Training, Adapting, and Racing in Heat

Old-timey medical researchers got a lot wrong. They also got a lot right. And in 1916, Frederic Lee and Ernest Scott started off a paper with the sentence, “It is a fact of common experience that a human being in a hot and humid atmosphere feels a disinclination to perform muscular work.” I’m guessing something similar has entered your brain at mile 17 of an Ironman marathon.

I’m not exactly discovering general relativity here. Obviously racing in heat and/or humidity slows you down. We all know that. But what is really going on in our bodies, and how do we mitigate its effects on race day? Well now, that’s where things get interesting.

When we’re exercising, our bodies produce heat. The warmer our environment gets, alongside a continuous increase in the intensity and/or duration of exercise, the slower we shed heat. Heat accumulates in our bodies and body core temperature continues to rise at a rapid rate. Humid environments are also a problem due to one of our body’s main cooling mechanisms: sweating. The idea is that a little bit of heat from our body is required to turn sweat drops into water vapor, and so that heat leaves our body when our sweat evaporates. This is great in less humid environments where water evaporates more readily. However, in a humid environment where the air is already saturated with water, there’s nowhere for our sweat to evaporate to, so it sticks to our body and doesn’t serve a meaningful cooling function. Your body keeps producing sweat to try to cool itself down, but all it ends up really doing is dehydrating itself. Beyond dehydration, this is a problem because our bodies like operating in a narrow internal core temperature band.

When we leave that narrow band, enzymes stop working properly, intracellular reaction rates change, and all sorts of bad things happen that aren’t necessarily compatible with peak performance (or “living”). Additionally, muscle glycogen depletion speeds up in hot conditions, which is a problem because oxidation of carbohydrates in the gut slows down in hot conditions, so it gets harder to replace what your muscles are burning.1 And then you end up curled up in a ball on the side of the road. Bottom line- when you are performing intense exercise in the heat the available fluid in your body must be shared by the muscle (to maintain performance), the heart (to maintain blood pressure and stroke volume) and the skin (to cool you down). When you are dehydrated this stresses the system even further.

Now, what temperatures are most relevant to us on race day? Core temperature. When I talk about “core temperature,” I’m referring to internal temp of your abdominal and thoracic cavities (i.e. your belly and chest). There are several modalities at your disposal for managing body temperature, and it’s up to you to practice them and have them in your toolkit on race day. Your main options for reducing core temperature in real-time are to slow down, move into less extreme environmental conditions (ex. shade), take in fluids (ideally supplemented with electrolytes), and/or reduce skin temperature.

As it turns out, the gradient between skin temp and core temp is one of the most important factors in determining performance losses due to heat. This is due to the way your body tries to shed heat. When you start overheating, arteries in your skin dilate to encourage blood flow. This is based on the idea that blood will get cooled when it travels to your skin, and as long as you have sweat evaporating and/or the external air temp is well below your body temp, then this works pretty well. A big problem for racing is that more blood going to your skin means less blood going to your muscles, which means reduced performance. So, if you can get your skin cooler, then not as much blood has to go there to get sufficient cooling power for your core. Your temps stay down, and more blood goes to your muscles. Pretty simple concept, right? However, having the means to do this during a long race is another matter.

To stay in that narrow core temperature band, we do things like shivering, sweating, dilating arteries in some areas and constricting arteries in other areas, etc… However, when you’re racing in 85-degree air with 80% humidity, those internal thermoregulatory tools often aren’t adequate and something’s gotta give – and usually, it’s your performance. The good news is that we can improve those internal thermoregulatory devices via training and intentional practice. We also have behavioral options available, such as clothing, pacing, fluids, etc.

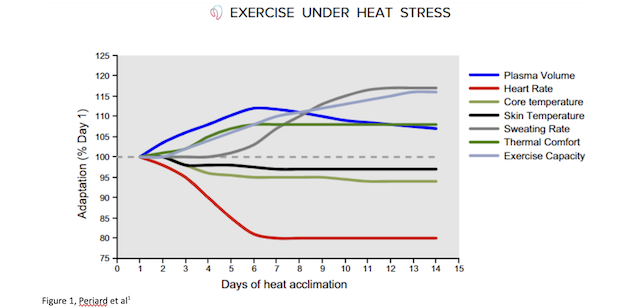

The physiological changes we can use to our benefit are going to be gained during daily life and race preparation in extreme environmental conditions – whether through exercise or at rest, but you will trigger the most effective adaptations during exercise in hot and humid conditions that gradually progresses in exposure.1 Post-exercise heat immersion in a sauna for 30-40 minutes can also be quite effective.1 Heat adaptations appear to benefit performance in all environmental conditions1, and if you can’t get the benefits of living at altitude, then the benefits of doing focused heat work are a pretty decent consolation prize. This figure summarizes a typical timeline for the various adaptations associated with heat adaptation.

Very important note here: I am NOT giving any sort of recommendation to do “dehydration training.” There are no adaptation benefits to dehydrating yourself during heat work, and all you’ll really be doing is putting yourself at risk of serious injury and/or death. This is part of the reason I have all of my athletes practice their race fueling plan on any sessions longer than 45-ish minutes. Not only do I want to make sure the session isn’t nutritionally compromised, I want to burn the fueling plan in their skull and I also want them to learn how to make adjustments on the fly to account for environmental conditions. So if you are doing any heat exposure work, be absolutely certain to drink more fluids than usual, consider adding an electrolyte mix to your drink, and be prepared to slow down or pull the plug on your workout if sense things are going sideways. Getting stronger and performing well in the heat is good. Exertional heat stroke is bad. Death is worse. Don’t be an idiot.

Heat training also requires a good amount of self-confidence and not caring what your numbers look like. I say this because Strava is a thing, and people like to have impressive looking pace/speed numbers on Strava so they can get more likes (semi-related note: social media is a wonderful tool for making people neurotic). So you need to have the self-confidence to go out and do heat work, and accept that your workouts are going to look “slow.” You have to be able to ask yourself this: “am I training to be strong and fast on race day? Or am I training to get Strava KOMs and convince my 84 Strava followers that I’m fast?” If you’re like me, it’s the former.

I think you’ll find a hundred different protocols for heat work, and I’m not here to go through all of them. They all boil down to basically the same thing: get out and train in heat stress conditions 4-6 days per week, and you should be pretty well adapted after 2-3 weeks. After you achieve adaptations, you’ll lose them at a rate of about 2-5% per day for every day you’re not exposing yourself to heat stress.1 My basic strategy is to do my runs outside at the hottest time of day possible and do my bike rides on a trainer with a shirt on and the fan on low. I’m sure it’s not perfect, but it seems to get the job done. If you can’t get out at the hottest time of day, then just wear a little extra clothing. Here are the general guidelines I use for heat-specific work:

-if it’s above 80 deg, just wear whatever you want

-if it’s 70-80 deg, wear a thin long sleeve shirt and gloves

-if it’s 60-70 deg, wear a thicker long sleeve shirt, gloves, and a thin wool hat

-if it’s 50-60 deg, wear tights, a thick long sleeve shirt (or a running jacket), gloves, and a thin wool hat

-if it’s below 50, then bundle up, baby!

And in all of those situations, I’m drinking extra fluids.

Also, as an additional note, being tanned for race day is not going to help you resist the heat impacts of solar radiation. All it will do is reduce the amount of sunblock you need to apply (note: sun block does not mitigate the effects of heating from solar radiation, either). And no, skin color doesn’t have much impact on the warming effects of solar radiation, either.2

Ok, so we’ve covered physiological adaptations for dealing with heat. But what about race day? As you can probably guess, the basic behavioral choices you can make on race day should be focused on cooling the skin. Methods of cooling your skin are as follows: keep the sun off of it, put cold things on it, and allow it to sweat. Solar radiation is funny: it doesn’t increase the air temperature, but it heats you up when it hits your skin. Want proof of this? Go out on a sunny day and stand under the sun. Then go stand in the shade. The air temperature in the two places is exactly the same, but one feels much cooler than the other.

Keeping the sun off it is simple enough: just wear clothing that covers your body. Oddly enough, the color of the clothing only makes a small difference, but the reflectivity of the fabric does make a big difference.1 But wait a minute… if you wear clothing, then that can trap warm air and/or impair heat loss from sweating by retaining fluid. Dangit! Much as your body is forced into a competition of diverting blood to muscles or blood to skin, your brain is confronted with a dilemma – do I want to keep solar radiation off my skin or do I want to maximize heat loss via sweating? The Bedouins in the Sahara desert have a nice solution to this, in that they wear flowing robes that both keep the sun off and allow airflow against the skin. Unfortunately for us, those robes are an aerodynamic disaster on the bike and would lead to horrible chafing when they stick to your sweaty skin during the run. So “loose flowing robes” are out for Kona, but we are getting somewhere.

What I’ve found to work well for me is a very thin, white, long-sleeve top with some reflective fibers in it and a tiny bit of ventilation. I’ve always raced well in the heat (save for IM Coeur d’Alene 2015 and Challenge Aruba 2017, but hey, nobody’s perfect, right?), and the top I’ve found best for this is the Skins A200. (Note: Skins was my apparel sponsor for a few years, and that’s when I fell in love with their products. That said, I’m sure there are several other companies out there making comparable products.) Here’s what you get with a top of that style: 1) white, reflective, fibers are good at repelling solar radiation; 2) it’s very thin so it doesn’t retain much fluid and you still get evaporative cooling from sweat; 3) it’s very tight so it can hold ice from aid stations against your body. I think you can achieve similar results by wearing a traditional tri top (short-sleeve or sleeveless) and white arm sleeves.

Important note: the efficacy of this clothing is greatly enhanced by keeping it wet and/or full of ice, so get greedy with the ice and water at aid stations! I’ve also had good luck with tube socks around my neck. It actually works quite well: leave T2 with a long tube sock and fill it with ice at the first aid station you see. Then tie a knot in one end and drape it around your neck. After it melts, fill it again with ice at another aid station. This is particularly effective because you’re putting ice right next to your carotid arteries and jugular veins, and so a lot of blood is getting cooled down very rapidly on its journey to/from your core. It can also be effective to get ice down your shorts and have it against your femoral arteries, but it’s much harder to keep the ice in place down there.

Other behavioral choices you can make on race day include wide brimmed hats, chewing on ice at aid stations, and just remembering to drink enough fluids. I’ve always raced by what I call “the golden rule”: the goal is to pee at least once every 56 miles on the bike. It’s obviously not a perfect rule, but as a rough guideline to make sure you’re hydrated out on course, it’s pretty useful.

While we’re talking about race day, it’s also useful to touch on cardiovascular drift. I’m sure you’ve all noticed it: while you’re on a long workout and holding a steady effort level, your HR slowly drifts upward. So what’s going on? There are a couple of theories, but a common theme is decreased stroke volume (i.e. the amount of blood your heart ejects with each beat).3 Higher degrees of cardiac drift are associated with a temporary drop in VO2 max and cardiac drift is more pronounced in hot environments.3 The beauty of it is that we can use cardiac drift on race day as a key for telling us how we’re managing pacing and hydration. If you see a very slow/steady amount of cardiac drift, you’re probably doing pretty well at managing the day. If you see a sharp increase in cardiac drift (or “heart rate decoupling” as it’s often called), then that’s a big red flag that you’re dehydrated and overheating. So while racing, you should always be looking at both pace and HR, and you should be aware of the relationship they have with each other early in the run. As the run progresses, keep an eye on how HR and pace are changing. If you see that HR climb at an increased rate at a given pace, you’d better slow down and get some fluids in ASAP, and then wait for your HR to get back under control, or else you could end up curled up in a ball on the side of the road.

At the end of the day, racing well in the heat is all about two opposite things: making yourself uncomfortable by exposing yourself to heat stress during training, and then doing everything possible to minimize heat stress on race day. Master those two arts, and you’ll have a nice leg up on the competition next time you race somewhere that humans probably shouldn’t be racing.

References

1) Periard, J.D; Eijsvogels, T.M.H; Daanen, H.A.M. Exercise Under Heat Stress: Thermoregulation, Hydration, Performance Implications, and Mitigation Strategies. Physiological Reviews, Apr 2021. Vol 101, pp 1873 – 1979

2) Walsberg GE. Consequences of skin color and fur properties for solar heat gain and ultraviolet irradiance in two mammals. J Comp Physiol B. 1988;158(2):213-21. doi: 10.1007/BF01075835. PMID: 3170827.

3) Wingo, Jonathan E.1; Ganio, Matthew S.2; Cureton, Kirk J.3. Cardiovascular Drift During Heat Stress: Implications for Exercise Prescription. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 40(2):p 88-94, April 2012. | DOI: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31824c43af

4) Otani, H., Kaya, M., Tamaki, A. et al. Effects of solar radiation on endurance exercise capacity in a hot environment. Eur J Appl Physiol 116, 769–779 (2016)

Start the discussion at slowtwitch.northend.network