Heart Tired revisited

This Heart Tired story was originally published on slowtwitch on 02-07-2000 and given its relevance today we though we should bring it up front again.

"The only guys I ever knew who’d get heart-tired were the Germans. Nobody would do the amount of work they did," says longtime American pro Mark Montgomery, probably the first American to train regularly with such early German stars as Jurgen Zack, Wolfgang Dittrich and Jochen Basting. Montgomery was talking about a little-known malady—a type of over training in which the heart is unable to beat at a rate high enough to do the work required.

"The Germans would do so much work, their legs were so strong, they were so fit—they were the only ones who could outwork their hearts," Montgomery says. "They’d eventually get to a point where they couldn’t get their heart rates up any more. Whenever that happened they’d train really easy—everything was below 110 beats per minute, and it might take them three weeks before their hearts came back. They would always just keep their work down [until] they recovered."

Most recreational athletes are more used to the notion that an elevated heart rate is the sign of over training, specifically during rest, and they’re right in their thinking. Fewer athletes are aware of, or ever experience, a heart that cannot beat fast enough. But professional triathletes are very aware of this phenomenon, especially those who engage in Ironman-style training and racing.

"There are days that I just can't get my HR to the zone I want it to be in," says Ironman and World Champion Karen Smyers. "This is a sign of not being recovered, and I reschedule the hard workout planned for that day. If you recognize it early, you can usually recover in a day or two. If you have pushed through it for a long time, you may need a much longer time to pull yourself out of the slump." Every triathlete who has done the big miles can relate to a time when the heart for some reason won’t beat fast enough under load. What is in question is exactly why this happens and what the physiological mechanism behind it might be.

Dr. Edgar Fenzl is an avid triathlete. He’s also one of the most respected clinical researchers in Germany. He knows all the German athletes and many of the Americans. And he maintains that the heart doesn’t get tired. "The heart is an amazing thing," he says. "You can do anything to your body you want—you can exhaust every muscle you have, you can work yourself even to the point of passing out, but your heart will keep beating."

Fenzl is like every doctor interviewed for this article. There is no basis in theory, nor any reported studies, in which the conclusion can be drawn that the heart gets tired. Yet there is not one top Ironman-distance pro who cannot relate to the experience. That is not to say that Fenzl and the other doctors do not recognize the symptom; they simply believe it is a metabolic or electrophysiological problem. The heart has run out of something. Perhaps there is a deficiency in ATPase or a certain electrolyte.

The problem is also one that is not always noticeable. "You won’t know you’re heart-tired without a heart rate monitor," Montgomery says. "You feel OK, more or less, it’s just that you’re out there doing an amount of work that should have you up to 150 beats, but your heart is only at 125. Your heart rate monitor is the only way you’ll know it."

While triathletes are the most likely to get heart-tired, long-distance cyclists can relate to the experience as well. "I was doing RAAM Relay one year," says Pete Pennsyres, winner of the Race Across America and holder of several long-distance records. "Every day I felt fine, but I had my heart rate monitor on and I found that I couldn’t get my heart rate up to the level sustained the previous day."

Perhaps it is a lack of something needed that creates an environment in which the heart cannot beat at its regular tempo, or perhaps triathletes engage in so much more aerobic work that the heart finally reaches the limit of its incredible endurance. Either way, Scott Tinley sees it this way: "Bottom-line is that we are living lab rats who are working without a net. We [triathletes] are peerless, without precedent and subject to long-term maladies about which nobody knows. The body is an amazing piece of machinery. I am afraid a few of us may have found the limits of long-term endurance training. This is an area that warrants further study. I did quite a bit of research in this area and basically found little if anything specific to LONG-term over training.

"You can get away from it for awhile," Tinley says. "Two to four years, depending. But after a while it catches up. The warning signs are subtle, varied, and easily masked by an athlete’s determination. The interest in Ironman distances, and the money and sponsorship, are the carrots that drive those who have the basic tools to be competitive." But Tinley also agrees with Scott Molina that, "It is underlying obsessive/compulsive behavior that fuels the fires. The damage that can be done varies on the individual. Everybody has a breaking point. Mine was the neuro-endocrine system."

Whatever causes the heart to slow during exercise is reversible. Longtime pro Ironman racer and current coach and clinician Ray Browning says that perhaps the heart is protecting itself. "Most athletes are aware that a sign of over training is an elevated heart rate at rest, and they project that notion into the belief that it will be elevated during training as well. But that’s untrue. I don’t know the mechanisms behind the dissociation between heart rate and perceived effort, and when I talk about that phenomenon people’s eyes glaze over. But maybe it is the body’s way of protecting itself from damage." Browning wonders whether there is only a finite amount of hard work available to all of us. If so, maybe this is the body’s way of protecting us so that we can live to fight, or play, another day.

Paul Huddle remembers the great Ironman racing days when, after you’ve given your heart and body all the rest it needs, it is able to beat 10 beats faster than in training. Most of us are used to the idea of protecting against a higher than target heart rate. While a low heart rate at rest is quite desirable, the heart’s ability to beat at its normal high rate is a sign of its health as well.

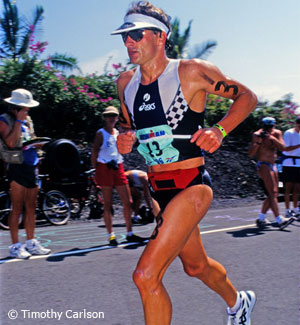

Image 1 is Wolfgang Dittrich, and image 2 Marino Vanhoenacker this year in Kona