Wrapping Up Our Sports Nutrition Series

For years, we have believed that ninety grams per hour is a seemingly mythical upper limit to safe and useful carb consumption in triathlon and any other sport that’s crazy enough to suffer for three, four, or twelve hours. There have always been whisperings that maybe it’s the limit, but they slip through the cracks and don’t lodge themselves in our memories.

The concern most of us share about consuming too much carbohydrate in training is that it will mess with our gut, so we aim lower to be on the safe side. It’s a delicate balance of avoiding the portaloo while keeping blood sugar elevated enough to enhance performance. Balancing GI issues, and not bonking. It has been treated as sacrosanct that if you do manage to consume 90 grams per hour, your only risk is gut discomfort, and certainly not hypoglycemia and bonking.

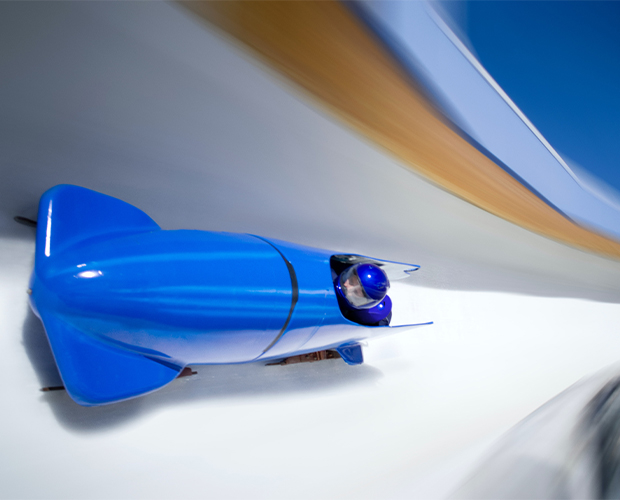

But take a man whose profession it is to sprint for 5 seconds, twice a day, while pushing a 600 pound sled, and seat him on a 15-year-old entry-level Trek road bike for six and half hours. The result of putting a gorilla of a bobsledder on an old bike for his first century ride in 15 years? New levels of hypoglycemia and hunger, even with industry shattering high carbohydrate consumption rates. He was able to avoid GI distress and still managed ongoing hypoglycemia while consuming 117 grams of carbs per hour, even though his record-low aerobic fitness provided him little capacity to burn energy

Without any gut training, those carbohydrate consumption rates were a powerful neutralizer to the industry dogma that 90 grams per hour was a nearly mythical ideal that works for everyone doing endurance sports. A disastrously unfit person with no gut training managed to achieve hypoglycemia and no gut issues with 117 grams of carbs per hour. Either he happened to be a bizarre double-outlier in his ability to burn carbs with no aerobic fitness and to avoid GI distress at absurd fueling rates, or there must be some holes in the literature.

This spawned a deep dive into the literature for the benefit of us all. I had to know. And this deep dive into decades of fuel and hydration research was with relatively fresh eyes, since I’d been mostly uninterested up to that point in my academic career.

Those fresh eyes were also highly motivated to understand all the factors at play. The bobsledder was me and this is my story.

Years of anaerobic training came with a humongous ability to burn carbohydrate and virtually no fat oxidation ability. Friendly reminder: “oxidation” means burning the stuff as fuel for your body’s energy output. I had no fitness, and thus virtually no capacity above resting metabolic rate to use fat as fuel. Whether you’re in the keto camp or the high carb zealot camp, or somewhere between, it’s generally agreed upon that high fat oxidation ability is a key performance indicator for endurance sports.

The ability to burn fuel aerobically is key for endurance sports, and I’d trained and “sedentary’d” my aerobic fitness away long ago, as most bobsledders do. In case you’re not familiar, being intentionally sedentary outside of training is performance enhancing in speed-strength sports like bobsled. It also takes aerobic fitness to all-time lows.

I was coming off an almost four year post-decathlon stint as a professional bobsledder. I was 6’1”, 225 pounds and 10% body fat. I squatted nearly 500 pounds and snatched almost 300. That’s the one where the barbell goes floor to overhead in one swoop. I bench pressed 400 pounds.

I looked like it. And most of all, when I was on that Trek, I felt like it.

I had broken my foot 6 months before the 2018 Winter Olympics and went from being an Olympic hopeful in bobsled and idle bystander in Michelle Howe’s triathlon & cycling pursuits, to trying dearly to hold her wheel, overnight. Cycling was the past love that I immediately rekindled upon retiring from professional speed and power sports.

I knew from past exploits a decade earlier (on the same Trek 1200), if I rode that century, I was going to be hungry. I thought I knew from preliminary research that 90 grams was the upper limit for most folks. But I was desperate and knew that this century was going to be as much of an eating contest as it was a pedaling contest. So I packed what I thought would be overkill. More than possible to consume.

I finished in 6 hours 30 minutes. It took all of me. I had roughly a 2.0 W/kg FTP at the time, and there was a 10% grade hill where I distinctly remember that my bike momentarily rolled backwards between a couple of my pedal strokes. My cadence was momentarily negative. Yikes.

For the fateful ride, I had planned to consume whatever my gut would allow. I did just that. And I was absolutely ravenous at many points during my ride and even more so at the end of the ride.

Here’s what was consumed:

~115 grams of carbs per hour

2 unaccounted for snickerdoodle cookies. Possibly other things.

800mg caffeine (see: bobsledder)

~7000mg sodium

Untold liters of water. I lost count by 40 miles in. I was already in a world of hurt. This was roughly 30 miles before the “did I just roll backwards?” moment on the hill.

~500 Calories per hour.

It was in the middle of that ride that I realized over and over that I wished I had carried more carbohydrate fuel with me. Hypoglycemia doesn’t even begin to cover my experience. The crash was real.

Counter to every major textbook and position stand by a major sports nutrition journal, I could have, and would have happily, used more fuel. By the time I finished my gut was absolutely empty. Achingly empty. Craving calories empty. I experienced no problems with gut clearance, gut cramps, feeling full, sloshy, nauseous, or burpy. I felt fine. Just ravenous and thirsty.

That said, for many folks, intimate personal experience with gut issues makes them leery of coming anywhere near these fuel intake rates.

However, it was during the ride that I realized that 90 grams per hour absolutely had to be hogwash as the upper limit of utility for a lot of folks, and it most certainly was hogwash in terms of gut tolerability.

I either had to have been an outlier of outliers in gut tolerance ability, or the research wasn’t as clear cut as it seemed.

The problem had to be an implementation and strategy problem, and I was dead set on figuring out what I’d done that had allowed such high intake rates in the face of a decade of convincing claims that nobody’s gut could tolerate more than 90 grams of carbs per hour. It turns out, there have been those kinds of anecdotes of high capacity to intake fuel since the 1980’s. They’ve largely been ignored by the scientific community. The herd mentality has been strong among my scientific peers.

I could have, and would have happily, consumed more fuel throughout the ride. I believe I’d have been able to go faster if I’d had it available. And I had exceeded the current day industry standard, increasing the upper limit of carb intake by 25 grams per hour, or almost 30%.

Sure, I was a special case in terms of carb oxidation. I was indeed an inefficient carb-burning gorilla. But my gut wasn’t special. Guts aren’t larger or more absorptive just because you bench press lots and eat pounds of protein every day. I had done no gut training. I hadn’t monitored my glucose:fructose ratio (something that is typically stated to be of critical importance when approaching even 90 grams per hour, let alone 120 grams per hour), and I had just used plain sugar. Almost 1 quart of plain sugar, mind you.

A whirlwind of a year later, I co-wrote a book on fueling and diet for nutrition athletes. It's a little out of date by my standards now, but by industry standards it’s still a decade ahead.

Together with my beloved contrarian wife, Michelle Howe, endurance coach and dietitian (who reads all my work, and pokes dozens of holes in my claims, my memory, and my stories, and is always right), I hope to negate the need for reading that book by giving you all the need-to-know and most up-to-date information on our YouTube channel and through articles like this one, and the many that follow. We’re working hard every day on an app that also does this all for you and coaches you to the right fuel.

Most importantly, during that year of reading and writing, while consulting a growing number of endurance athletes on their race fueling plans, I began to have a clearer view of the landscape of the endurance sport nutrition world.

Since that fateful year, my endurance fueling research has exceeded my doctoral research area in both professional experience and education, and Michelle can still argue me into the ground on virtually any fuel & hydration topic she chooses. That’s saying something, since I was a professional bobsledder, I built a bobsled training facility, and my 300-page doctoral dissertation was on how to push a bobsled faster. Michelle has gone pro in triathlon, placed top 5 in the country in the pro nationals time trial, and become a board certified specialist in sport dietetics. Suffice it to say, we’ve taken a few steps forward out of the fuel & hydration darkness from our days of riding our aluminum Trek’s with obnoxiously unlubricated chains.

We hope to bring our learnings to your world of fueling & hydration so that it’s a little more clear, accessible, and most of all, simpler and easier to do right. Especially when you’re just getting started. It shouldn’t be the black box that it was for me when I first made the switch to endurance sports. The research is clear. There should absolutely be some personal trial and error, but it shouldn’t be clouded in fear, doubt, and uncertainty.

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network