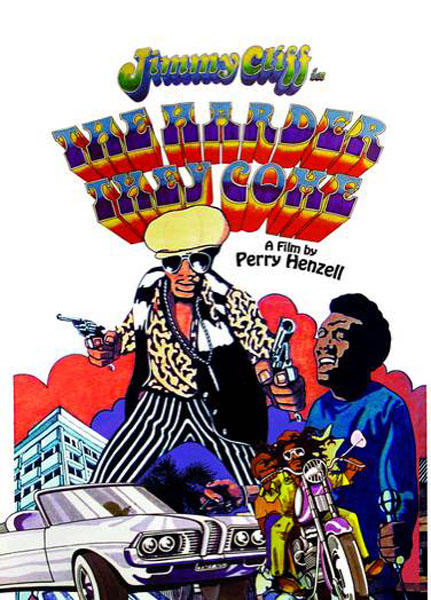

This is a story of several interconnected threads that wound together in a serendipitous confluence to make a small but enchanting triathlon called Jakes set on the south coast of Jamaica. The far flung threads required to weave this triathletic tapestry included a dashing filmmaker of the 1972 Jamaican classic film The Harder They Come, his wife, a talented artist, architect and poet, their son, a financier motivated by social improvement and community development, and a prominent triathlon race director from Southern California who became enamored by the Caribbean vibe, the people, and the beauty of the countryside. And lending his name to the whole enterprise was a parrot named Jake.

The back beat of this enterprise was of course the emerging internationally prominent sounds of reggae and ska. And much of the energy on view at this roots-oriented, bare bones triathlon comes from the joyous participation of triathletes from several continents mixing with local Jamaicans riding used mountain bikes and running up and down rugged off road trails carved into the hills of the beautiful ranches and farmland of Treasure Beach.

This story is not at all about modern big time triathlon with thousands of entries competing in the Olympics and at Kona in front of thousands of spectators. It's about a small race that captures and preserves the wide-eyed innocent joy of the first triathlon on Fiesta Island, the sense of rugged sense of adventure of John and Judy Collins' off road adventure triathlon in Panama, and the purity of those first Iron Man contests on Oahu.

Jim Curl, the co-founder of groundbreaking United States Triathlon Series, which established professional triathlon, and a member of USA Triathlon Hall of Fame, is a good guide to this story as anyone. Why did he come to work for a tiny triathlon in a hard to get to corner of Jamaica 15 years ago which had no more than 100 entries? And why after one year of trying and failing to boost this event into an international money maker, did he decide that this roots triathlon, with fearsome potholed roads and trails, was already perfect? And why was it worth his time, effort, and love for no salary – for the past 15 years?

Curl says his story began when a friend from New York turned him on to the sound track of The Harder They Come, “I didn’t see the movie for years,” says Curl. “But I knew all the songs by heart.” One of his favorites, sung by Jimmy Cliff, was “Many Rivers to Cross,” which he says serves as the theme of his long odyssey to Treasure Beach.

“There were many rivers coming together,” says Curl. “My river started back in 1983 when I was contacted by [original Escape From Alcatraz race director] Dave Horning who had been contacted by a guy who wanted to put on a triathlon offering diamonds in the Bahamas. It was called the Bahamas Diamonds Triathlon of the Stars. The guy who put it on was a diamond merchant/promoter. He was not a good guy. We didn't know that ‘til the end when we found out that all his promises did not come through. His diamonds turned out to be industrial B Grade which weren't worth close to the big prize awards he claimed they were.”

Scott Tinley won, and for reasons still murky, Curl was pulled off his plane and thrown in jail. “The good that came out of it was the start of my real interest in the whole Caribbean culture in ’83,” he said. “I had a chance to go back again when Renny Roker and I started up an event in St. Croix called America’s Paradise Triathlon. At the first year in 1988, we had NBC TV and all the greatest triathletes in the world – including Mark Allen, Mike Pigg and Paula Newby-Fraser. They had a $100,000 purse and Dionne Warwick sang the Star Spangled Banner a capella It was an amazing event and it confirmed how much I enjoyed the Caribbean.”

In 1992, Samuel McCook of the Jamaica Tourist Board contacted Curl and they became good friends. “A couple years later, he asked me if I would put on a promotions conference in Kingston called Caribbean Sports and Special Events. We did that from 1993 through 1995. Because of my connections in sports, I could bring in some amazing people in public relations and television. From that, I worked with the JTB and was contacted by Chris Blackwell (of Island Records fame), to put on in ’96 the James Bond Jamaica Festival. We brought in Ursula Andress – “Octopussy” – one of the Bonds, Grace Jones and the actor who played Jaws, Richard Kiel. He was a huge guy, a very gentle man. We held it in Ocho Rios; the same place they filmed Dr. No. We had the biggest party at Ian Fleming’s estate. at a place called Golden Eye on Oracabessa Bay on the northern coastline. It was owned by Blackwell, whose Island Records was behind Bob Marley. But that’s another story.”

The James Bond Jamaica Festival was an artistic success but a financial flop. But it caught the attention of some guys in Kingston who wanted Curl to help start The Reggae Marathon in Negril, Jamaica. Ever the showman, Curl began the race in pre dawn dark with African drums beating and bottle torches lighting the start. It was big success and he worked on it for a few years and caught the attention of a man who ran a little triathlon in a resort about 3 hours southeast of Negril. That man was Jason Henzell, son of Perry Henzell, famed for directing the ground breaking hit film The Harder They Come.

In 1991, Jason decided to make a small triathlon as a favor for Peace Corps volunteers and with Amy Gottlieb they started it in 1996, five years after Sally spearheaded and founded Jakes Hotel and Restaurant in Treasure Beach. In those formative years, Jason offered his financial expertise and investment skills for the expansion of small resort hotel his mother designed and hosted. “As time went on, I wanted it to grow a little so I went to see The Reggae Marathon in Negril which was organized and run by Jim Curl,” said Henzell. “I saw Jim in action and he was like a drill sergeant. I mean it in a good way. He was in control. The thing about a race is that as much as it is fun and you want people to have a good time, you want it to be safe. You need someone very strict, very structured. He was screaming orders at people and I looked at him and I thought, ‘That's my guy! I need to get him down to Treasure Beach.’”

When Perry Met Sally

Back in the early 1960s, Perry Henzell was working in a Kingston advertising agency when he met a new office worker, 18-year-old Sally Henshaw. As she said, “sparks flew.”

Both were from well off Jamaican families. Sally's parents were wealthy Scots whose family came over when one of her uncles was sailing someone else's yacht around the world when the stock market crashed in 1929. When he got to Kingston, he telegraphed his brother: “Come over – and bring the polo ponies.” And so her father Basil arrived and married her mother Joyce and they settled near Kingston. Sally was born in Mandeville, about 90 minutes inland from Treasure Beach. In 1941, her father built a family vacation home there called Treasure Cot, where she and her sister would swim and fish and walk with friends along the beach that was just a short walk from the bit of land that would become Jakes.

Perry's paternal grandfather, descended from Huguenot glassblowers, was married to an old Antiguan family, while his mother hailed from an established family in Trinidad. Perry was born in Port Maria Jamaica, about 12 miles outside Kingston on the Caymanas sugarcane estate. Perry rejected his privileged status quickly. Sent at 14 to an English boarding school, he decided to hitchhike around Europe instead.

After he was rejected by the BBC drama department, he returned to Kingston in 1959 and began directing innovative commercials. And after marrying Sally and a decade of TV work, he set out to create The Harder They Come with co-writer Trevor Rhone.

The movie adapted the story of Ivanhoe Martin, a real life Jamaican criminal killed by police in 1948, grafting on serious points about harsh realities facing migrants from the countryside in the island's dehumanizing capital, the exploitation of talent by execs in the burgeoning music industry, and the lure of the booming marijuana trade. Reggae star Jimmy Cliff played the lead – Ivan O Martin – as a man of pride who would bow to no one on his drive to make it in the music business man. He died heroically in a hail of bullets.

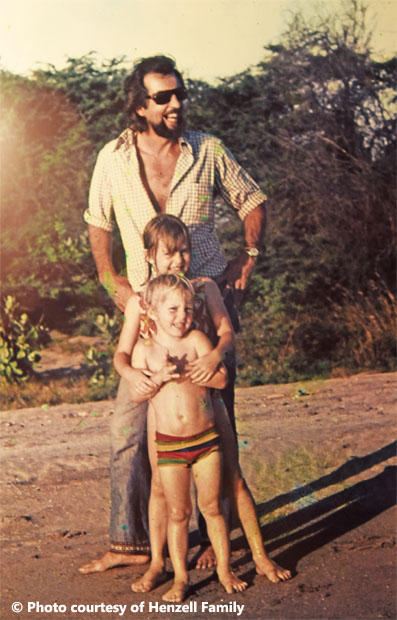

Perry went on the road to sell it the film on the international market, while Sally, who had served as the movie's art director, tried to regain a semblance of equanimity by retreating to Itopia, an isolated stone villa on the north coast of Jamaica with no telephone, no lights. “That is what I wanted because during the movie Kingston was a bit like the Wild West and all those same people in the film were in the movie and would not leave after it was done. They had made a little nest in our house. At that time, our daughter Justine was 10 and refused to leave her school and friends in Kingston. But Jason was just 5 or 6 and I put him in my pocket and took him with me.”

Sally spent most of the next two decades at home with Perry, whose writing career flourished in isolation. In 1991, she was visiting her family's cottage on Treasure Cot. (where Arthur Haley wrote a big piece of Roots). Sally recounts a fateful meeting on the beach: “I am walking past this place and somebody said, 'You know it's for sale?' I said, 'Is it? How much is it'?' I went next door and found out how much it was. My parents had just died and I just sold their house. The down payment that was practically in my pocket was the exact amount that they asked for this piece of land.”

She bought it and soon thereafter her son Jason bought property on either side and Sally planned to fix up a tiny little four room house for Perry and Sally and their two children. “And then one day after mucking around in the sun and the prickles and the broken glass and God knows what, we went down to the only restaurant in town for dinner,” said Sally. “At 11 o'clock that night we still hadn’t got dinner. They had forgotten us. I always had it in the back of my mind that I saw myself owning a restaurant. And then I said, ‘Oh this must be it. There is no food in this town.’ So having decided to turn this place into a restaurant, I then had to get out. And so I built this two more rooms and that is how it started."

Soon thereafter Jason quit his banking job to run the business side of things. “And he had the good idea to buy next door,” said Sally. “As Jason kept buying, I kept building. My husband had sort of prophesized that I was going to do a lot of building. Because I had done some for us. I built a couple rooms on to our house. And I built a cottage for myself. Perry saw in me a career as a builder, although I had never been trained as an architect.”

By 1991, Sally had plunged full bore into designing and basically art directing Jake's Hotel and Restaurant's every detail into the casually beautiful place it was to be. As time went on, she designed separate villas to the west of the main building in the manner of Antonio Gaudi, each painted in the bold colors of the Caribbean.

The Partnership begins

Henzell called after The Reggae Marathon, and went to Treasure Beach and met the Henzells. “I was impressed because I thought it was a pretty cool thing,” said Curl. “They were looking for someone to work to grow the event to make it international class. So I said, ‘OK I’ll take the chance I can make money on it; You won’t need to pay me.’ I would do it for the potential for profit the race would create and try to make my money that way. Turned out the nature of this event just wasn’t amenable to being turned into an international event at that point. It just wanted to be what it was – this incredible roots, back-country experience of athletics and the country of Jamaica. After my first year, I was kind of crushed I didn’t get the numbers I wanted. I didn't get the sponsors I wanted. Then I was sitting at the awards ceremony and seeing the joy that people had at that event, how much fun they had coming together for this little triathlon. Then I realized this is a huge success. I don't want to change this. I need to preserve this feeling. I needed to figure out a way to raise money for their charity – Breds – but not necessarily turn it into grandstands and PA systems and pros – that whole thing I had come out of with USTS and World Championships.”

That first year might have been enough for most race directors. But the reason Curl stayed was the bond he felt with Jason and Sally. "When I met the Henzells and became friends and co-workers with them on this deal, it is one of those things that is hard to explain to people because they don’t fit into the usual boxes. Perry died in 2006 but Sally is the most the most amazing person I know. I love Sally. She is about 70-something years old and has twice the life of anyone you’ll meet – and she is very creative. You can see it with the all the flags she assigned the local school kids to make last year so we could hang them over the street. She has an amazing eye. She designed half of all the art for the resorts in the area. And every detail of Jakes – her masterpiece.”

Curl sees Jason as the man who can get things done. “Nothing would have happened without Jason,” says Curl. He realized if Treasure Beach went the way of all the other beautiful places such as Ocho Rios, it would be destroyed for what it was. But it had to grow to give people jobs so they could sustain it.”

As Curl explains, it would be supersized and franchised and when that happened you would know that special thing is gone. “At the same time, if the cook is not getting paid, your special place is over. So Jason is the Baron, the Young Prince, the guy behind everything in Treasure Beach. In this situation there has to be someone who has the juice to get things done and that is Jason. He works really well with the community. He works really well with the charities. But it is Jason’s vision that Treasure Beach can get enough sponsorship. And with enough of the right kind of vision, it can grow with sports tourism and community tourism. With these things, people can have a good time, grow and people can have good lives. And Treasure Beach will still retain the essence of what it is. Which is a tiny little Jamaican town where everybody knows each other. Everybody leaves their doors open, and there is literally no crime.”

Jake's Triathlon and the future

Curl says there is nothing wrong with seriously competitive international triathlon. “But I thought there was enough seriousness in ITU, Ironman and Challenge,” says Curl. “Jake's was about the pure joy of the sport, the people, and the experience. The personal challenge of it. There’s not much more than that – and that is plenty. When I realized that I thought this is what I'm going go do. I am trying to grow it slowly.”

In his years in triathlon, Curl has come to be a connoisseur of roads, and he loves the ones at Jakes. “To me there is nothing more beautiful than a road full of potholes filled with a herd of working goats from a nearby farm. And that is Treasure Beach, the South Coast of Jamaica. When they put a black ribbon of new macadam – all smooth and slick – it is not nearly as evocative as a dirt road.”

As for the challenge, the 12 and half miles on Jake's bike leg includes an 8/10ths of a mile ride up Groun Hill with roughly as much elevation rise as The Beast in St. Croix. Only this climb winds around and through gullies and rocky moguls and off camber dirt corners with loose soil which begs for traction. All in the 80 to 90 degree heat under the rising sun. Some of the potholes and square edge bumps on the pavement beg for attention, as some of them some on bobsled-steep downhills with 90-degree corners at the bottom. Yet, as thrilling as these sections are, the heat causes more problems and the safety record after 20 years is pretty good, said Jason Henzell.

“We only had two serious accidents in the 20 years,” he said. “One was a bike accident [before Curl came into the picture]. The other was a guy who was running and fell down from heat exhaustion. They had to give him seven bags of drip. He passed up all the water stops and didn’t take any water. He was competing with his brother who was behind him and I think he was showing off that he didn’t have to have water.”

While Jakes won't attract Javier Gomez any time soon, there have been some world class Jamaican athletes performing at a high level. “If David Bromfield races, David Bromfield will win,” says Curl. “ He is a world class duathlete who could not get his visa to go anywhere. He is not much of a swimmer but it is only 300 meters. He is a really good runner, a really good cyclist – and look at the strength of him. He has mastered the hill that is called Big Groun. It is an .8 of a mile climb at 6-7 percent. He just goes and he is either in the lead or he is on your tail and it is all over.”

Even the local kids can run like the wind and take down many an international amateur, which delights Sally Henzell. “I think 9 times out of 10 it is a young Jamaican guy who wins. Beats all these high falutin' people who have done it all over the world – blah blah. And this little skinny guy ends up winning – David Bromfield.”

One Jamaican triathlon international has competed here and won. Iona Wynter-Parks finished 13th at the 1999 Pan American Games and 34th at the 2000 Olympics. “Wonderful gal,” said Curl. “A great cyclist, she was the kids race director here for years and almost won the whole thing herself one year. If she shows, she wins.”

While Jamaicans are generally ultra competitive, everybody's favorite Jakes story is all about sportsmanship. “One guy from out of country had a flat out on the course and this local guy rode up beside him on a motorcycle and took out a knife,” recalls Henzell. “This poor foreigner thought this guy is gonna’ rob me and this is the end of it. But the motorcycle guy took the knife and cut off a piece of his seat. And he took the tire off the bicycle and sat down beside the guy and made the patch out of a piece of his motorcycle seat. The guy who thought he was being held up at knifepoint was actually aided and assisted. I keep saying I don’t know if it would be perfectly legal by the triathlon association. But who cares? What we are really doing is building community one story at a time. One biker at a time.”